World Military Spending

Author and Page information

This print version has been auto-generated from https://www.globalissues.org/article/75/world-military-spending

Of all the enemies to public liberty war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes … known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few.… No nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare.

On this page:

World Military Spending

Global military expenditure stands at over $1.7 trillion in annual expenditure at current prices for 2012. It fell by around half a percent compared to 2011 — the first fall since 1998.

(1991 figures are unavailable. Chart uses 2011 constant prices for comparison.)

Summarizing some key details from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s Year Book 2013 summary on military expenditure1:

- World military expenditure in 2012 is estimated to have reached $1.756 trillion;

- This is a 0.4 per cent decrease in real terms than in 2011 — the first fall since 1998;

- The total is still higher than in any year between the end of World War II and 2010;

- This corresponds to 2.5 per cent of world gross domestic product (GDP), or approximately $249 for each person in the world;

The USA with its massive spending budget, has long been the principal determinant of the current world trend, often accounting for close to half of all the world’s military expenditure. The effects of global financial crisis2 and the post-Iraq/Afghanistan military operations have seen a decline in its spending, now accounting for 39% of spending in 2012.

SIPRI has commented in the past on the increasing concentration of military expenditure, i.e. that a small number of countries spend the largest sums. This trend carries on into 2012 spending. For example,

- The 15 countries with the highest spending account for over 81% of the total;

- The USA is responsible for 39 per cent of the world total, distantly followed by the China (9.5% of world share), Russia (5.2%), UK (3.5%) and Japan (3.4%)

Military spending is concentrated in North America, Europe, and increasingly, Asia:

But as recent figures have shown, there is a shift in expenditure — from austerity-hit Western Europe and reduced spending by the US, to increased spending in Eastern Europe and Asia.

Increased spending before and even during global economic crisis

The global financial and economic crisis3 resulted in many nations cutting back on all sorts of public spending, and yet military spending continued to increase. Only in 2012 was a fall in world military expenditure noted — and it was a small fall. How would continued spending be justified in such an era?

Before the crisis hit, many nations were enjoying either high economic growth or far easier access to credit without any knowledge of what was to come.

A combination of factors explained increased military spending in recent years before the economic crisis as earlier SIPRI reports had also noted, for example:

- Foreign policy objectives

- Real or perceived threats

- Armed conflict and policies to contribute to multilateral peacekeeping operations

- Availability of economic resources

The last point refers to rapidly developing nations like China and India that have seen their economies boom in recent years. In addition, high and rising world market prices for minerals and fossil fuels (at least until recently) have also enabled some nations to spend more on their militaries.

China, for the first time, ranked number 2 in spending in 2008.

But even in the aftermath of the financial crisis amidst cries for government cut backs, military spending appeared to have been spared. For example,

The USA led the rise [in military spending], but it was not alone. Of those countries for which data was available, 65% increased their military spending in real terms in 2009. The increase was particularly pronounced among larger economies, both developing and developed: 16 of the 19 states in the G20 saw real-terms increases in military spending in 2009.

For many in Western Europe or USA at the height of the financial crisis, it may have been easy to forget the global

financial crisis, was primarily a Western financial crisis (albeit with global reverberations). So this helps explains partly why military spending did not fall as immediately as one might otherwise think. As SIPRI explains:

- Some nations like China and India have not experienced a downturn, but instead enjoyed economic growth

- Most developed (and some larger developing) countries have boosted public spending to tackle the recession using large economic stimulus packages. Military spending, though not a large part of it, has been part of that general public expenditure attention (some also call this

Military Keynesianism

- Geopolitics and strategic interests are still factors to project or maintain power:

rising military spending for the USA, as the only superpower, and for other major or intermediate powers, such as Brazil, China, Russia and India, appears to represent a strategic choice in their long-term quest for global and regional influence; one that they may be loath to go without, even in hard economic times

, SIPRI adds.

For USA’s 2012 military expenditure, for example, although there is fall, it is primarily related to war-spending (Iraq and Afghanistan operations primarily). But the baseline defense budget, by comparison, is largely similar to other years (marking a reduction in the rate of increased spending).

By contrast, when it comes to smaller countries — with no such power ambitions and, more importantly, lacking the resources and credit-worthiness to sustain such large budget deficits — many have cut back their military spending in 2009, especially in Central and Eastern Europe.

(Perlo-Freeman, Ismail and Solmirano, pp.1 – 2)

Natural resources have also driven military spending and arms imports in the developing world. The increase in oil prices means more for oil exporting nations.

The natural resource curse

has long been recognized as a phenomenon whereby nations, despite abundant rich resources, find themselves in conflict and tension due to the power struggles that those resources bring (internal and external influences are all part of this).

In their earlier 2006 report5 SIPRI noted that, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Russia and Saudi Arabia have been able to increase spending because of increased oil and gas revenues, while Chile and Peru’s increases are resource-driven, because their military spending is linked by law to profits from the exploitation of key natural resources.

Also, China and India, the world’s two emerging economic powers, are demonstrating a sustained increase in their military expenditure and contribute to the growth in world military spending. In absolute terms their current spending is only a fraction of the USA’s. Their increases are largely commensurate with their economic growth.

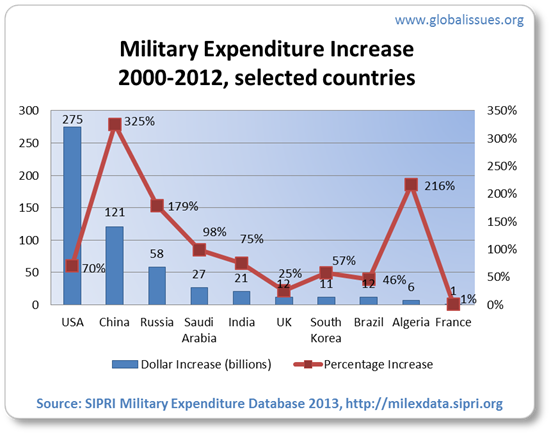

The military expenditure database6 from SIPRI also shows that while percentage increases over the previous decade may be large for some nations, their overall spending amounts may be varied.

(See also this summary of recent trends7, also from SIPRI. The latest figures SIPRI uses are from 2012, and where necessary (e.g. China and Russia), include estimates.)

Spending for peace vs spending for war

In a similar report from 20048, the SIPRI authors also noted that, There is a large gap between what countries are prepared to allocate for military means to provide security and maintain their global and regional power status, on the one hand, and to alleviate poverty and promote economic development, on the other.

Indeed, compare the military spending with the entire budget of the United Nations:

The United Nations and all its agencies and funds spend about $30 billion each year, or about $4 for each of the world’s inhabitants. This is a very small sum compared to most government budgets and it is less than three percent of the world’s military spending. Yet for nearly two decades, the UN has faced financial difficulties and it has been forced to cut back on important programs in all areas, even as new mandates have arisen. Many member states have not paid their full dues and have cut their donations to the UN’s voluntary funds. As of December 31, 2010, members’ arrears to the Regular Budget topped $348 million, of which the US owed 80%.

The UN was created after World War II with leading efforts by the United States and key allies.

- The UN was set up to be committed to preserving peace through international cooperation and collective security10.

- Yet, the UN’s entire budget is just a tiny fraction of the world’s military expenditure, approximately 1.8%

- While the UN is not perfect and has many internal issues that need addressing11, it is revealing that the world can spend so much on their military but contribute so little to the goals of global security, international cooperation and peace.

- As well as the above links, for more about the United Nations, see the following:

At the current level of spending, it would take just a handful of years for the world’s donor countries to cover their entire aid shortfall, of over $4 trillion in promised official aid since 197014, 40 years ago.

Unfortunately, however, as the BBC notes, poverty fuels violence and defense spending has a tendency to rise during times of economic hardship. The global financial crisis15 is potentially ushering in enormous economic hardship around the world.

At a time when a deep economic recession is causing much turbulence in the civilian world … defense giants such as Boeing and EADS, or Finmeccanica and Northrop Grumman, are enjoying a reliable and growing revenue stream from countries eager to increase their military might.

Both geopolitical hostilities and domestic violence tend to flare up during downturns.

…

Shareholders and employees in the aerospace and defense industry are clearly the ones who benefit most from growing defense spending.

Defense companies, whose main task is to aid governments’ efforts to defend or acquire territory, routinely highlight their capacity to contribute to economic growth and to provide employment.

Indeed, some $2.4 trillion (£1.5tr), or 4.4%, of the global economy

is dependent on violence, according to the Global Peace Index, referring toindustries that create or manage violence— or the defense industry.…

Military might delivers geopolitical supremacy, but peace delivers economic prosperity and stability.

And that, the report insists, is what is good for business.

The Global Peace Index17 that the BBC is referring to is an attempt to quantify the difficult-to-define value of peace and rank countries based on over 20 indicators using both quantitative data and qualitative scores from a range of sources. Here is a summary chart from their latest report:

Their introductory video also notes that peace isn’t just the absence of weapons; it is the result of an approach to development in general:

(The top ranking nations on the global peace index were, Iceland, Denmark, New Zealand, Austria, Switzerland, Japan, Finland, Canada, Sweden and Belgium. It is worth looking at the report for the full list of indicators used, which cover a mixture of internal and external factors, weighted in various ways.)

US Military Spending

The United States has unquestionably been the most formidable military power in recent years. Its spending levels, as noted earlier, is the principle determinant of world military spending and is therefore worth looking at further.

Generally, US military spending has been on the rise. Recent increases are attributed to the so-called War on Terror and the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions, but it had also been rising before that.

For example, Christopher Hellman, an expert on military budget analysis notes in The Runaway Military Budget: An Analysis23, (Friends Committee on National Legislation, March 2006, no. 705, p. 3) that military spending had been rising since at least 1998, if not earlier.

The US Department of Defense provides a breakdown of military spending since 2001:

Overall spending

Defense budget vs War spending

Raw data and sources

| Year | National defense budget ($bn) | War Supplemental($bn) | Other | Total military spending ($bn) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Source: Growth in U.S. Defense Spending Since 2001 24, US Department of Defense FY2014 Budget Request, April 2013. Note: Numbers may not add up due to rounding. Figures include Department of Defense spending (which includes non-war supplemental appropriations for some years) and the costs of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Department of Energy’s nuclear weapons program are not included and typically range from $21bn – $25bn each year. FY14 figure is the requested budget. Other includes non-war supplemental appropriations, e.g. funding needed in base budget for fuel costs, hurricane relief, and other disaster relief. Laicie Olson from the Center for Arms Control provides further information and analysis25. | ||||

| 2014 | 527 | 88 | 615 | |

| 2013 | 528 | 87 | 0.1 | 615 |

| 2012 | 530 | 115 | 645 | |

| 2011 | 528 | 159 | 687 | |

| 2010 | 528 | 162 | 1 | 691 |

| 2009 | 513 | 146 | 7 | 666 |

| 2008 | 479 | 187 | 666 | |

| 2007 | 431 | 166 | 3 | 601 |

| 2006 | 411 | 116 | 8 | 535 |

| 2005 | 400 | 76 | 3 | 479 |

| 2004 | 377 | 91 | 0.3 | 468 |

| 2003 | 365 | 73 | 438 | |

| 2002 | 328 | 17 | 345 | |

| 2001 | 287 | 23 | 6 | 316 |

The decline seen in later years was initially mostly due to Iraq war reduction and redeployment to Afghanistan, followed by an attempt to scale down Afghanistan operations, too. The baseline budget, however, showed continued increase until only recently, albeit at a seemingly lower rate. In addition, the effects of the global financial crisis26 has started to be felt now.

Why are the numbers quoted above for US spending so much higher than what has been announced as the budget for the Department of Defense?

Unfortunately, the budget numbers can be a bit confusing. For example, the Fiscal Year budget requests for US military spending do not include combat figures (which are supplemental requests that Congress approves separately). The budget for nuclear weapons falls under the Department of Energy, and for the 2010 request, was about $25 billion.

The cost of war (Iraq and Afghanistan) has been very significant during George Bush’s presidency. Christopher Hellman and Travis Sharp also discuss the US fiscal year 2009 Pentagon spending request27 and note that Congress has already approved nearly $700 billion in supplemental funding for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and an additional $126 billion in FY'08 war funding is still pending before the House and Senate.

Furthermore, other costs such as care for veterans, health care, military training/aid, secret operations, may fall under other departments or be counted separately.

The frustration of confusing numbers seemed to hit a raw nerve for the Center for Defense Information, concluding

The articles that newspapers all over the country publish today will be filled with [military spending] numbers to the first decimal point; they will seem precise. Few of them will be accurate; many will be incomplete, some will be both. Worse, few of us will be able to tell what numbers are too high, which are too low, and which are so riddled with gimmicks to make them lose real meaning.

Nonetheless, compared to the rest of the world, these numbers have long been described as staggering.

In Context: US Military Spending Versus Rest of the World

Using the SIPRI military expenditure database29 we see the breakdown described earlier:

As a pie chart

The US alone accounts for over two-fifths (or just under half) of the world’s spending:

Since 2001

World spending has risen since 2001. Both the US and other top spenders have influenced that rise.

US vs. others

- US military spending accounts for 39 percent, or almost two-fifths of the world’s total military spending

- US military spending is almost 4 times more than China, almost 8 times more than Russia, and about 70 times more than Iran.

- US military spending is some 54 times the spending of Cuba, Iran, and Syria) whose spending amounts to around $12-13 billion, which is mostly Iran

- US spending is almost as much as than the next top 11 countries.

- The United States and its strongest allies (the NATO countries, Japan, South Korea and Australia) spend something in the region of $1.2 trillion on their militaries combined, representing over 70 percent of the world’s total.

- The Iran, Syria, Russia, and China together account for about $260 billion or 39% of the US military budget.

Top spenders (and sources)

| Country | Dollars (billions) | % of total | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

Source: The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2012 30, SIPRI, 2013 Note: Due to rounding, some percentages may be slightly off. If you are viewing this table on another site, please see http://www.globalissues.org/article/75/world-military-spending31 for further details. | |||

| United States | 711 | 39.0% | 1 |

| China | 166 | 9.5% | 2 |

| Russia | 91 | 5.2% | 3 |

| United Kingdom | 61 | 3.5% | 4 |

| Japan | 59 | 3.4% | 5 |

| France | 59 | 3.4% | 6 |

| Saudi Arabia | 57 | 3.2% | 7 |

| India | 46 | 2.6% | 8 |

| Germany | 46 | 2.6% | 9 |

| Italy | 34 | 1.9% | 10 |

| Brazil | 33 | 1.9% | 11 |

| South Korea | 32 | 1.8% | 12 |

| Australia | 9 | 1.5% | 13 |

| Canada | 23 | 1.3% | 14 |

| Turkey | 18 | 1.0% | 15 |

| Rest of world | 321 | 18.2% | |

| Global Total (not all countries shown): 1,753 | |||

Commenting on the earlier data, Chris Hellman noted that when adjusted for inflation the request for 2007 together with that needed for nuclear weapons the 2007 spending request exceeds the average amount spent by the Pentagon during the Cold War, for a military that is one-third smaller than it was just over a decade ago.32

Generally, compared to Cold War levels, the amount of military spending and expenditure in most nations has been reduced. For example, global military spending declined from $1.2 trillion in 1985 to $809 billion in 1998, though since 2005 has risen to over $1 trillion again. The United States’ spending, up to 2009 requests may have be reduced compared to the Cold War era but is still close to Cold War levels33.

In Context: US military budget vs. other US priorities

Supporters of America’s high military expenditure often argue that using raw dollars is not a fair measure, but that instead it should be per capita or as percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and even then the spending numbers miss out the fact that US provides global stability with its high spending and allows other nations to avoid such high spending.

Although some of the issues discussed here are about US spending, they are also relevant to a number of other nations.

Should spending be tied to GDP?

Chris Hellman argues that GDP is not an appropriate way to measure necessary US military budget allocation:

Linking military spending to the GDP is an argument frequently made by supporters of higher military budgets. Comparing military spending (or any other spending for that matter) to the GDP tells you how large a burden such spending puts on the US economy, but it tells you nothing about the burden a $440 billion military budget puts on U.S. taxpayers. Our economy may be able to bear higher military spending, but the question today is whether current military spending levels are necessary and whether these funds are going towards the proper priorities. Further, such comparisons are only made when the economy is healthy. It is unlikely that those arguing that military spending should be a certain portion of GDP would continue to make this case if the economy suddenly weakened, thus requiring dramatic cuts in the military.

Since Hellman wrote the above, there has of course been the global financial crisis35, that started from the US and has spread. Hellman might be surprised to find that even in such times, there are still serious proposals for pegging military spending to GDP. In recent months some senators and representatives have introduced proposals and bills calling for 4% of GDP to be guaranteed as the military budget (not including supplementals

for war).

As Travis Sharp summarizes, critics of tying the US military budget to 4% of GDP fail in 3 ways:

- It would add $1.4 trillion to $1.7 trillion to deficits over the next decade and provide more defense funding than is forecast to be necessary;

- It would determine budgets using rigid formulas instead of realistic threat-based analysis, which would allow procurement to drive strategy rather than the other way around; and

- It is politically unviable in the economic and budgetary environment faced by the United States.

Sharp also adds that when the war supplemental for Iraq and Afghanistan are considered, the US budget is already over the 4% mark. The other concerns is that tying it to GDP eases the debate that would otherwise occur on the issue:

GDP is an important metric for determining how much the United States could afford to spend on defense, but it provides no insight into how much the United States should spend. Defense planning is a matter of matching limited resources to achieve carefully scrutinized and prioritized objectives. When there are more threats, a nation spends more. When there are fewer threats, it spends less. As threats evolve, funding should evolve along with them.…

Unfortunately, setting defense spending at four percent of GDP would shield the Pentagon from careful scrutiny and curtail a much-needed transparent national debate.

(See also the Tying U.S. Defense Spending to GDP: Bad Logic, Bad Policy37, (April 15, 2008) from Travis Sharp for additional details.)

With the change in presidency from George Bush to Barack Obama, the US has signaled a desire to reform future spending and already indicated significant changes for the FY 2010 defense budget38. For example, the US has indicated that it will cut some high-tech weapons that are deemed as unnecessary or wasteful, and spend more on troops and reform contracting practices and improve support for personnel, families and veterans.

There is predictable opposition from some quarters arguing it will threaten jobs and weaken national security, even though spending has been far more than necessary for over a decade. The Friends Committee on National Legislation argues that the job loss from decreased military spending argument is weak39: It is true that discontinuing weapons systems will cause job loss in the short term, but unnecessary weapons manufacturing should not be considered a jobs program (that would be like spending billions of dollars digging holes), and research shows that these jobs can be successfully transferred to other sectors.

In other words, this is unnecessary and wasted labor (as well as wasted capital and wasted resources).

Furthermore, rather than creating/sustaining jobs, some research suggests that increased military spending leads to job losses40.

And well into 2010, SIPRI comments on the sustained high US military spending despite Obama’s suggestion otherwise:

How is it that US military spending, already far exceeding that of any other country and at record real-terms levels since World War II, is continuing to increase in the face of a dire economic crisis and a president committed to a more multilateral foreign policy approach?

One factor remains the conflict in Afghanistan, to which Obama is committed and where the US troop presence is increasing, even as the conflict in Iraq winds down.

Another is that reducing the military budget can be like turning round the proverbial supertanker—weapon programs have long lead times, and may be hard to cancel. Members of the Congress may also be resistant to terminating programmes bringing jobs to their states….

However, the fact that military expenditure is continuing to increase even as other areas are cut suggests a clear strategic choice: the fundamental goal of ensuring continued US dominance across the spectrum of military capabilities, for both conventional and ‘asymmetric’ warfare, has not changed.

US high military spending means others do not have to?

Some argue that high US military spending allows other nations to spend less. But this view seems to change the order of historical events:

- During the Cold War, high spending was common around the world.

- High spending was reduced by allies such as various European and Asian countries as the Cold War ended (almost 2 decades ago) not because other nations felt they would be protected by the US — a dangerous foreign policy choice by any sovereign nation to rely so much on others in this way — but because they perceived any global threat from the Cold War had diminished and simply didn’t need such high spending any more; globalization of trade was supposed to be ushered in and lead to a new era.

- It was only the US as the remaining global super power that maintained a high budget. Many argue this was to strengthen its position as sole super power and that its

military industrial complex

was able to convince their public to maintain it.

Past empires have throughout history have justified their position as being good for the world. The US is no exception.

However, whether this global hegemony and stability actually means positive stability, peace and prosperity for the entire world (or most of it) is subjective. That is, certainly the hegemony at the time, and its allies would benefit from the stability, relative peace and prosperity for themselves, but often ignored in this is whether the policies pursued for their advantages breeds contempt elsewhere.

As the global peace index chart shown earlier reveals, massive military spending has not led to a much global peace.

As noted in other parts of this site, unfortunately more powerful countries have also pursued policies that have contributed to more poverty, and at times even overthrown fledgling democracies in favor of dictatorships or more malleable democracies42. (Osama Bin Laden, for example, was part of an enormous Islamic militancy encouraged and trained by the US to help fight the Soviet Union. Of course, these extremists are all too happy to take credit for fighting off the Soviets in Afghanistan, never acknowledging that it would have been impossible without their so-called great satan

friend-turned-enemy!)

So the global good hegemon theory may help justify high spending and even stability for a number of other countries, but it does not necessarily apply to the whole world. To be fair, this criticism can also be a bit simplistic especially if an empire finds itself against a competitor with similar ambitions, that risks polarizing the world, and answers are likely difficult to find.

But even for the large US economy, the high military spending may not be sustainable in the long term. Noting trends in military spending, SIPRI added that the massive increase in US military spending has been one of the factors contributing to the deterioration of the US economy since 200143. SIPRI continues that, In addition to its direct impact of high military expenditure, there are also indirect and more long-term effects. According to one study taking these factors into account, the overall past and future costs until year 2016 to the USA for the war in Iraq have been estimated to $2.267 trillion.

US military budget vs. other US priorities

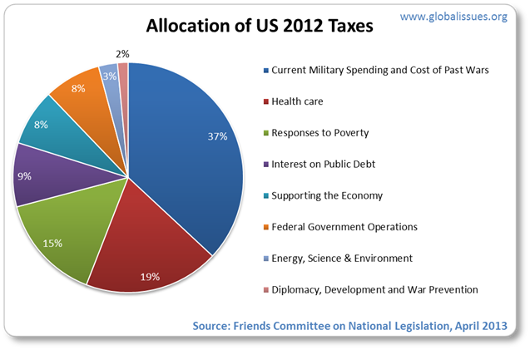

The peace lobby, the Friends Committee on National Legislation, calculates for Fiscal Year 2012 that the majority of US tax payer’s money goes towards war:

As a pie chart

Raw data and sources

| 2012 (in billions of dollars) | 2012 percent of federal funds budget | |

|---|---|---|

Source: Where Do Our Income Tax Dollars Go?44, Friends Committee on National Legislation, February 2013. Note, due to rounding, totals and percentages may not add up. Current military spending includes Pentagon budget, nuclear weapons and military-related programs throughout the budget. | ||

| Current Military Spending | 806 | 27% |

| Interest on Pentagon Debt | 188 | 6% |

| Costs of past wars | 129 | 4% |

| Total military percent | 1,123 | 37% |

| Health care | 558 | 19% |

| Responses to Poverty | 452 | 15% |

| Interest on Public Debt | 263 | 9% |

| Supporting the Economy | 241 | 8% |

| Federal Government Operations | 258 | 8% |

| Energy, Science, & Environment | 81 | 3% |

| Diplomacy, Development and War Prevention | 45 | 2% |

Furthermore, national defense

category of federal spending is typically just over half of the United States discretionary budget (the money the President/Administration and Congress have direct control over, and must decide and act to spend each year. This is different to mandatory spending, the money that is spent in compliance with existing laws, such as social security benefits, medicare, paying the interest on the national debt and so on). For recent years here is how military, education and health budgets (the top 3) have fared:

| Year | Total ($) | Defense ($) | Defense (%) | Education ($) | Education (%) | Health ($) | Health (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sources and notes

| |||||||

| 200945 | 997 | 541 | 54 | 61.9 | 6.2 | 52.7 | 5.3 |

| 200846 | 930 | 481.4 | 51.8 | 58.6 | 6.3 | 52.3 | 5.6 |

| 200747 | 873 | 460 | 52.7 | 56.8 | 6.5 | 53.1 | 6.1 |

| 200648 | 840.5 | 438.8 | 52 | 58.4 | 6.9 | 51 | 6.1 |

| 200549 | 820 | 421 | 51 | 60 | 7 | 51 | 6.2 |

| 200450 | 782 | 399 | 51 | 55 | 7 | 49 | 6.3 |

| 200351 | 767 | 396 | 51.6 | 52 | 6.8 | 49 | 6.4 |

For those hoping the world can decrease its military spending, SIPRI warns that while the invasion [of Iraq] may have served as warning to other states with weapons of mass destruction, it could have the reverse effect in that some states may see an increase in arsenals as the only way to prevent a forced regime change52.

In this new era, traditional military threats to the USA are fairly remote. All of their enemies, former enemies and even allies do not pose a military threat53 to the United States. For a while now, critics of large military spending have pointed out that most likely forms of threat to the United States would be through terrorist actions, rather than conventional warfare, and that the spending is still geared towards Cold War-type scenarios and other such conventional confrontations.

[T]he lion’s share of this money is not spent by the Pentagon on protecting American citizens. It goes to supporting U.S. military activities, including interventions, throughout the world. Were this budget and the organization it finances called the

Military Department,then attitudes might be quite different. Americans are willing to pay for defense, but they would probably be much less willing to spend billions of dollars if the money were labeledForeign Military Operations.

DefenseJeopardize Our Safety54, Center For Defense Information, March 9, 2000

And, of course, this will come from American tax payer money. Many studies and polls show that military spending is one of the last things on the minds of American people55.

But it is not just the U.S. military spending. In fact, as Jan Oberg argues56, western militarism often overlaps with civilian functions affecting attitudes to militarism in general. As a result, when revelations come out that some Western militaries may have trained dictators and human rights violators, the justification given may be surprising, which we look at in the next page.

0 articles on “World Military Spending” and 3 related issues:

Arms Trade—a major cause of suffering

The arms trade is a major cause of human rights abuses. Some governments spend more on military expenditure than on social development, communications infrastructure and health combined. While every nation has the right and the need to ensure its security, in these changing times, arms requirements and procurement processes may need to change too.

Read “Arms Trade—a major cause of suffering” to learn more.

Arms Control

Read “Arms Control” to learn more.

Geopolitics

Read “Geopolitics” to learn more.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues