Q&A: The Undying Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera

WINDHOEK, Aug 29 (IPS) - Legendary and controversial Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera, who once famously told people to let him write and drink his beer, has been dead for 25 years. However, interest in the life and work of the author, who has become a cult icon to aspiring young writers in Zimbabwe and abroad, will not die.

His work continues to inspire authors and readers alike.

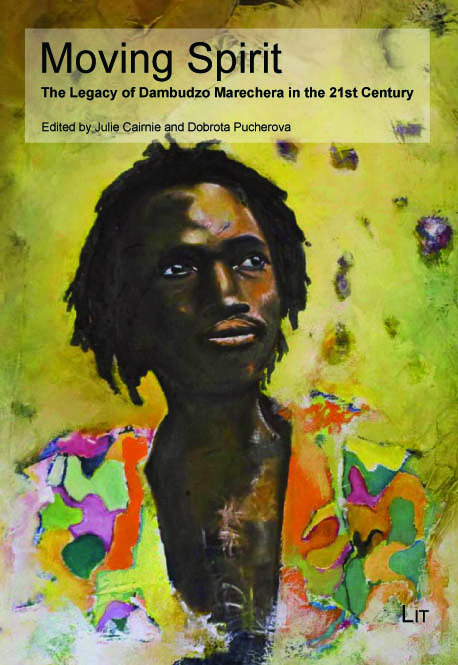

Dr. Dobrota Pucherova’s new edited book on Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera provides new and interesting insights into Marechera’s personal and professional relationships. Courtesy: Dr. Dobrota Pucherova

Dr. Dobrota Pucherova’s new edited book on Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera provides new and interesting insights into Marechera’s personal and professional relationships. Courtesy: Dr. Dobrota Pucherova

Emmanuel Sigauke, a Zimbabwean poet and English teacher at Cosumnes River College in the United States, is a student of Marechera’s work. He tells IPS that many people are drawn to the famous author because of the way he exercised his art, the risks he took, and his total commitment to writing.

Indeed, critics hail Marechera as a genius. His most famous book, House of Hunger, won the prestigious Guardian First Book Award in 1979, making Marechera the first and only African to win the award.

After being expelled in the early 1970s from the University of Rhodesia, now known as the University of Zimbabwe, Marechera was admitted to the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. But he was expelled from there too for unruly behaviour.

He died in Zimbabwe at the age of 35 after spending most of the last five years of his life living in the streets, writing furiously but publishing just one more book, Mindblasts.

Now a book on his life, soon to be released in Zimbabwe, provides new and interesting insights into Marechera’s personal and professional relationships.

Dr. Dobrota Pucherova and Julie Cairnie co-edited the book titled “Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century”. The book, published in Germany in May, is a compilation of essays by various writers that focus on how Marechera continues to inspire others.

“I believe it provides many new insights into Marechera’s relationships with his contemporaries, with other authors, and with his fans and inspirees. For example, Carolyn Hart’s essay explores Marechera’s relationship with African-American postmodern writers, while Katja Kellerer’s piece examines the intertextualities between House of Hunger and Ignatius Mabasa’s Mapenzi,” Pucherova says.

She holds a PhD on southern African writing and studied Marechera’s writing as part of her thesis. She also lectures on his work.

Excerpts of the interview follow.

Q: What drew you to the Marechera phenomenon?

A: Marechera’s writing expresses very well the desire for mental freedom that concerned me when studying southern African authors. He believed that overcoming oppositional identity discourses and freeing the imagination to create space for individual reinvention could achieve true liberation from oppression.

At the same time, Marechera’s vision of the political as sexual and the sexual as political provided new insights into power relationships in colonial and post-colonial conditions. Last, but not least, his flair for language and his infectious humour make his books very pleasurable to read.

Q: What inspired this book?

A: When I was writing my thesis chapter on Marechera, alongside I wrote a play based mainly on (his novel) Black Sunlight. To me, this novel is immensely comical and at the same time sophisticated. I felt that it has been misunderstood due to Marechera’s unwillingness to edit his work, as (leading academic publisher on Africa) James Currey has documented.

In adapting the novel for the stage, I wanted to bring forth its audacity and deeply sophisticated comedy. And so, when I decided to produce the play at Oxford, I felt: ‘Why not organise an entire festival on Marechera?’

The festival, which took place from May 15 to 17, 2009, was an international multi-media event that included film, theatre, fiction, poetry, painting, photography, memoirs and scholarly essays – all inspired by Marechera’s work and life.

The book is the proceedings of the festival, with a few additional pieces. Julie Cairnie, who has co-edited the book with me, was a participant at the Oxford Celebration.

Dr. Dobrota Pucherova and Julie Cairnie co-edited the book titled “Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century”. Courtesy: Dr. Dobrota Pucherova.

Dr. Dobrota Pucherova and Julie Cairnie co-edited the book titled “Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century”. Courtesy: Dr. Dobrota Pucherova.

Q: Essays by Marechera’s contemporaries like Musaemura Zimunya, Stanley Nyamfukudza and Charles Mungoshi are conspicuously absent from your compilation. How do you explain this?

A: The majority of contributions in the book were presented at the Oxford Celebration. The people you mention did not respond to the call for papers, which was widely distributed.

Q: Some people think this is the chink in this book’s armour. What impact do these omissions have on it?

A: No book on Marechera can possibly be complete. There are other famous contemporaries of Marechera who are not included in the book.

Q: This new book comes with rare, archival materials that include audiovisuals such as Marechera’s address at the Berlin Conference in 1979, and the speech on African writing that he gave in Harare in 1986. How important is it?

A: This material shows Marechera in various periods in his life. For me, seeing Marechera interviewed by (veteran journalist) Ray Mawerera in Harare in 1984 was a completely different experience than watching him drunk and deeply depressed in the London squat as he appears in Chris Austin’s film (based on House of Hunger). In the Mawerera interview, Marechera is an entirely different person – calm, communicative and composed.

Q: After this book – which is complete with archival material, footnotes, references as well as German scholar and Marechera’s former partner, Flora Wild’s, contribution – what else remains to be learnt about Marechera?

A: I believe no book on Marechera can be complete and I am sure there will be other books on (him). Helon Habila’s biography of Marechera is due to be published next year, and I look forward to reading it.

Q: What, in your view, sets Marechera distinctly apart from his contemporaries and today’s writers?

A: Marechera reacted to the Marxist and nationalist tradition in African writing with cosmopolitanism and post-racialism at a time in Zimbabwean history when it was most controversial to do so.

He described the violence of the colony and post colony with a liberating laughter and dared to laugh even at the power presumptions of the anti-colonial struggle. Identifying language’s key role in upholding systems of power, he explodes language to create new meanings and paradigms.

Moreover, Marechera dared to go to those places in the human psyche where no other black African writer before him had gone.

Others have done so after Marechera – of these, I would mention Yvonne Vera and Kabelo Sello Duiker, who similarly explore the dark spaces of the mind and whose highly poetic but authentic language sets them apart from other African writers. It is very sad that both of these writers have died young, just like Marechera.

© Inter Press Service (2012) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues