The Dying Children Divide

PORTLAND, USA, Sep 05 (IPS) - The chances of a child dying before reaching age five years have dropped substantially worldwide during the recent past. However, a significant divide remains among countries as well as within regions in the chances of children dying.

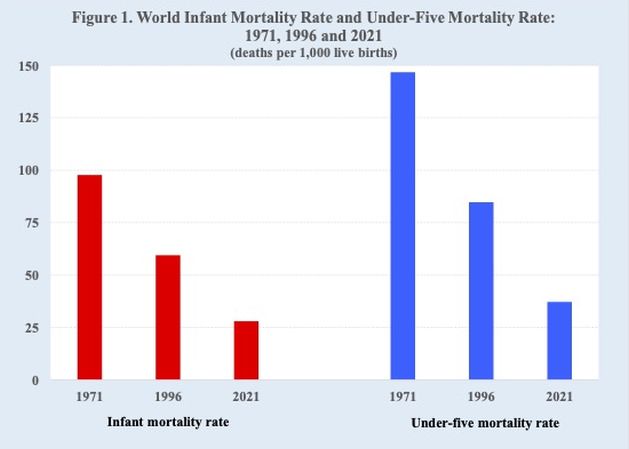

Over the past fifty years, the death rates of infants and children under age five have declined markedly. Since 1971 the world’s infant mortality rate declined from nearly 100 deaths per 1,000 live births to 28. Similarly, the world’s under-five mortality rate declined from nearly 150 deaths per 1,000 live births to 37 (Figure 1).

Despite those impressive declines, sizable differences in the levels of children dying persist especially between more developed and less developed regions. In 2021, for example, the infant mortality rate and under-five mortality rate of the less developed regions were about eight times the levels of the more developed regions.

High rates of children dying are even more striking for many developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. While sub-Saharan Africa represented 14 percent of the world’s population in 2021, it accounted for more than 56 percent of the deaths of children under age five. In contrast, more developed regions represented 16 percent of the world’s population but accounted for 1 percent of deaths of children under age five.

In addition, the infant mortality rates of the fifteen highest countries are all located in sub-Saharan Africa. Their rates are no less than thirteen times higher than those of the more developed regions. Moreover, four of those countries, i.e., Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Central African Republic, and Somalia, have rates that are eighteen times higher than those of the more developed regions (Figure 2).

A similar pattern is clear for death rates of children under-five. The fifteen highest countries are again all in sub-Saharan Africa. They have under-five mortality rates that are at least fifteen times higher than those of the more developed regions. In addition, the rates of Somalia, Nigeria, Chad, and the Central African Republic are about twenty times higher than the levels of the more developed regions.

Important factors contributing to high levels of children dying include neonatal causes, including preterm and low birth weight, asphyxia, infection, pneumonia, malaria, diarrhea, malnutrition, HIV/AIDS, measles, and tuberculosis.

The death of mothers is also a major factor associated with high levels of children dying. High rates of maternal mortality are often the result of excessive blood loss, infection, high blood pressure, unsafe abortion, obstructed labor, anemia, malaria, and heart disease. In addition to high rates of maternal mortality, countries with high death rates of children also have high rates of women dying during their childbearing years.

For the fifteen countries with the highest rates of child mortality, for example, female mortality between age 15 and 50 is at least four times higher than the level of the more developed regions. Moreover, in the Central African Republic, Chad, Lesotho, and Nigeria, female mortality between age 15 and 50 is more than seven times the level of more developed regions (Figure 3).

One of key targets of the Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG 3) is by 2030 to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under five. More specifically, the goals are to reduce neonatal mortality to at least 12 deaths per 1,000 live births and under-five mortality to at least 25 deaths per 1,000 live births.

For most of the sub-Saharan countries achieving those desired goals by 2030 appears unlikely. For example, the under-five mortality rate of sub-Saharan Africa in 2021 is 72 deaths per 1,000 live births, or nearly triple the desired goal by 2030. Also, the projected 2030 under-five mortality rate for sub-Saharan Africa is 62, again more than double the desired goal of 25 deaths per 1,000 births.

The situation for the fifteen countries with the highest levels of children dying are even more striking. The under-five mortality rates of those countries are expected to remain far greater than the desired goal by 2030. For example, the 2021 under-five mortality rates for Nigeria and Somalia of about 111 deaths per 1,000 births are projected to decline to approximately 100 by 2030, or four times the goal of SDG 3.

On a variety of developmental dimensions, the countries with high rates of children dying are doing comparatively poorly. Those countries have high levels of poverty, illiteracy, and malnourishment.

Furthermore, on various global indexes, such as the Fragile State Index, the Human Development Index, the Economic Freedom Index, and the Human Freedom Index, those sub-Saharan African countries are doing comparatively poorly, typically falling in the bottom tier. For example, on the Fragile State Index, the rankings of the fifteen high child mortality countries reflect low levels of economic and social development with high levels of political instability.

Moreover, high child mortality countries are facing increasing risks of climate change. Those countries are among the least able to adapt to its consequences, such as high temperatures, droughts, flooding, and extreme weather events. Also, the same countries generally lack the financial and institutional capacities to carry out adaptation programs.

It is certainly the case that child mortality levels worldwide have declined substantially over the past half century. However, despite those impressive declines, a significant divide in the level of children dying remains between the more developed regions and most sub-Saharan African countries and other countries with high child mortality rates.

The major measures needed to address the high levels of children dying are widely recognized, with most of those deaths being due to preventable or treatable causes. According to the World Health Organization, six solutions to the most preventable causes of under-five deaths are: skilled attendants for antenatal, birth, and postnatal care; immediate and exclusive breastfeeding; access to nutrition and micronutrients; improved access to water, sanitation, and hygiene; family knowledge of danger signs in a child’s health; and immunizations.

It is also widely recognized that the financial resources, political will, social stability, and health programs that are necessary to reduce the numbers of children dying are typically lacking or seriously inadequate.

Addressing the significant divide in the rates of children dying represents a major challenge for many developing countries as well as the international community of nations that can offer aid and assistance to those countries. While the challenge is formidable, it is essential to reduce the unacceptably high levels of children dying.

Joseph Chamie is a consulting demographer, a former director of the United Nations, and his latest book is: "Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters."

© Inter Press Service (2022) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Where next?

Browse related news topics:

Read the latest news stories:

- Make America Great Again? Not by This Administration Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Hunger and Heightened Insecurity Pushes Sudan to the Brink of Collapse Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Regime Obstructs Aid, Orders Air Strikes in Quake-hit Myanmar Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Collapse of Gaza Ceasefire and its Devastating Impact on Women and Girls Wednesday, April 02, 2025

- Bangladesh Chief Advisors China Tour Cements Dhaka-Beijing Relations Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Greenland: A Brief Chronicle of a US Historical Interest Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- UN Staff Put on Alert -- as US Visa Holders Face Threats and Deportation Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Lebanon: UN expresses deep concern over latest Israeli airstrikes, in call for restraint Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- DR Congo: Surging violence as armed groups target civilians in the east, Human Rights Council hears Tuesday, April 01, 2025

- Sudan on brink of famine as fighting ravages Darfur, UN warns Tuesday, April 01, 2025