Dominance and Change in the Arctic

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/740/dominance-in-the-arctic.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

The Arctic region has long been considered international territory. Five countries—Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Norway, Russia, and the United States—share a border with the frozen Arctic Ocean. Some of these nations have claimed parts of the region to be their territory. Underlying the interests in the area are potentially vast oil, gas and other resources, as well as the opening up of lucrative passages for trade and economic activity. As a result, these nations have been vying for dominance in the Arctic.

On this page:

Russia claims the Arctic as Russian Territory

In early August 2007, traveling in a mini-submarine, members of Russia’s parliament planted their country's flag four kilometers (2.5 miles) below the North Pole at the climax of a mission to back up Russian claims to the region’s mineral riches.

Apparently the first expedition of its kind to reach the ocean floor under the North Pole, the aim was to establish if a section of seabed passing through the pole, known as the Lomonosov Ridge, is in fact an extension of Russia's landmass.

Russia of course claims it is. Yet, the Washington Post notes the US State Department’s response that the best available scientific evidence suggests the ridges in question are oceanic by nature

. In addition, the Russian media reported that the US had started its own similar expedition earlier and that this may have been a race between the two nations.and thus not part of any country’s continental shelf.

Why interest in the Arctic region suddenly?

The headlines caused by the Russian claim may appear to have been a sudden interest, but the interested parties have, for years, been interested in the potential the Arctic offers.

The US Geological Survey, a U.S. government agency, believes that the region may house approximately 25% of the world’s oil reserves.

Gas, even diamonds, are supposedly to be found there too.

Also lucrative is the opening up of access and trade routes as climate change breaks up more ice. The famed North West Passage across the top of Canada, and the North East Passage (also known as Northern Sea Route) across the top of Russia could become permanent passages, for example.

It is also thought that fishing and tourism could increase in the region. Fishing may alter the already-fragile ecosystem, while tourism is not guaranteed because of uncertainty on the weather patterns that will result from climate change (e.g. more rain would likely reduce tourism).

Russia has attempted similar claims in the past

Russia’s claims, at time of writing, of course are disputed given the potential interests in the resources and potential trade routes emerging in the region.

As early as the 1920s, Russia (then the Soviet Union) made claims to the Arctic. Russia is, however, a party to the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea, limiting it, and the other Arctic four to 200 miles of territorial waters. Under the treaty, these nations are allowed to file claim to the UN commission for more territory. But they have to prove that their continental shelves are geographically linked to the Arctic seabed.

This is what Russia is now claiming (and has done before in 2001, unsuccessfully), and awaiting verification. The Telegraph summarized how all the other nations were interested in similar claims, too:

[The UN commission] warned that Russia was still along way off presenting a credible claim, saying it would not be in a position to do so until 2010 at the earliest.

…

Even so, the development has galvanized other Arctic nations into action. Denmark is to submit its own claim and Canada has announced it will build eight armed ships capable of cutting through the ice.

Both countries are also expected to study the Lomonosov Ridge, which runs through Greenland to Canada’s Ellesmere Island.

The area is believed to have up to 10 billion barrels of oil.

With the United States and Norway also having filed claims, the prospect for bitter territorial disputes has been raised. Russia, however, remains quietly confident.

Furthermore,

If Russia is successful, however, its already mighty energy reserves would be given a massive boost—although there is still doubt about the technical feasibility of extracting oil and gas from the Arctic.

Despite growing concerns over the way Moscow uses its energy for political gain, Russian scientists have repeatedly pledged that there is no intention to grab any part of the Arctic.

A unilateral annexation of the area by Russia is impossible,said Viktor Posyolov of the Russian Institute of Ocean Geology, which has led the Arctic exploration.We will strictly abide by the UN convention.

Many countries in dispute over the region

However, it is not just Russia that is claiming territory in the region; most other countries have, or had, disputes with others. For example, between

- Canada and the US

- Canada and Denmark

- Russia and the US

The BBC provides a summary of some of the disputes:

The United States does not recognize Canada’s sovereignty over the Passage. It has in the past sent its ships on unannounced voyages in order to maintain its claim that the waters are international.

It argues that waters between two open seas have to be open to all shipping. Canada claims this as a unique case. There is now an agreement that the US will notify Canada of such transits but that Canada cannot stop them.

Another Canadian-US dispute is over the Beaufort Sea, which has implications for oil and gas exploitation.

There is also a potential dispute about the so-called North East Passage along the north Russian coast. Here the US feels that Russia is claiming too much territorial water.

…

In 1990, the United States and the then Soviet Union signed an agreement dividing [the Bering] sea which separates Alaska from Siberia.

However the Russian parliament has refused to ratify it, saying that it had taken 50,000 square kilometers away from Russia. This, it is said, would deny Russia 200,000 tons of fish as well as rights to other resources.

(The Telegraph also goes into Canada’s rivalry with the US and Denmark over different parts of the Arctic region in further detail.)

And the Washington Post also adds to this:

The Russians are not the only ones eyeing the Arctic seabed. Denmark hopes to prove that the Lomonosov Ridge is an extension of the Danish territory of Greenland, not Russia. Canada, meanwhile, plans to spend $7 billion to build and operate up to eight Arctic patrol ships in a bid to help protect its sovereignty.

The U.S. Congress is considering an $8.7 billion budget reauthorization bill for the U.S. Coast Guard that includes $100 million to operate and maintain the nation's three existing polar icebreakers. The bill also authorizes the Coast Guard to construct two new vessels.

A senior Russian lawmaker said Wednesday that Moscow also needs to bolster its military forces in the region.

What prompted the interest in the region in the first place? Another article in the Telegraph from 2004, suggests that Canada first laid claim to the North Pole in the 1950s though sovereignty was never granted. Recently, in 2004, Denmark also launched a bid to claim it. That prompted an unseemly scramble among Canadian and Russian scientists who are busily preparing rival arguments over sovereignty.

Accompanying these disputes, claims and counter-claims is inconsistency in arguments, or even double standards. Robert Bridge, writing in the Moscow News for example, notes that while Canada was understandably incensed at Russia’s recent stunt, they have done similar things in the past:

Look, this isn’t the 15th century,reminded Canadian Foreign Minister Peter MacKay.You can’t go around the world and just plant flags and say,We're claiming this territory.It apparently escaped MacKay’s memory that it was not the 15th century, but September 2005, when the Canadian Defense Minister, together with a brave outfit of Canadian soldiers, stormed an uninhabited rock formation off the eastern coast known as Hans Island and raised the Maple Leaf. This

provocationdrew a fiery response from Denmark, which claims the island as part of Greenland.

Bridge also noted MacKay’s erroneous claim that the Arctic was Canadian territory when MacKay said, It’s clear. It’s our country, it’s our property, it’s our water… The Arctic is Canadian.

As mentioned above, it is international territory, although various nations are submitting claims, none of which to date have been successful.

And as DefenseNews.com and the Washington Times reported, Canada is looking to increase its military presence in the region. It is likely that Russia will be doing so too. Nonetheless many experts find that the territory is still very challenging to conquer even though climate change may unfortunately help create more political as well as environmental challenges.

Climate, Environmental and Indigenous Challenges

The existing indigenous population in the circumpolar arctic region face further pressures on their ways of life.

According to UNEP/GRID-Arendal, Except for Greenland and Northern Canada, indigenous peoples form a minority, though they can form the majority in local communities.

They are therefore particularly vulnerable to increased immigration by non-indigenous people as a result of industrial development, and to increased competition for resources.

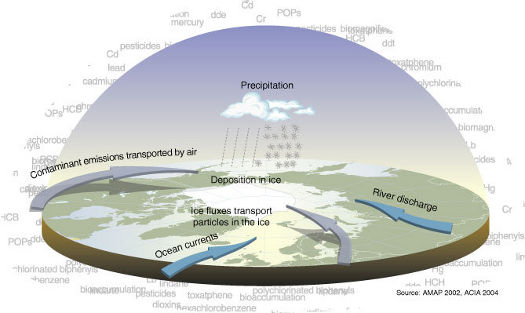

Another problem local populations face is from pollution, often carried by currents and winds from as far away as Russia, Canada and even the United States. Pollutants end up in local wildlife, from seals, fish and whales, which then eventually makes its way into people.

As the video further below also notes, pregnant women in parts of Inuit territory in Canada are advised to avoid certain foods due to increased mercury levels and other toxins. UNEP/GRID-Arendal also adds that this has led to the abandonment of traditional foods, which has also led to more unhealthy food habits acquired from non-indigenous peoples.

See image source for more details.

A third and crucial problem that the fragile arctic region and its indigenous population and wildlife are already facing is climate change.

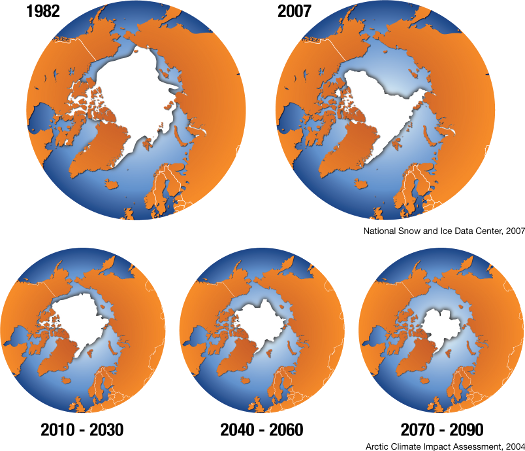

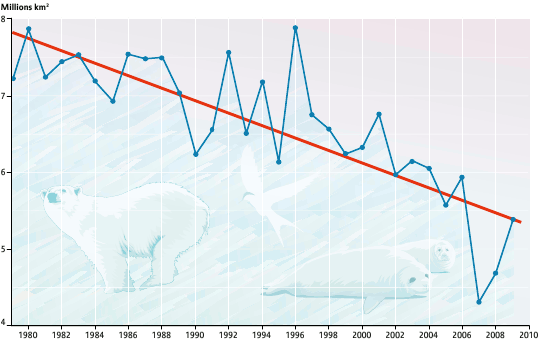

The Arctic sea ice is important in climate change: it reflects most of the sunlight back out to space, thus minimizing excess heat being trapped. With climate change and sea ice melting, there is less sunlight being reflected with more heat being absorbed by the oceans and resulting in even faster warming.

This could cause the Greenland ice sheet melting (which will actually increase sea levels, whereas the melting of Arctic ice will not because it is sea ice), and possibly increase the melting of permafrost in Siberia, which would release huge amounts of methane. Climate patterns such as ocean circulation patterns and jet streams could change quickly leaving little time for ecosystems to adapt.

Satellite observations show the arctic sea ice decreasing, and projections for the rest of the century predict even more shrinkage:

In terms of biodiversity, the prospect of ice-free summers in the Arctic Ocean implies the loss of an entire biome

, the Global Biodiversity Outlook notes (p. 57).

In addition, Whole species assemblages are adapted to life on top of or under ice — from the algae that grow on the underside of multi-year ice, forming up to 25% of the Arctic Ocean’s primary production, to the invertebrates, birds, fish and marine mammals further up the food chain.

The iconic polar bear at the top of that food chain is therefore not the only species at risk even though it may get more media attention.

Note, the ice in the Arctic does thaw and refreeze each year, but it is that pattern which has changed a lot in recent years as shown by this graph:

It is also important to note that loss of sea ice has implications on biodiversity beyond the Arctic, as the Global Biodiversity Outlook report also summarizes:

- Bright white ice reflects sunlight.

- When it is replaced by darker water, the ocean and the air heat much faster, a feedback that accelerates ice melt and heating of surface air inland, with resultant loss of tundra.

- Less sea ice leads to changes in seawater temperature and salinity, leading to changes in primary productivity and species composition of plankton and fish, as well as large-scale changes in ocean circulation, affecting biodiversity well beyond the Arctic.

Older members of the indigenous Inuit people describe how weather patterns have shifted and changed in recent years, while they also face challenges to their way of life in the form of increased commercial interest in the region. This combination of environmental and economic factors put indigenous populations ways at a cross roads as this documentary from explore.org shows:

Will history repeat itself and see indigenous people lose out as others want to exploit the resources of the region, or will they be allowed to have a say in what happens?

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues