Here’s How the World Can Be Better Prepared to Handle Epidemics

ABUJA, Jul 19 (IPS) - The 2019 G20 Summit was held recently in Osaka, Japan. The Summit ended with the "G20 Osaka Leaders' Declaration", which identifies health as a prerequisite for sustainable and inclusive economic growth, and the leaders committed to various efforts to improve epidemic preparedness.

These efforts are commendable, but the G20, comprised of 19 countries and the European Union with economies that represent more than 80 percent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), also must do more to lead by example in epidemic preparedness by ensuring they all have a ReadyScore.

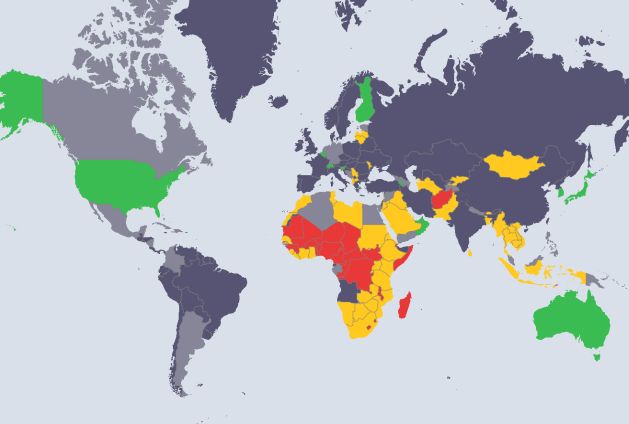

This is managed by preventepidemics.org, the world's first website to provide clear and concise country-level data on epidemic preparedness. It measures a country's ability to find, stop and prevent health threats. Then, they need to demonstrate they are ready to take steps to improve their score, as needed.

This is an important issue because within 36 hours, an infectious disease can travel from a remote village and can be carried to major cities worldwide, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). If anything kills over 10 million people in the next few decades, it would mostly likely be a highly infectious virus rather than a war. The next disaster is not missiles, but microbes, said Bill Gates in his 2015 TED Talk.

As Gates was giving his 2015 TED Talk, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa was coming to an end after causing the deaths of over 11,300 people, reducing the GDPs of Guinea, Liberia & Sierra Leone by $3 billion and devasting the health workforce in the three countries. Overall, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa cost global economy an estimated $53 billion.

Outbreaks are not a thing of the past, however. In 2019, there are measles outbreaks in the US and Europe; Ebola outbreak in DRC and Uganda and several other infectious disease outbreaks in Nigeria, Vietnam and South Africa.

To be assigned a ReadyScore, countries should undergo a Joint External Evaluation (JEE) which is a voluntary, collaborative, multisectoral process to assess country capacities to prevent, detect and rapidly respond to public health risks whether occurring naturally or due to deliberate or accidental events.

Right now, only 100 out of 195 countries (51 percent) have conducted the JEE. Until all 195 countries conduct the JEE, it would be difficult to assess global preparedness for prevention, detection and response to epidemics.

Based on records on preventepidemics.org, the following G20 countries have an unknown ReadyScore; Brazil, China, France, India, Italy, Russia and Turkey. An unknown score implies that a country has not volunteered to have a JEE. On the other hand, the ReadyScore of Argentina, Canada, Germany and Mexico is pending.

This means that they have committed to have a JEE, but data are unavailable. Some G20 countries that do have a ReadyScore include United Kingdom (84 percent), USA (87 percent), South Africa (62 percent), Indonesia (64 percent) and Japan (92 percent).

To be better prepared for epidemics, a country must have a ReadyScore of 80 percent and above, otherwise the international community cannot categorically say that all G20 countries can prevent, detect and rapidly respond to infectious disease outbreaks. So, what needs to happen next?

First, the G20 should work with the World Health Organisation and other partners to conduct JEE to make our world safer. JEE is a voluntary activity and no nation can be compelled to conduct one and very few G20 countries have their ReadyScore. The WHO on its own must strengthen advocacy to the G20 countries that have no ReadyScore. The advocacy should make these countries acknowledge that when it comes to epidemic preparedness, the world is as strong as its weakest.

Second, universal health coverage and global health security must both be addressed together. Billions of people do not have access to healthcare, and this poses serious risks for global health security. As long as there are communities globally in which people are unable to access healthcare because of their inability to pay or due to other inequities, the risks of infectious diseases remain.

A number of G20 countries already fund different health interventions in low- and middle-income countries. It is time for the G20 to push for integrated health programs instead of the current vertical system in recipient countries. Universal health coverage is heavily dependent on political will.

Therefore, the G20 should use its influence to advocate to countries without universal health coverage to gradually move to one. Development aid to such countries earmarked for health should be conditional – to be used to develop a publicly-funded universal health coverage health system which is accessible to all.

Third, G20 countries can invest in networks of reference and specialised laboratories as part of disaster prevention. Detection and control of infectious diseases is delayed if bio samples have to be taken to other countries located thousands of miles away in order to get definitive diagnoses.

For example, during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, to confirm Ebola in Nigeria, blood samples had to be taken to Senegal (more than 3 hours by flight). This obviously delayed the response efforts. Although the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) has since increased its diagnostic capacity, national public health institutes such as NCDC still require financial and technical support to ensure global health security.

G20 countries should lead by example and get a ReadyScore by being open for joint external evaluations and meet all Osaka Leaders' global health commitments. If other countries follow suit, then the world would move closer to being better prepared to handle epidemics.

Dr. Ifeanyi Nsofor is a medical doctor, the CEO of EpiAFRIC, Director of Policy and Advocacy for Nigeria Health Watch

© Inter Press Service (2019) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues