Middle East and North Africa Unrest

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/792/mideast-north-africa-unrest.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, civilian protests and revolts have erupted as people’s frustrations with their conditions appear to have boiled over. At the end of 2010, 26 year old Tunisian fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in protest at his treatment by local authorities. The ensuing public outrage eventually ousted a 23-year old dictatorship. But this event was not limited to just Tunisia. It seems that event was the final spark that unleashed popular uprisings and frustrations throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

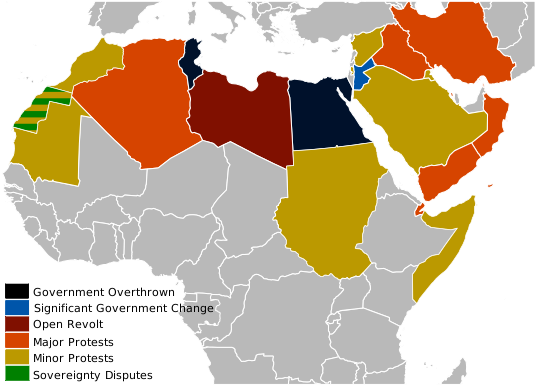

As of writing, protests have occurred in at least the following countries:

Others in the region, if they’ve been spared so far, will no doubt start to feel insecure as many rulers in the region are seen as illegitimate, corrupt or unwanted in some way.

On this page:

Why the uprisings now?

As explained in the Control of Resources page almost a decade earlier, the Middle East is riddled with authoritarian regimes of various kinds (monarchies, dictatorships, religious republics, etc). Most of these regimes have been given legitimacy through support by the outside world, e.g. the West, the former Soviet Union etc.

In some cases, potential proto-democracies emerging from a global wave of anti-colonialism were overthrown and replaced by dictators, while others were corrupted in various ways. Aid, in the form of military aid, or support in the form of foreign military bases ensured continued influence of outside superpowers while entrenching the illegitimate regimes.

Any descent has often been met by violence, crushing any potential for alternative voices. Or, as with Iran, overthrowing the brutal Shah regime has resulted in another repressive regime vehemently anti-West, anti-US in particular.

However, as I had written in that page above, Democracy or no democracy, people can and will only take so much. At some point, they will rise up and ask for their demands to be met.

If until now any protests against ruling regimes has generally been fruitless, what has changed?

Various potent issues have combined in different ways in recent weeks and months. Some of these can be generalized across the Middle East and North Africa, such as the global financial crisis, rising food prices, increasing unemployment, leaks of official documents (such as WikiLeaks of US embassy cables, the leak of how the Palestinian Authority had relented to Israel), ethnic/cultural divisions, and more.

But there are specific local issues that can be as important, if not more important some of these more general issues, or at least combine in different ways to make each uprising/protest unique while drawing from each other.

Decades of authoritarian rule has no doubt suppressed thoughts and opinions which are perhaps now bubbling to the surface when combined with all these other issues.

For many decades, some of these regimes were able to placate the vast majority of their populations via massive fossil fuel based revenues. Now, it seems, that is not enough.

Some of the Arab countries are also artificial; boundaries created by colonial powers to divide and conquer the Arab people also pitting clashing sub-cultures (e.g. Sunnis and Shiites) together, held together (or dominated by) an authoritarian power. But much of that may be unraveling in some nations.

Some of the protests focus on jobs, unemployment, corruption, etc (e.g. Egypt), while others focus on historical divisions (such as how Bahrain’s Shia majority has been ruled by a Sunni minority and royal family for decades).

All these local, regional and global issues therefore combine in various and potent ways ways, especially in the hands of the large population of unemployed but well-educated youth.

Some protests have been non-violent, while others have had varying degrees of violence, either by protestors or by security forces. Libyan security forces have been extremely violent, killing many, many protesters it appears. In Egypt many lives were also lost initially but eventually became much more non-violent as the military refused to attack protesters. In Oman, protests to date have been non-violent.

Following some unrest and protests in the country, Saudi Arabia recently banned all protests. It is one of the most extremist of regimes in the region, but enormously backed by the West. The authoritarian nature of Saudi rule is therefore accommodated and even supported by Western leaders (though despised by Western people in general). As the BBC recently reported, the ban announcement was accompanied by a 15% pay rise for state employees plus other benefits and funds for various groups — in effect, attempting to bribe or pacify the population, reducing their need to protest.

Stephen Zunes, Professor of Politics and Chair of Mid-Eastern Studies at the University of San Francisco, describes some other differences between protests in Tunisia/Egypt and Libya, including:

- Libya’s isolation from the West for decades (until recently) had entrenched Qaddafi somewhat whereas Egyptian and Tunisian dictatorships were dependent on the West’s support. This backing was always going to be easy to sway if, as happened, public opinion in the West sided with protesters in those countries

- Libyan elites have had

little to lose

by comparison and accordingly upped the violence level - More regionalism in Libya (though changing a lot lately indicating a genuine pro-democracy movement as with other regions)

- Some coordination despite any strong leadership in Egypt and Tunisia, whereas Libyan uprising appears more spontaneous with some pitched battles

Zune also details the West’s — and US in particular — relationship with Libya over the past few decades that Qaddafi has been in power, which is worth reading to get a bit more context that is typically omitted in mainstream media accounts.

More generally, Khaled Hroub, director of the Cambridge Arab Media Project, says that the recent strife across the Arab world reveals some salient messages:

- Arab peoples have had enough of their dictators — and of those who propped up these dictators

- The uprising debunks the rulers’ common cry that the sole conceivable alternative to them is an Islamist takeover

- The change heralded by these revolutions is inspired and made directly by the people giving Arabs confidence that their fate is finally in their own hands

- The widespread Arab protest is fundamentally political; wanting fundamental change not just surface or short-term ones

- (Superficial) stability based on armed security is no longer an option.

The west’s short-sighted strategy of buying stability while turning a blind eye to repression reveals the hollowness of its democratic values.

- In face of massive unarmed determination, and under the world’s vigilant scrutiny (through the globalization of media and use of various Internet tools, for example), the security apparatuses and the regimes they protect are unmasked as paper tigers.

As an interesting aside, former US President Bush’s project to supposedly bring democracy to Iraq through external invasion and military force has been disastrous. At the time of the Iraq war build up, thousands of voices were raised that enforced democracy from outside cannot work. Instead, the recent uprisings and protests throughout the Middle East strengthens that point; more was achieved in the few weeks of Egyptian protests with far less of a death toll or national destruction. Though of course there is much still to be seen.

A social media revolution?

Some have described uprisings such as the one in Egypt as a Facebook revolution or Twitter revolution, referring to the social media web sites that facilitate much easier information sharing and more.

Such tools have been enablers for underlying social, political and economic issues have always been there. Unlike technologies before it, the Internet has tremendously increased the speed at which people can communicate and relay compelling information around the world to by-pass official censorship, which has trouble keeping up.

It is not perfect: the Egyptian state was able to force various companies to turn off their services at short notice, showing how centralized/corporatized the (publicly) created Internet has now become. Even the US has been mulling authoritative powers on the Internet that some feel goes against what it officially stands for.

An awakened educated youth

An additional key factor in the eruption of revolt is the sheer number of disaffected youth, as these are also the Internet generation

using those social media tools effectively.

The young population in the Middle East region is large — as is the percentage of young who are unemployed but well-educated, meaning there is a lot of potential political energy that can be channeled towards protest and change.

Although there are some images of young protesters hurling rocks at security forces, the overwhelming (and inappropriate) force has typically been from government security forces.

It is to the credit of many young people that they have channeled their energy towards democratic political change, often non-violently (recall all the pictures from Egypt on how they self-organized to check bags of other protesters to ensure no weapons etc were being brought into the main square, or how they encouraged each other to clean up the streets afterwards.)

Media, information management, propaganda

Also, we cannot forget the propaganda the accompanies these kinds of events. We remember during the first Gulf War, how a US public relations company used propaganda to present a Kuwaiti ambassador’s 15-year old daughter to US Congress to pretend she was a nurse and lament at Iraqi soldiers killing babies — all to help strengthen Western support for a military invasion. It was all made up of course, but it served its purpose — to gain public and political support for a war.

Since that time, information technology has moved on. Whether such crude propaganda still goes on during what we see on our televisions and read in the media, is hard to of course know until it might be too late. However, through the proliferation of the Internet and mobile communications crude propaganda has the potential to be more easily foiled and disproved (though governments are keen to figure out ways to disable these in times of emergency

as we saw in Egypt or use them to their own advantage.)

When we see people rising up against autocratic regimes, it is almost instinctive to support the opposition. Yet, while we see many protestors interviewed on television or read their reports on the Internet, the nature of the conflicts makes it hard to know if those opposing views are truly representative of national sentiment because many agendas can all come together with differing ideologies but common goals such as toppling the incumbent regime.

For example, around the world as well as inside Libya, protestors are replacing the official Libyan flag with the previous flag of the monarchy. Does this hint that some elements of the protests are backed by a monarchist agenda (risking the replacement one non-democratic regime for another) or was it just a symbolic gesture of sorts? It seems it is likely symbolic, but the aftermath will be played out over a longer time frame.

An example from an earlier time is Iran - when the Shah was overthrown many, including women, supported the opposition for the appeared to stand up to oppression. However, what was not realized at the time was that the incoming Islamic clergy would be as conservative and controversial as it turned out to be.

Some propaganda can be very sophisticated as the build up to the Iraq invasion in 2003 showed. Various global campaigns involving public relations firms and colluding governments actively tried to convince skeptical populations about the need to invade Iraq.

Other propaganda can be seen as quite crude and even ridiculous. For example, late into the evening of February 20, 2011, Libya claimed that many

of the protesters were on drugs, and even later claimed that it supplied by Al Qaeda (probably trying to raise a fear of terrorism and his fight against it which the West has appreciated in recent years).

The Libyan government’s brutality seems to be backfiring. It seems more desperate in its claims and so it tried to raise fears to try and control the situation. With numerous ambassadors and others resigning from their posts and with some military units refusing orders to shoot on civilians, the Libyan regime looks to be on its last legs, albeit determined to go out only with a bloody fight (and blame the bloodshed on others). Al Jazeera and others are banned from Libya (and some other Middle East countries) supposedly so it can impose its own propaganda (which has been very poor to date).

West looks on

The West has long had an interest in the region. But is its view of the region still dominated by a combination of Cold War and overly simplistic War on Terror related ideas?

During the Cold War, the West (and Soviet Union) actively tolerated, even encouraged, authoritarian regimes for various geopolitical reasons (for example, Iran’s brutal dictatorial regime governed by the Shah was friendly to the West. It was overthrown by a religiously extreme and anti-US regime and so the US supported Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and encouraged a brutal near decade-long war against Iran. It was also at this time that Saddam Hussein’s worst atrocities took place. Only when Saddam Hussein over-stepped his bounds and invaded Kuwait did he turn into a public enemy).

Might Western countries fear their puppet regimes may be replaced by less pliable regimes? In that context, it would not be too surprising to hear these nations raising the fear that the autocratic regimes may be replaced by Islamic extremist regimes, perhaps as a pretext for more involvement in the region.

But an awakened and aware population in the Middle East might make this more difficult than in the past, even though this sort of action for decades has barely been acknowledged in the mainstream — at least not in a substantive, self-critical way:

[The West’s] interventions in the region have historically tended to support exactly those autocrats whose power is now being challenged, while promoting neo-liberal economic policies that have enriched the minority elites while making daily life more difficult for many in the region.

It is not good enough to talk, as Clinton, Barack Obama, William Hague and others have done, in feeble generalities about

stability,freedomandrestraintin a networked world where the weakness and slowness of expression of those sentiments is so rapidly exposed.If western diplomacy — and media commentary — has a function in these times, it should be to expose and focus on the precise dynamics of the awful inequalities in these societies and the routine violence and oppression that sustains them.

If the west has a contribution to make, it is in an honest and accurate audit of the nature of the states our governments have for so long been supporting, not prevarication. To describe reality, not vague ideals, and in describing it, reboot the policies that have for so long supported repression and corruption.

The West’s interests in the region are of course well known: oil/fossil fuels mostly. Even where a specific country may not have significant oil resources itself, their neighbors, or neighbor’s neighbors may do, so stability

for the West means secured energy access.

As Noam Chomsky charges, the US and its allies would want to prevent democracy in the Arab world because the region would be less susceptible to Western influence:

The U.S. and Its Allies Will Do Anything to Prevent Democracy in the Arab World, Democracy Now, May 11, 2011

Turmoil in places like Libya has already caused stock markets to shudder, and oil prices to rise, leading to even more protests domestically following the global financial crisis and the resulting structural adjustment programs within countries that once imposed it on others to devastating effect.

Reliance on foreign sources of non-renewable energy resources is discussed further on this site’s energy security section.

Another interest the West has in the region is military: not just geopolitically as alluded to above, but also selling vast amounts of arms and/or military training. Some of this is justified as improving relations (and the message in the past decade or more has also been about improving cooperation and encouraging democracy, though that has hardly been the intent).

Between 2002 and 2009, for example, of the top 10 developing country arms sales recipients,

- Saudi Arabia tops the list at just under $40 billion dollars worth of arms sales (14% of the total sold to developing countries)

- UAE comes third at $17.3bn (6%)

- Egypt fourth at $13.9bn (5%)

- Iraq 10th at $8.1bn (3%)

The United States was the principle supplier in this period accounting for roughly half of all sales to the region, with major Western European powers accounting for around 25%, the rest made up by Russia (10%), China (3%), and other European nations. These numbers are approximate. More details can be seen on this site’s arms sales section.

However, military sales to autocratic regimes primarily keeps those regimes entrenched for as long as possible which may overlap with the West’s geopolitical interests, but it also boosts revenues to the arms sellers whose governments act as glorified sales people. Of course, criticism of this results in fear-mongering and propaganda by arms sellers that jobs will be lost and that these industries are important. (Are jobs that prop up dictators and autocratic regimes productive and ethical — even though they count to GDP? Even when the selling nations’ population in general may not desire such actions, the military industrial complex is very influential and resourceful in getting their viewpoint across to the policy makers.)

It should be noted that British media, Al Jazeera and others have shown protesters holding tear gas canisters retrieved after government security forces in places like Egypt have used them, showing some sort of made-in-the-West label, such as in UK. The Guardian notes, for example, that UK has sold tear gas and riot gear to Libya whose crackdown on protesters has been incredibly brutal.

In the above video clip — from a political comedy show in the UK (sometimes only comedy can highlight how absurd some serious policies are!) — note is made of how various British leaders have accommodated dictators and autocrats in the Middle East, for example, Thatcher and Mubarak, Blair and Qaddafi, and Brown and King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia.

The clip also notes a UK Department of Trade and Industry document, Investing in Libya

from 2010 noting that Change is in the air in Libya. … Not just political change, but clear business opportunity for those patient, persistent and determined enough to take it.

Admittedly the West also treads a fine line: any visible Western backing of opposition regimes will make the current regime feel it can legitimately crack down on the opposition, citing Western/external influence etc. Any increasing turmoil may still force fossil fuel prices up anyway leading to more domestic problems for Western governments given the effects of the global financial crisis and rising costs of living and high unemployment.

Yet, might this turmoil help accelerate the demand for alternative energy which would allow Western governments to reduce or eliminate their support for illegitimate regimes in the long run?

East looks on

It is not just the West that will have an interest in the region; the emerging nations in Asia, and other parts of the developing world will also be looking on. India and China for example are hungry for more energy given their growing economies. Any problems in the Middle East is likley to have effects in Asia and around the world.

The global inter-dependency that so many desire also requires global stability which support of authoritarian regimes cannot bring in the long term.

Central Asian despots may have cause to worry too. Even China may have cause to worry internally from all this; encouraged by the protests in the Middle East, it seems an Internet-based approach to create a Jasmine Revolution

protest has got the authorities worried.

An African-wide Protest

Many of the countries typically highlighted so far are Middle East but also North African. A lot of mainstream media reports frame this as a Middle East protest, which it is. But that does not mean it is not also a part of growing unrest and protest around Africa, either. Mainstream media has barely paid detailed attention to other protests around Sub-Saharan Africa in recent months like it has to North Africa and the Middle East.

As Firoze Manji, the editor of Pambazuka Online, an advocacy website for social justice in Africa, summarizes, there have been protests and unrest (or unrest brewing) in various Sub-Saharan African nations such as:

- Gabon

- Sudan

- Ethiopia

- Cameroon

- South Africa

- Madagascar

- Mozambique

- Senegal

Not all of these are revolution-oriented or to the same scale, admittedly. Many are related to rising food prices and increasing economic hardship, which Manji also notes is inter-related with the North African experience and an even wider global issue:

[Manji] argues that globalization and the accompanying economic liberalization has created circumstances in which the people of the global South share very similar experiences.

These include

[i]ncreasing pauperization, growing unemployment, declining power to hold their governments to account, declining income from agricultural production, increasing accumulation by dispossession — something that is growing on a vast scale — and increasing willingness of governments to comply with the political and economic wishes of the North,Manji explains.

A Global Neoliberal/corporate Globalization-related Protest

Many of these protests can also be seen in the context of a decade or more of neoliberal globalization, seen as corporate friendly but in a way that has undermined many people’s ability to hold their own governments to account, while governments also find themselves constrained in policy space (even when they want to do good for their people!).

Although the Protests Around the World page on this site was started many years ago and has not been updated for a number of years now, the protests there describe how a neo-liberal form of globalization, and related financial crises at the time primarily affected developing nations negatively. The global South’s response was to follow an IMF-led prescription of harsh Structural Adjustment policies that has caused so many hardships.

These protests were barely reported in the Western mainstream media, thus making it easy to criticize opposition to these policies (at a time where those same policies were benefiting the West so much).

The financial crisis this time round has primarily affected industrialized countries. The harsh structural adjustments have now been applied to many rich nations too, much to the understandable anger of many ordinary citizens. The general public stands to lose out a lot, while bankers and others — seen as the primary cause of this particular crisis — appear to be less affected and are even given large bonuses in times of cut backs, with what is seen as public bail out money.

Some of the financial speculation that caused this problem has shifted away towards commodity and food speculation exacerbating poor harvests into another food crisis. This increasing hunger, combined with the impact climate change seems to be having on harvests, as well as increasing unemployment and governments finding the financial crisis affecting them, have all contributed to unrest, not just in the Middle East (where it is perhaps quite prominent due to the sheer number of autocratic regimes), but around the world. As Raj Patel writes, these are all combining to become revolution’s kindling.

A critical time in world history

Most of this is conjecture, what ifs, etc. No-one can predict the future or foresee how the influence of new political power from nations such such as China, India and Brazil will play out in this context. Yet, it certainly feels like a critical time in world history.

More Information

These events are so momentous that this page unfortunately omits many, many details and contains many generalizations. For more detailed coverage, consider these:

- This web site’s news stories (from Inter Press Service) on

- Inter Press Service

- Al Jazeera

- Arab and Middle East Protests news coverage from the Guardian, UK

- Mid-East and Arab Unrest coverage from the BBC

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues