Global Food Crisis 2008

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/758/global-food-crisis-2008.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Food prices have been rising for a while. In some countries this has resulted in food riots and in the case of Haiti where food prices increased by 50-100%, the Prime Minister was forced out of office. Elsewhere people have been killed, and many more injured. While media reports have been concentrating on the immediate causes, the deeper issues and causes have not been discussed as much.

Food prices have been rising for a while. In some countries this has resulted in food riots and in the case of Haiti where food prices increased by 50-100%, the Prime Minister was forced out of office. Elsewhere people have been killed, and many more injured. While media reports have been concentrating on the immediate causes, the deeper issues and causes have not been discussed as much.

On this page:

Rising food prices

Reporting for the Institute for Food and Development Policy (also known as Food First), Eric Holt-Giménez and Loren Peabody summarized the rises:

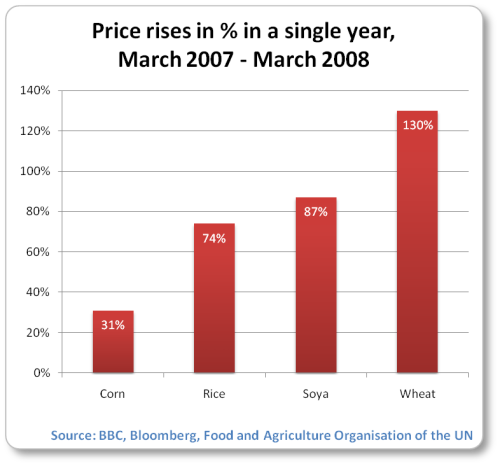

The World Bank reports that global food prices rose 83% over the last three years and the FAO cites a 45% increase in their world food price index during just the past nine months. The Economist’s comparable index stands at its highest point since it was originally formulated in 1845. As of March 2008, average world wheat prices were 130% above their level a year earlier, soy prices were 87% higher, rice had climbed 74%, and maize was up 31%.

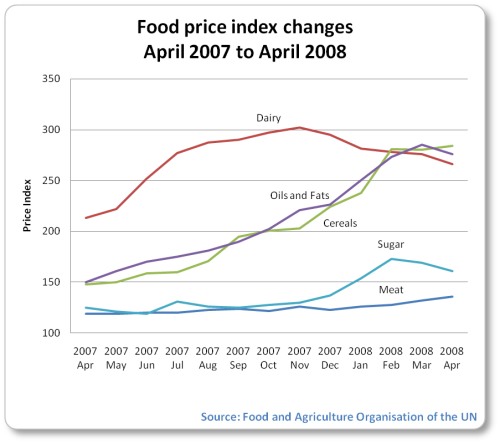

Food price index data from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization show sharp rises in recent months for some food types:

The BBC’s food price statistics as well as Holt-Giménez and Peabody (cited above) both note the sharp rise in basic cereals:

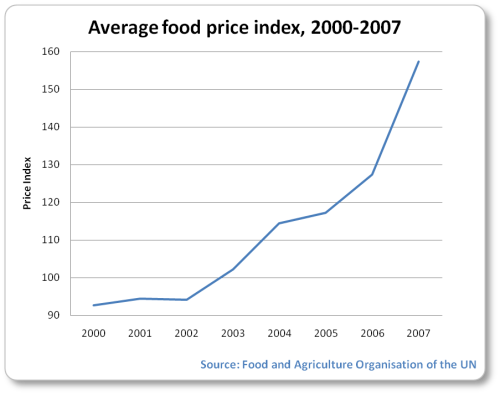

But the crisis was not a sudden one. Prices have been rising for quite some time now, and perhaps earlier warning signs were missed or ignored?

Food prices or overpopulation?

Holt-Giménez and Peabody summarize the issue quite well:

The food crisis appeared to explode overnight, reinforcing fears that there are just too many people in the world. But according to the FAO, with record grain harvests in 2007, there is more than enough food in the world to feed everyone—at least 1.5 times current demand. In fact, over the last 20 years, food production has risen steadily at over 2.0% a year, while the rate of population growth has dropped to 1.14% a year. Population is not outstripping food supply.

We’re seeing more people hungry and at greater numbers than before,says World Hunger Program’s executive director Josette Sheeran,There is food on the shelves but people are priced out of the market.

The overpopulation argument seems like an obvious one, but when considering who consumes what, in what quantities and whether much use of resources are actually productive or not suggests that there may be other issues, though overpopulation concerns could become real at some point.

For example,

- A lot of land goes into producing products that could be considered unnecessary or excessive in their production (e.g. tobacco, sugar, beef, biofuels, urbanization, etc).

- Some 80% of the world’s production is consumed by the wealthiest 20% of the world suggesting an inequality in resource use due to social, economic and political reasons, and perhaps less because of Malthusian concerns about population sizes outstripping resource availability in most cases.

- Furthermore, while many go hungry an equally large number are considered obese.

These aspects are discussed in more depth on this site’s sections on consumption, hunger and population and poverty and hunger.

Causes: short term issues and long term fundamental problems

How has this recent crisis reached this point? As Holt-Giménez and Peabody note, there have been angry demonstrations against high food prices in countries that formerly had food surpluses.

Immediate factors for the food crisis

A number of immediate factors include the following:

- Droughts in major wheat-producing countries in 2005-06

- Low grain reserves (according to Holt-Giménez and Peabody, we have less than 54 days worth, globally)

- High oil prices

- A doubling of per-capita meat consumption in some developing countries

- Diversion of 5% of the world’s cereals to agrofuels.

The above range of issues have been the subject of much mainstream media attention. For example, there has been some debate as to how much of an impact the recent rise in biofuels has actually contributed to the rising prices.

Rich countries wrongly play down impact of biofuels

The US and some European countries have often insisted that the impact of biofuels on the food crisis has been small. It seems that this claim has been self-serving, because of interests in the biofuel industry. Yet, based on the most detailed analysis of the crisis so far,

Biofuels have forced global food prices up by 75%—far more than previously estimated—according to a confidential World Bank report obtained by the Guardian.

The figure emphatically contradicts the US government's claims that plant-derived fuels contribute less than 3% to food-price rises. It will add to pressure on governments in Washington and across Europe, which have turned to plant-derived fuels to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and reduce their dependence on imported oil.

Senior development sources believe the report, completed in April, has not been published to avoid embarrassing President George Bush.

Rich countries have attempted instead to blame demand from rising poorer countries as a bigger cause.

President Bush has linked higher food prices to higher demand from India and China, but the leaked World Bank study disputes that:

Rapid income growth in developing countries has not led to large increases in global grain consumption and was not a major factor responsible for the large price increases.

The report mentions the following ways in which biofuels have distorted food markets:

- Grain has been diverted away from food, to fuel; (Over a third of US corn is now used to produce ethanol; about half of vegetable oils in the EU goes towards the production of biodiesel);

- Farmers have been encouraged to set land aside for biofuel production;

- The rise in biofuels has sparked financial speculation in grains, driving prices up higher.

The World Bank has also estimated that an additional 100 million more people have been driven into hunger because of the rising food prices. Another institute, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimates that 30% of the increase in the prices of the major grains is due to biofuels. In other words, biofuels may be responsible for some 30-75 million additional people being driven into hunger.

With such large numbers of destruction, it is understandable why politically the US and EU may wish to publicly minimize the impact of biofuels.

Deeper, long term causes of the food crisis

However, as Holt-Giménez and Peabody importantly add, all these causes are only the proximate causes of food price inflation. These factors do not explain why—in an increasingly productive and affluent global food system—next year up to one billion people will likely go hungry. To solve the problem of hunger, we need to address the root cause of the food crisis: the corporate monopolization of the world’s food systems.

What the authors are alluding to is the following:

The dominance of the richer nations and companies in the international arena has had a tremendous impact on agriculture, which, for many poor countries forms one of the main sources of income. A combination of unfair trade agreements, concentrated ownership of major food production, dominance (through control and influence in institutions such as the World Bank, IMF and the World Trade Organisation) has meant that poor countries have seen their ability to determine their own food security policies severely undermined.

Policies such as structural adjustment demanded by these institutions meant most developing countries had to not only cut back on health and education, but food stamps and other support for the very poor. Trade barriers and other support mechanisms for local industry were also often required to be removed, allowing foreign companies to more easily compete, often being at an advantage as they would typically be larger multinationals with more resources and experiences.

By comparison, richer countries have hardly reduced their barriers in return. In addition, most poor countries were strongly encouraged to concentrate more on exporting cash crops to earn foreign exchange in order to pay of debts. This resulting reduction in biodiversity of crops and related ecosystems meant worsening environments and clearing more land or increasing fertilizer use to try and make up for this.

Increasing poverty and inequality thus fueled corruption making the problem even worse. Food dumping (while calling it aid) by wealthy nations onto poor countries, falling commodity prices (when many poor countries had to compete against each other to sell primarily to the rich), vast agricultural subsidies in North America and Europe (outdoing the foreign aid they sent, many time over) have all combined to have various effects such as forcing farmers out of business and into city slums. Meanwhile, crop biodiversity dwindled during the promise of the Green Revolution, which also increased chemical input, environmental degradation and felling of forests to bring more land into production.

Food security has reduced as a result and many countries are less able to do things if they want to. Holt-Giménez and Peabody are worth quoting again, this time on the impacts of concentrated ownership:

The expansion of industrial agri-foods crippled food production in the Global South and emptied the countryside of valuable human resources. But as long as cheap, subsidized grain from the industrial north kept flowing, the agri-foods complex grew, consolidating control of the world’s food systems in the hands of fewer and fewer grain, seed, chemical and petroleum companies. Today three companies, Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill, and Bunge control the world’s grain trade. Chemical giant Monsanto controls three-fifths of seed production. Unsurprisingly, in the last quarter of 2007, even as the world food crisis was breaking, Archer Daniels Midland’s profits jumped 20%, Monsanto 45%, and Cargill 60%. Recent speculation with food commodities has created another dangerous

boom.After buying up grains and grain futures, traders are hoarding, withholding stocks and further inflating prices.

Genetically modified foods also increasingly came to be seen as a technical savior. If it worked, food could be grown with higher yields and in places where natural conditions are usually unfavorable. With increasing threats of climate change, it would seem this technology is potentially more important.

Yet, environmentalists from rich countries have raised concerns about the effect on nature if some GM varieties cross-breed with natural varieties, the effect on other aspects of biodversity etc. Technically, some have found that promised high yields are not always the case.

From developing countries the concern has been the ownership of this technology, typically private companies from rich countries. They have attempted to patent resources that developing countries have long used freely and tried to use techniques such as preventing farmers from keeping seeds for future years (which they naturally do) through terminator technology

(which would appear to go against the claim of addressing world hunger).

These concerns go to the heart of food security and accountability to their own citizenry. In addition, what such technologies will not address, however, are the political, economic, social and environmental root causes and choices that govern what is grown, why, how it is priced, and why even when there is enough food, so many cannot afford it.

As professor Richard Robbins notes, food is a commodity:

To understand why people go hungry you must stop thinking about food as something farmers grow for others to eat, and begin thinking about it as something companies produce for other people to buy.

- Food is a commodity.…

- Much of the best agricultural land in the world is used to grow commodities such as cotton, sisal, tea, tobacco, sugar cane, and cocoa, items which are non-food products or are marginally nutritious, but for which there is a large market.

- Millions of acres of potentially productive farmland is used to pasture cattle, an extremely inefficient use of land, water and energy, but one for which there is a market in wealthy countries.

- More than half the grain grown in the United States (requiring half the water used in the U.S.) is fed to livestock, grain that would feed far more people than would the livestock to which it is fed.…

The problem, of course, is that people who don’t have enough money to buy food (and more than one billion people earn less than $1.00 a day), simply don’t count in the food equation.

- In other words, if you don’t have the money to buy food, no one is going to grow it for you.

- Put yet another way, you would not expect The Gap to manufacture clothes, Adidas to manufacture sneakers, or IBM to provide computers for those people earning $1.00 a day or less; likewise, you would not expect ADM (

Supermarket to the World) to produce food for them.… What this means is that ending hunger requires doing away with poverty, or, at the very least, ensuring that people have enough money or the means to acquire it, to buy, and hence create a market demand for food.

More information

The above is a gross oversimplification and these deeper issues and causes have been discussed on this web site for a long time. Rather than attempting to explain those all again here, as well as the above links, refer to this site’s Food and Agriculture Issues section for a series of articles covering these aspects.

Eric Holt-Giménez and Loren Peabody, mentioned above, also provide a useful summary at From Food Rebellions to Food Sovereignty: Urgent call to fix a broken food system, Institute for Food and Development Policy, May 16, 2008

For their July 20 broadcast, Radio Adelaide interviewed me about the food crisis and world hunger. The previous link includes a 20 minute recording of that interview (though it is listed under the August 10, 2008 broadcast).

Image credits: Cornfield in the Evening

, courtesy of Michel Mayerle

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues