Advancing the Rights of Women Manual Scavengers in India

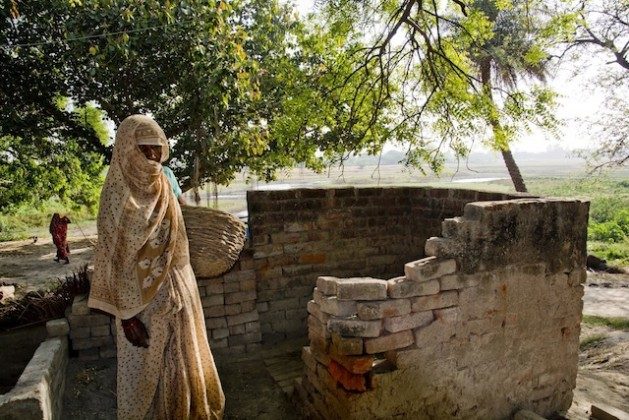

Aug 27 (IPS) - Manual scavenging is a caste-based profession that leads to discrimination and atrocities against those engaged in it. Generations of families from marginalised communities in India have been forced to continue in this profession because of social ostracism and a lack of alternatives.

Despite legislative and judicial interventions since 1993 and the enactment of a new law in 2013, manual scavenging continues in practice. People, especially women, engaged in this profession face systemic exclusion and find it difficult to access healthcare, education, welfare, and social security schemes. They work for negligible wages and accessing alternative livelihoods remains challenging for them, despite government schemes for this very purpose.

The Association of Rural Urban and Needy (ARUN), Centre for Equity Studies (CES), and WaterAid India jointly conducted a survey in four states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh) to highlight these issues. The baseline survey had 1,686 respondents and the end of action survey covered 123 women manual scavengers (WMS) in six locations in two states—Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh.

The findings of the end of action survey reaffirm the caste and gender-based nature of manual scavenging. It also draws attention to the level of awareness about the legal provisions for people engaged in this profession.

The link between caste, gender, and manual scavenging

All the survey respondents belonged to Dalit communities, such as Valmiki, Dom, Hari, and others.

According to the survey, 27.6 percent of the WMS were still engaged in cleaning dry latrines, coming in direct contact with human faeces. These women are informal workers, do not have fixed wages, and are not paid in a timely manner. This was evident as 20.3 percent of the surveyed WMS were unemployed and had no income. The average monthly salary of 64 percent of WMS ranged from INR 240 to INR 4,500.

This is despite the fact that the Minister of Labour and Employment has mandated basic wages for those employed in sweeping and cleaning activities to be INR 350 a day.

Difficulty in finding alternative livelihood options

Several respondents expressed that they had attempted to pursue other livelihood options to move away from manual scavenging, but to no avail. Some have managed to be employed as caretakers or cleaning staff in domestic, public, or institutional settings. Their work, however, still included cleaning toilets.

They were subjected to various forms of discrimination, which impacted their well-being. The localities where they lived often had no household piped water connection and they had limited access to stand posts that supply water.

They are commonly prohibited from eating with other people and have to use separate glasses and utensils in restaurants—in those instances where they are allowed to enter. Women involved in manual scavenging experienced triple oppression—as members of a caste involved in manual scavenging, as women, and as poor people with little or no formal education.

Access to services and schemes

All the respondents had Aadhaar cards, 99.18 percent had voter cards, and 90.24 percent had ration cards. Despite this, several of them reported not being enlisted as women who carry out manual scavenging activities under The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act (PEMSR Act).

Even with the required documents, many of them are yet to be enrolled as people who are employed as manual scavengers. As a result, they have been excluded from several commitments made under the PEMSR Act and Self-employment Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers (SRMS).

For instance, 9.76 percent of the respondents conveyed that their state government had not issued ration cards to eligible households to purchase subsidised food grains from the public distribution system. As several of the WMS did not have the required documents to meet the eligibility criteria, they could not access essential items such as wheat, rice, and sugar.

Awareness of legal provisions

Majority of the respondents (93.93 percent) knew that manual scavenging is prohibited by law and many (77.06 percent) were cognisant of the rules and provisions of the PEMSR Act. Further, 62.88 percent were aware that their employment was illegal.

Only 27.77 percent of the respondents had any knowledge about government schemes specific to their communities, such as rehabilitation and scholarship opportunities. When asked about rehabilitation provisions under the PEMSR Act, respondents revealed that they had faced several challenges. As per the Act, authorities are expected to identify the number of people engaged in manual scavenging and take measures to ensure rehabilitation.

However, among the WMS surveyed, this has not happened. Close to 42.69 percent of them had filed an application or self-declaration to the local authority so they can be identified as a manual scavenger. Only 6.5 percent of the respondents were included in the official list of manual scavengers released by the Government of India. Additionally, 47.1 percent of the respondents had applied for a one-time cash assistance programme under the SRMS. Of this, only 2.4 percent received the sum.

Systemic measures to eliminate manual scavenging

The complete eradication of manual scavenging as a practice can only be achieved once its caste-based nature is acknowledged and systemic measures to rehabilitate and provide adequate compensation are implemented.

1. Improve the legal framework

The definition of manual scavenging in the PEMSR Act must be broadened. It must also recognise the caste-based and generational nature of the profession, and expand the criteria for people to be enrolled under the Act, with clear guidelines for implementers. Alongside this, the enforcement of the provisions of the Act are critical.

2. Better data collection, monitoring, and accountability mechanisms

The government must consistently collect reliable data on people engaged in manual scavenging. This will allow for better rehabilitation measures and enforcement of the PEMSR Act. While the Act mandates every state and union territory to have a State Commission for Safai Karamacharis, only eight of the 28 states have set these up. Thus, it is imperative that state- and district-level commissions be instituted for better monitoring of the PEMSR Act.

3. Provide adequate financing

The SRMS should have adequate budgetary allocation and utilisation by the Department of Social Justice and Empowerment. Departments such as labour, urban and rural development, health, education, and others should be given responsibilities to ensure the upliftment of communities engaged in this work.

4. Increase rehabilitation compensation

Currently, grants for the rehabilitation of WMS under the SRMS are capped at INR 40,000 per individual. However, this amount is insufficient to set up viable enterprises. The National Human Rights Commission has also recommended that this amount be revised to INR 1,00,000. A faster and more efficient process to clear applications and disburse one-time compensation and loans must also be instituted.

5. Normalise use of protective gear and technology

The central and state governments should promote and mandate the provision and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for all sanitation work. They must also prioritise sustainable technology alternatives to eradicate all forms of manual scavenging. Increasing budget allocation for sewage treatment infrastructure or faecal sludge treatments will allow for mechanisation of toilet tank emptying, cleaning, and transportation.

6. Coordinate civil society action

Civil society organisations must make a coordinated effort to improve the health, safety, and dignity of WMS. Organisations working in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector need to come together and work in conjunction with trade unions and the government to ensure that the livelihoods and human rights of people engaged in manual scavenging are protected.

Sharanya Menon is an editorial analyst at India Development Review. In addition to writing, editing, and sourcing content, she also supports the team with website management. Prior to this, Sharanya interned at The Institute of Chinese Studies and The YP Foundation. She recently graduated with an integrated masters in development studies from IIT Madras.

This story was originally published by India Development Review (IDR)

© Inter Press Service (2021) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Where next?

Browse related news topics:

Read the latest news stories:

- Gaza: UN official warns of 'assault on dignity' as blockade cripples humanitarian response Saturday, April 26, 2025

- Venezuela's Oil trapped in Hurricane Trump's Onslaught Friday, April 25, 2025

- Purple Saturdays Movement: Afghan Women Fight for Rights, Justice, and Freedom Friday, April 25, 2025

- African Giving Practices: Understanding a Tradition of Generosity and Community Support Friday, April 25, 2025

- Reclaiming Equity: Why G20 Must Center Women, Children & Adolescents in the UHC Agenda Friday, April 25, 2025

- US Plans at Restructuring May Include World Bank, IMF & UN Agencies Friday, April 25, 2025

- Kashmir Reels After Pahalgam Attack, Fear Long Term Impacts on Livelihoods Friday, April 25, 2025

- Sudan situation ‘absolutely devastating’ as UN ramps up food aid Friday, April 25, 2025

- UN Security Council condemns Jammu and Kashmir terror attack Friday, April 25, 2025

- Destitution and disease stalk Myanmar’s quake survivors Friday, April 25, 2025