World’s Spreading Humanitarian Crises Leave Millions of Children Without Schools or Education

UNITED NATIONS, Oct 24 (IPS) - As massive protests escalated worldwide last month, millions of children walked out of schools to demonstrate against the lackadaisical response – primarily from world leaders --to the ongoing climate emergency resulting in floods, droughts, typhoons, heat waves and wildfires devastating human lives.

Gordon Brown, a former British Prime Minister and UN Special Envoy for Global Education, rightly pointed out a harsh reality: there are also millions of children who, ironically, have no schools to walk out from.

The figures are staggering: there are 260 million who don't go to schools, mostly because there are none, while the education of an estimated 75 million children have been disrupted by humanitarian crises.

One of the UN's 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG4) is aimed at ensuring that everyone—"no matter who they are, or where they live" – can access quality education by the targeted date of 2030.

But achieving that formidable goal has been undertaken by Education Cannot Wait (ECW) described as the first global, multi-lateral fund dedicated to education in emergencies.

Launched in 2016, and hosted by the UN children's agency UNICEF, ECW has provided educational opportunities, in its first two years of operation, to 1.4 million children caught up in the widespread humanitarian crises.

And ECW has invested in 27 countries, including Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lebanon, Nigeria, State of Palestine, Somalia, Syria, Uganda, Yemen and Zimbabwe, providing schools and quality education in crisis settings.

But still, it has a long way to go because, at the current rate of progress, about 225 million young people will not be in school by 2030.

At a high-level UN summit meeting in September, ECW got a big boost, when world leaders pledged a record $216 million for children's education.

Asked how confident she was that the ECW can help meet SDG4 – particularly when the UN remains skeptical of eradicating poverty and hunger by 2030, ECW Executive Director Yasmine Sherif said: ‘I have hope that we can narrow the gap for the SDG4 target and at Education Cannot Wait, we are all highly motivated to contribute'.

However, she said, this will require increased, bold financial investments and funding in SDG4, especially for the 75 million children and youth left furthest behind in countries of conflicts, disasters and displacement.

ECW has put in place a business model that in a short period of time has proven to work and accelerate SDG4, said Sherif, a human rights lawyer with 30 years of experience in international affairs, including 20 years in management & leadership, and graduated with an LLM from Stockholm University in 1987 and joined the United Nations in 1988.

It is a model that translates the UN reform agenda and the New Way of Working into joint programming with governments, UN agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), enjoys strong strategic buy-in from donor partners who are increasingly investing in ECW as a catalytic and speedy funding mechanism, while also rolling out the Grand Bargain commitments, including the localization agenda, cash-assistance and significantly contributes to strengthened humanitarian-development coherence, she declared.

"In other words, the political will is there, organizational partners are committed to working together, and ECW's investments are crisis-sensitive and rapid, while also focused on quality. Together with our partners, we move with humanitarian speed to achieve development depth. The determining factor will thus be financing."

She pointed out that quality, inclusive education costs money and those costs are significantly higher in situations of armed conflicts, forced displacement and natural disasters, where the education sector is often partially or wholly destroyed, where access is a major challenge and where insecurity, the constant threat of violence and an ever-changing environment requires extraordinary precautions and measures.

"That is why these children and youth are left furthest behind in the first place, and we intend to reach them. But it largely depends on increased, urgent financing. ECW is calling on world leaders, private sector and philanthropic organizations to mobilize $1.8 billion by 2021 to reach children and youth caught in emergencies and protracted crises with education".

Over the longer term, research from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) in 2016 estimated that up to 2030, US$8.5 billion will be needed annually from the international aid community to provide a basic education package for the estimated 75 million children affected by crises, that is, US$113 per child, said Sherif who has served in New York, Geneva and in crisis-affected countries in Africa, Asia, Balkans and the Middle East.

Excerpts from the interview:

IPS: In terms of access to children in conflict situations, what crisis has been the most difficult? Yemen? Afghanistan? Syria? How do you monitor these situations? Or are most children in these war-ravaged countries left out of your mandate -- perhaps due to security and/or lack of access reasons?

SHERIF: Education Cannot Wait was established at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016 with a mandate to reach 75 million children and youth left behind due to emergencies and protracted crises. Our mandate is precisely that: to reach them.

The more exposed they are, the more insecurity that envelopes them, the more deprivation and injustice they suffer, the stronger is our incentive and responsibility to ensure they can claim their right to quality education. Yes, access is very difficult during an active armed conflict. Yet, we must together with partners find solutions to overcome the challenges and obstacles. The ultimate solution is of course a political one: peace.

So far, Education Cannot Wait and our in-country partners - including host-governments, UN agencies, civil society, private sector - and importantly, local organizations, communities, teachers and parents - have reached over 1.5 million girls and boys in the past 24 months and the numbers keep rising.

For a variety of reasons, not least insecurity and access, Yemen is a herculean challenge for delivering on a development sector like education. Still, we have been able to deliver partial education support to an additional 1.3 million children and youth who were consequently able to take end-of-cycle exams and receive food rations. As this type of assistance is different from the assistance provided in other countries, ECW beneficiaries in Yemen are featured separately.

IPS: Besides conflicts, forced displacement and natural disasters hindering SDG4, isn't the lack of education also remotely linked to widespread poverty in developing nations? Is there a co-relation between the two?

SHERIF: Absolutely. In fact, it is not question of a lack of education being remotely linked to poverty, there is in fact a direct correlation. It is all interrelated: education and poverty; education of girls and gender-inequalities; education and the rule by force as opposed to the rule of law.

Indeed, quality and inclusive education - SDG4 - is the very foundation of all the other SDGs. How is it possible to build a socio-economically viable society if the citizens and refugees in that society cannot read or write, cannot think critically, have no teachers, no lawyers, no doctors.

Education is a sound economic investment: for each dollar invested in education, more that $5 is returned in additional gross earnings in low-income countries. Education empowers the most marginalized: a child whose mother can read is 50% more likely to live past the age of five.

Education is key to promoting peace, tolerance and mutual respect: it reduces the likelihood of violence and conflict by 37% when girls and boys have equal access to education.

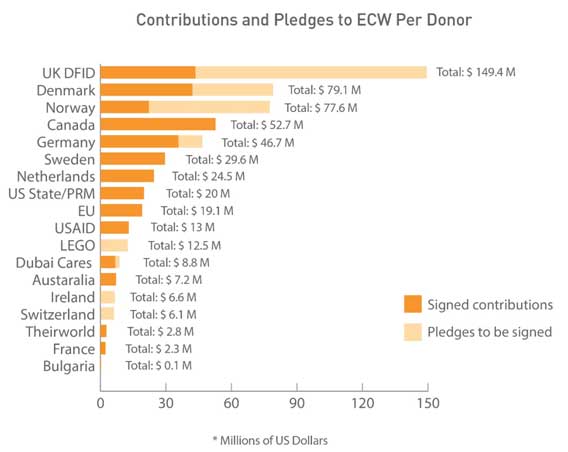

IPS: Are Western nations the only major donors for ECW? Are there any political and economic heavy weights such as China, Saudi Arabia and India who are donors or potential donors?

SHERIF: There are currently 18 strategic financial donor partners to Education Cannot Wait and each year new partners join up with our movement. These include governments, private sector and philanthropic organizations from various regions including North America, Europe, Oceania and the Middle East.

As a vote of confidence in the progress we are achieving, several early partners have already recommitted new funding. As the global, multilateral fund for education in emergencies and protected crisis hosted by the United Nations with its 193 UN Member States, we believe that increasing investments in Education Cannot Wait will continue to encourage more strategic donor partners in the larger UN family - whether they are from the north or the south, east or west.

We are all one humanity, and we have a collective responsibility to ensure that all children and youth in conflicts, natural disasters and displacement can exercise their human right of a quality education. IPS: On fundraising and educational goals, is there any coordination between ECW and the International Finance Facility for Education (IFFED)? if not, how different are they?

SHERIF: We have a shared understanding of the colossal needs to address the challenges of education worldwide and ECW and IFFED are very complementary. So, coordination and cooperation come very easily.

The most optimal coordination always occurs where there is a shared vision and a clear division of labor. ECW and IFFED have two different business models and each targets different sides of the same coin, which allows us to maximize collective impact in each context. The same complementarity pertains to GPE, which also has a different business model and focus.

All approaches are needed and by complementing each other's efforts, we can achieve real results for children. No one can do it alone. In the field of service, it is all about working together, complementarity and collaboration. IPS: Can the funds you raise be described as un-earmarked core resources, or are some of them earmarked by donors as to where you should spend them-- and on which humanitarian crisis? In short, do you have a free hand or are they funds with strings attached?

SHERIF: More than half of the funding ECW has is unearmarked, though we do also have some earmarked funds. We have a shared understanding among our strategic donor partners based on a comprehensive financial analysis, humanitarian and development needs assessments.

There are no political strings that hamper the operations and we work on the basis of combined humanitarian principles (humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence) and development principles (national ownership, capacity development and sustainability).

ECW adheres to organizational standards of accountability, transparency and risk-mitigation, and our donors are proactive and strategic partners in all of this. So, from these important principles and perspectives, while we do not have a free hand to do whatever we want, thankfully, we are free to effectively and speedily serve those left furthest behind. And, that is the greatest freedom of all.

If you want to learn more about Education Cannot Wait and its efforts to get children and youth caught in armed conflicts, forced displacement, natural disasters and protracted crises, please follow ECW on Twitter at: @EduCannotWait and visit their website here: https://www.educationcannotwait.org/"

© Inter Press Service (2019) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues