Open or Closed Borders, or Something in Between?

NEW YORK, Oct 25 (IPS) - Recent elections around the world have clearly shown growing public support for candidates and political parties advocating the deportation of migrants and stricter restrictions on immigration, including halting it altogether. At the same time, opposition,challenges and resistance to deportations and immigration restrictions have become more widespread, visible and vocal.

As countries wrestle with immigration policies and decide on how best to deal with immigrants and national borders, it is an instructive and useful exercise to review key dimensions of international migration and consider some of the major demographic consequences of opting for open or closed borders, or something in between.

Worldwide, international migrants account for a relatively small share of the total global population, approximately 250 million or a little more than three percent of the world's population of 7.6 billion. While the total number of immigrants has more than tripled during the past half century, the proportion of immigrants has remained between two to three percent of world population.

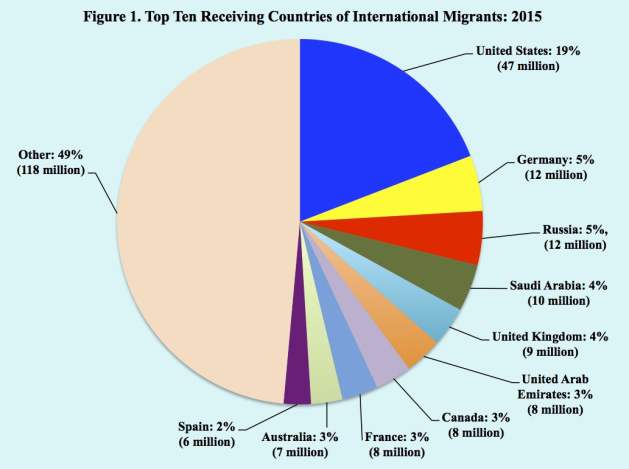

Immigrants are not distributed evenly across the global. Most immigrants are concentrated in a small number of mainly developed countries. More than half of the world's immigrants, for example, are concentrated in ten countries.

The country hosting the largest numbers of migrants is the United States with nearly 47 million immigrants or nearly one-fifth of the world total. In second and third places are Germany and Russia, each hosting about 12 million immigrants, followed by Saudi Arabia with 10 million and the United Kingdom with 9 million (Figure 1).

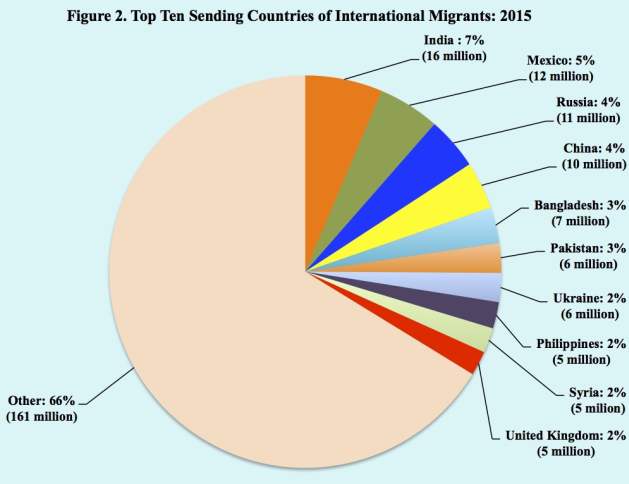

While most immigrants are hosted in mainly developed countries, their national origins are primarily from developing countries (Figure 2). India accounts for the largest number of emigrants, 16 million or 7 percent, followed by Mexico (12 million), Russia (11 million) and China (10 million). The top ten migrant sending countries account for one-third of all emigrants; the addition of another twelve countries represents about half of all international migrants.

At the global level international migration has relatively little demographic consequence on the world's total population. By the close of the century, for example, the world's projected population with and without migration differs by less than 0.02 percent, 11.18 billion versus 11.17 billion, respectively.

At the country level, however, international migration often plays a significant role in demographic change, not only affecting the size of a country's population but also altering its age structure and population composition. In addition, it is important to keep in mind that the demographic consequences of international migration are not only due to the number of the migrants, but also to the subsequent descendants of those migrants.

The demographic impact of international migration on population growth is clearly evident in the case of the European Union. From 1960 to the early 1990s natural increase (births minus deaths) exceeded net migration (immigrants minus emigrants). Since then, largely as a result of low fertility rates, net migration has remained greater than natural increase and in recent years has accounted for nearly all of the growth of the EU population. In 2016, for example, EU's population change due to net migration was 1.5 million, while the contribution of natural increase was a negative 15 thousand.

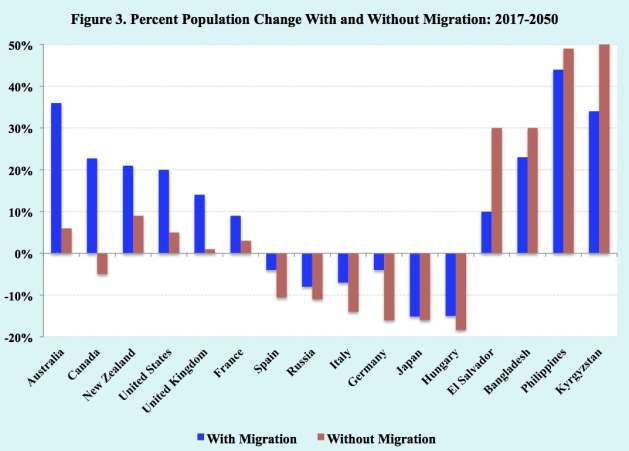

The potential impact of international migration on the future size of populations may be ascertained by considering population change with and without migration across countries with different demographic circumstances. For some countries, especially the traditional immigration countries, such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, as well as France and the United Kingdom, international migration accounts for a substantial amount of future population growth over the next several decades (Figure 3).

In the case of Canada, the absence of international migration implies a decline of about 5 percent in its current population size by midcentury and more than a 25 percent decline by the close of the century. Again as observed in the EU, the sizeable effect of immigration on Canada's future population is largely the result of Canadian fertility rates falling well below the replacement level of approximately two births per woman.

In other developed countries, such as Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Spain and the Russia, international migration reduces the expected declines in their future populations due to their projected negative rates of natural increase. In Germany, for example, the absence of international migration is projected to result in a 16 percent decline in its population by 2050 and more than a 40 percent decline by the end of the century.

For traditional emigration countries, such as Bangladesh, El Salvador, Kyrgyzstan and the Philippines, their projected populations would be decidedly larger in the future without the outflow of their emigrants. In El Salvador, for instance, its population by mid-century is expected to experience a 10 percent increase with migration versus a 30 percent increase without migration.

In addition to its effects on future population size, international migration can also have important consequences on a country's age structure. In particular, immigration typically adds young working-age people, thereby stabilizing or increasing the size of the labor force as well as contributing to slowing population aging in the near term. By and large, however, current immigration levels do not constitute a solution to an aging population insofar as the immigrants themselves also age and eventually retire.

A country's population composition is also affected by international migration. Many of those migrating today are ethnically, religiously and culturally different from the populations of the receiving countries. Such migratory flows are contributing to increased ethnic and cultural diversity among migrant receiving countries.

In many countries, however, including Austria, Czechia, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Japan, Poland and South Korea, ethnic/cultural homogeneity is widely viewed as a positive characteristic. Immigration policies in those countries stress closed borders strictly limiting immigration to a select group of persons who would maintain the country's ethnic homogeneity and dominance. Also, the rise of nationalism among those countries has often evolved into nativism, xenophobia and the rising influence of far-right political parties.

In contrast to those opting essentially for closed borders, the advocates of open borders or large-scale migration emphasize that permitting people to move freely across international borders would reduce global poverty as well as provide substantial economic and demographic benefits to both migrant sending and receiving countries.

Advocates also contend that open borders would eliminate illegal immigration, human smuggling and deaths of migrants desperately attempting to reach their desired destinations. In short, they consider the increased flow of immigrants across borders to be a "win-win" situation for all concerned.

The demand for immigrant workers in receiving countries, however, is far less than the pool of potential migrants in sending countries. Based on international surveys, the number of people indicating a desire to immigrate to another country is estimated at about 1.3 billion, far larger than the current 250 million migrants worldwide. Also, some 40 million potential migrants have taken steps to emigrate, which greatly exceeds the world's average level of approximately 6 million migrants per year.

In addition to tightening their borders, many countries have stepped up efforts to deter illegal migration and deport unauthorized migrants residing within their borders. However, governments are encountering difficulties in deterring illegal migration and deporting unauthorized migrants. Faced with large numbers of unauthorized migrants who have become established within communities, governments often conclude that legalization may be the preferred policy option.

International agencies and non-governmental organizations are also actively working with governments to develop a global compact for safe, regular and orderly migration to be adopted at a United Nations conference on international migration in 2018. However, based on current global affairs, especially widening armed conflicts, proliferating terrorist acts and increased refugee flows, coupled with the ironclad recognition of national sovereignty over international migration matters, the chances of adopting a meaningful global migration compact appear doubtful.

With the notable exception of the European Union where open borders exist among its members, no other nations have adopted an open border immigration policy. On the contrary, many countries are moving to strong or closed borders. While after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 there were only 15 border walls, today there are 70 of them. Also, three-quarters of all current border walls and fences were erected after the year 2000.

In sum, despite increasing globalization, immigration's touted economic benefits, demographic concerns regarding population decline and aging and commendable attempts to adopt a global compact on international migration, it appears that countries are increasingly opting for limiting the flows of people across borders.

© Inter Press Service (2017) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues