Slower Population Growth: The Goods and the Bads

NEW YORK, May 31 (IPS) - Results from the 2020 population censuses in the United States and China recently made headlines. But rather than recognizing the social, economic and environmental benefits of slower rates of population growth for the U.S., China and the planet, much of the media stressed the downsides of slower growth and wrote about population collapse, baby bust and demographic decline.

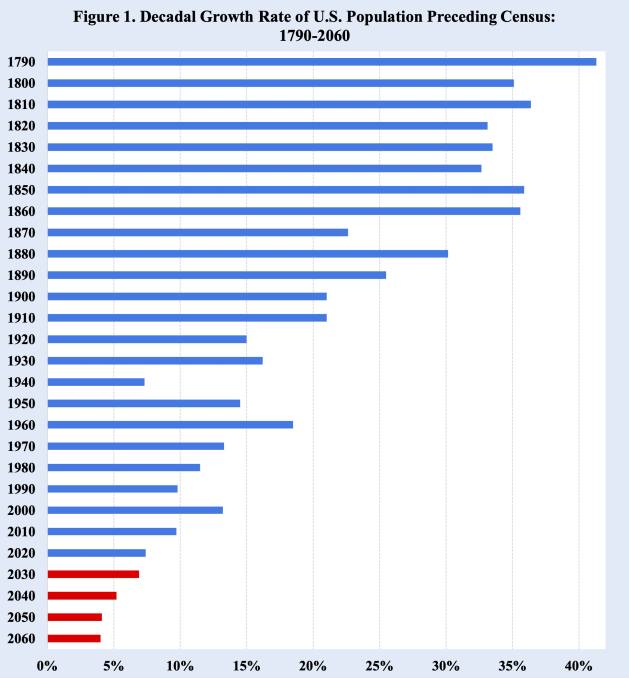

The U.S. population increase of 7.4 percent from 2010 to 2020 was the second lowest rate of growth since the country’s first census in 1790, and half typical growth rates since 1790. Only during the Great Depression of the 1930s did U.S. population grow more slowly, by 7.3 percent. However, even slower rates of U.S population growth are expected in the coming decades (Figure 1).

China's population grew 5.3 percent in the decade ending in 2020, the lowest decadal growth rate since the catastrophic famine of the late 1950s. India projects for 2011-2021 its lowest decadal rate of population growth, 12.5 percent, since its independence.

Lopsided lamentations have focused on the downsides of slower population growth. For example, some commentators who favor more rapid U.S. population growth contend that Americans desire to have more children than they are presently having.

However, while some Americans want more children than they are having, some want fewer. In 2011 (the latest available year), of the 6.1 million pregnancies in the United States, 1.6 million (27 percent) were mistimed and 1.1 million (18 percent) were unwanted at any time. Of all 2011 U.S. pregnancies, 45 percent were not intended.

Some public handwringers maintain that a large population size aids the United States’ competition for economic and geopolitical dominance with China. But the mercantilist view that there is strength in numbers alone is obsolete by centuries. A large or rapidly growing population is hardly necessary or sufficient for prosperity.

Finland, ranked the happiest country in the world, has an average number of children per woman per lifetime of 1.4, compared to the U.S. rate of 1.6 children per woman, South Korea’s 0.8, Singapore’s 1.1, Italy’s 1.3, Japan’s 1.4, Norway's 1.5 and Denmark's 1.7. China currently has an average 1.3 children per woman per lifetime, markedly fewer than the United States (Figure 2).

Some advocates of more rapid population growth argue that it would permit more people who want to move to the U.S. to do so. About 158 million adults in other countries would like to settle permanently in the U.S., according to the Gallup poll in 2018. Would the U.S. willingly accept many or most of these would-be migrants?

More rapid population growth, especially through increased immigration of working-age adults, would temporarily ease the pressures on pay-as-you-go public programs for the elderly, particularly Social Security and Medicare, by broadening the country's tax base.

But there's a catch: in the future those additional workers would retire, requiring additional workers to broaden the tax base again for the retiring workers. This demographic expansion would need to continue indefinitely.

Public discussion has largely ignored the notable social, economic and environmental upsides of slower American population growth. Slower population growth increases economic opportunities for women and minority groups, and exerts upward pressures on wages, especially for unskilled labor.

For a given rate of capital investment, slower population growth also raises capital per person, raising productivity. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grows more slowly, but GDP per person grows faster.

All else equal, slower population growth lessens America’s contributions to climate change, biodiversity loss, deforestation, and pollution from commercial, industrial, agricultural, and domestic activities such as heating and cooling buildings and fueling transport. Slower population growth makes it easier for governments, schools, and civic and religious organizations to adapt to increasing demands of more people.

Worries about impending demographic doom for the U.S. seem decidedly misplaced. The United Nations projects that the populations of 55 countries or areas will decrease by 1 percent or more between 2020 and 2050. China's population is projected to fall by almost 3 percent, Italy by 10 percent and Japan by 16 percent (Figure 3). By contrast, the population of the United States, currently at 333 million, is projected to grow by nearly 14 percent, largely through immigration, to 379 million by 2050.

The world's population growth rate peaked in the 1960s and is falling in most regions except sub-Saharan Africa. Whereas the U.S. population increased nearly four-fold during the 20th century, it is expected to increase by roughly 50 percent in the 21st century.

The United States and many other countries, including China, face real population challenges, but not principally slower population growth or even gradual population decline. The problems include rapid population aging, managing cities and economies in recognition of climate change, regulating and responding to migration, and enabling people to have the children they want through reproductive health care and child-care support.

As COVID-19 has clearly demonstrated worldwide, real population challenges include protecting people against present and future pandemics, maintaining competitive technological change with better investments in education and worker training, and raising the value placed on today's children, who are tomorrow's future problem solvers. In 2021, 22 percent of all children under age 5 years are stunted from chronic undernutrition, despite record cereal production globally.

The global slowdown in population growth rates is not a transitory demographic phenomenon. It signals important durable successes. Couples are having smaller numbers of children in an increasingly urbanized world while men and women pursue education, employment and careers and live longer than ever before.

It is time to recognize that slower population growth benefits America, China, and the Earth.

Joel E. Cohen is Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of Populations at The Rockefeller University and Columbia University in New York and author of “How Many People Can the Earth Support?”.

Joseph Chamie is a former Director of the United Nations Population Division, New York, former research director of the Center for Migration Studies and editor of International Migration Review, now an independent demographer and author of “Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters”.

© Inter Press Service (2021) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Where next?

Browse related news topics:

Read the latest news stories:

- Make America Great Again? Not by This Administration Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Hunger and Heightened Insecurity Pushes Sudan to the Brink of Collapse Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Regime Obstructs Aid, Orders Air Strikes in Quake-hit Myanmar Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Collapse of Gaza Ceasefire and its Devastating Impact on Women and Girls Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Bangladesh Chief Advisors China Tour Cements Dhaka-Beijing Relations Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Greenland: A Brief Chronicle of a US Historical Interest Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- UN Staff Put on Alert -- as US Visa Holders Face Threats and Deportation Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Lebanon: UN expresses deep concern over latest Israeli airstrikes, in call for restraint Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- DR Congo: Surging violence as armed groups target civilians in the east, Human Rights Council hears Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Sudan on brink of famine as fighting ravages Darfur, UN warns Tuesday, April 01, 2025

Learn more about the related issues: