Widowhood: Stressful and Unprepared

NEW YORK, Feb 03 (IPS) - In addition to the emotional stress and sorrow of widowhood, most people are unprepared to deal with the daunting challenges following the death of a spouse. Rather than treating widowhood as a taboo subject or something to ponder only in old age, couples need to discuss, plan and make decisions early on regarding the eventual and inevitable passing away of one's spouse.

In general, the term widowhood relates only to married couples. However, with the growing incidence of cohabitation, civil unions and partnerships, some countries have broadened the concept of widowhood to include those who have survived the loss of a long-term partner.

Statistics on widowhood typically refer to current marital status. National population censuses, registrations and surveys do not generally gather information on the previous martial status information of those who have remarried after widowhood.

Consequently, the numbers of people who have experienced widowhood are greater than the sums of current widows and widowers.

The estimated number of widowed persons worldwide in 2020 is approximately 350 million, with the large majority, approximately 80 percent, being widowed women. While globally about one out of every 15 people in the marital ages are widowed, country rates vary enormously across a broad range.

Widowhood levels are largely determined by the age and sex structure, mortality rates, including war fatalities, marital ages and rates of marriage, divorce and remarriage.

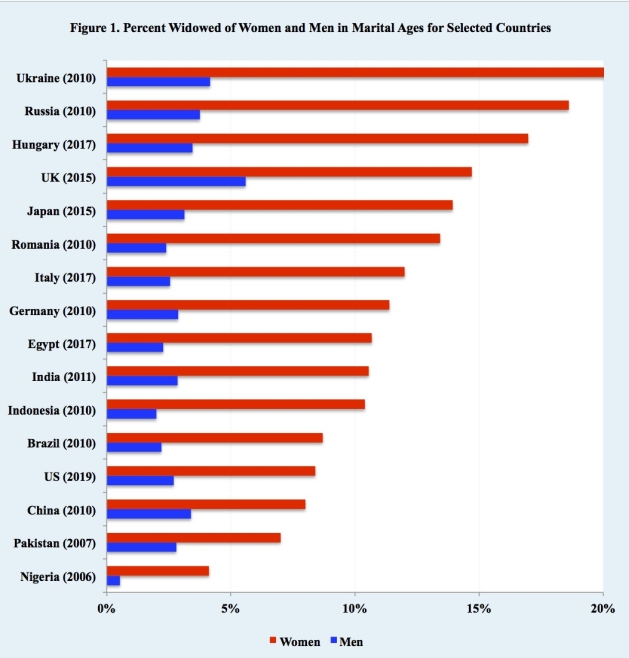

One widowhood pattern, however, that is universal is the rates for women far exceed those for men. For this reason, it is often remarked that widowhood is predominantly a woman's experience.

Irrespective of region, level of development, government, culture, etc., women are substantially more likely to experience widowhood than men. In Russia and Ukraine, for example, the proportions widowed among women and men in marital ages are 20 and 4 percent, respectively.

Even in countries were overall widowhood rates are lower, such as China, Nigeria, Pakistan and the United States, women's widowhood rates are more than double those of men (Figure 1).

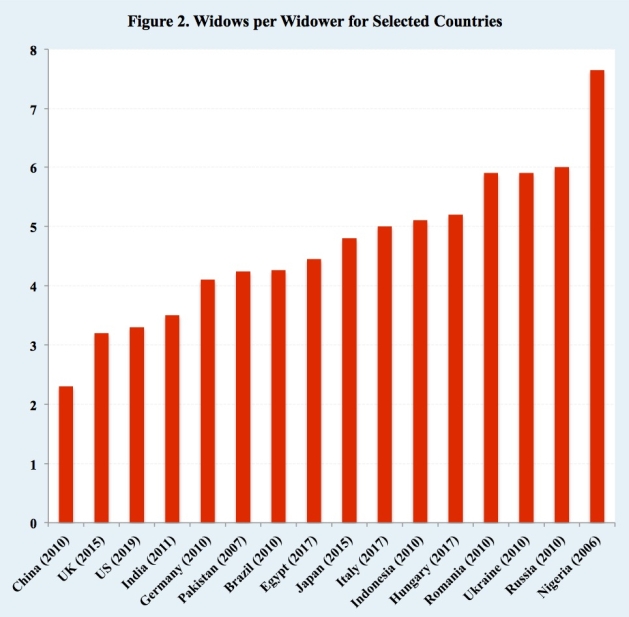

Another useful measure of the prevalence of widowhood is the number of widows per widower. That number spans a wide range from lows of two or three widows per widowers in countries such as China, the United Kingdom and the United States to highs of six to eight in countries, such as Nigeria, Russia and Ukraine (Figure 2).

That measure also illustrates that even though the overall level of widowhood may be comparably low, the number of widows per widower can be high.

In Nigeria, for example, while the percent widowed for women and men is among the lowest at 4 and 1 percent, respectively, the number of nearly 8 widows per widower is among the highest.

A number of important demographic factors contribute to the gender differences in widowhood rates. In addition to women generally being at least several years younger than their spouses, women have lower mortality rates and survive to older ages than men.

Gender differences in mortality can be relatively large with young men dying at a faster pace than normal resulting in high widow rates, as has happened in Russia and Ukraine. As a result of young men's comparatively high death rates, the Russian and Ukrainian sex ratios at age 50 have declined to 87 men per 100 women, substantially lower than the typical sex ratio of 100 or more observed in most developed countries, such as Germany (102), Japan (102), Sweden (103) and the United States (101).

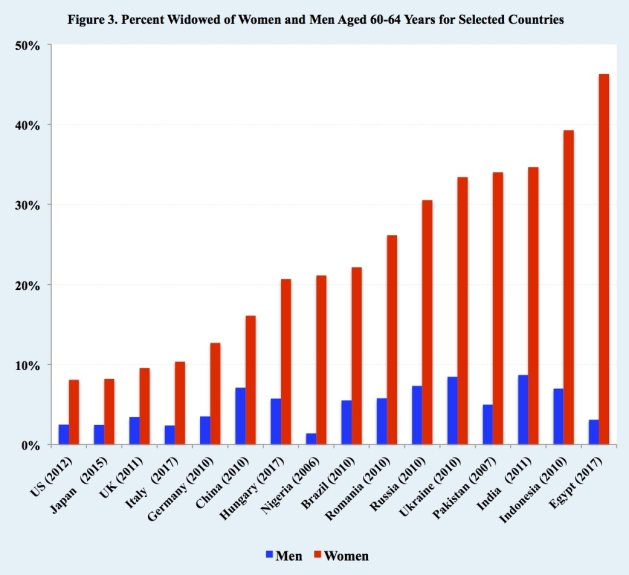

While general widowhood rates for women and men provide an indication of its prevalence in a country, rates by age offer more comparable information about differences among countries. Examination of the age group 60 to 64 years, for example, provides insight into the transition to widowhood among elderly women and men.

While one out of ten women aged 60 to 64 years are widows in Italy, Japan United Kingdom and the United States, no less than one out of three women in the same age group are widows in Egypt, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Ukraine (Figure 3).

Also as observed earlier, the rates of widowhood for men across age groups are a fraction of those for women. Among the age group 60 to 64 years, for example, less than one in ten men are widowed in most countries, with many instances of less than one in twenty men widowed.

Worldwide widowed women are less likely to remarry than widowed men. In the United States, for example, ten times as many widowers as widows over age 65 years remarry, though there are fewer older men than older women.

Although remarriage may be less frequent in developing countries for demographic as well as cultural reasons, widowers remarry more often than widows. In India, for example, the percentage of men who remarry is twice that of women.

In virtually every society the transition to widowhood is widely recognized as an inevitable outcome for married and partnered couples. Nevertheless, most people are not at all prepared for the emotional stresses, personal upheavals and other challenges resulting from widowhood.

Certainly, one cannot be fully prepared for the death of one's spouse or partner, which is ranked as number one on the Holmes/Rahe stress scale of adverse life events. However, couples can take a number of steps that can help mitigate many of the difficult consequences of widowhood.

To start with, couples should not view widowhood as an unmentionable subject. Husbands and wives need to talk candidly and plan explicitly for the transition into widowhood. The discussions need to cover a broad range of issues, including a will, inheritance, funeral wishes, estate planning, finances, properties, official documents, personal information, family matters, relations with in-laws and future living arrangements.

Those discussions will no doubt be difficult and uncomfortable, especially in traditional settings where rigid norms and cultural prohibitions severely limit discussing and planning for the future death of one's spouse.

Nevertheless, couples need to be prepared for the death of a spouse or partner and its onerous consequences well before it happens.

It is also important for couples, especially women, to recognize the near certain significant life changes that occur after a spouse passes away. Additional responsibilities, family and in-law relationships, friendships, time use, financial matters, loneliness, childrearing, housing, relocation and life style are just a few of the many challenging areas faced by widowed persons. Given the new and daunting circumstances facing the surviving spouse, going slow and postponing making major decisions is strongly advised.

Some couples may choose to read about widowhood and how to deal with the resulting grief and sorrow as well as how best to handle practical matters. Others may prefer to talk with family members and close friends about how to prepare for coping with widowhood.

Grief, bereavement, shock, depression and even guilt have been found to dominate the first twelve months after a spouse's death, greatly impairing meaningful decision-making, undermining mental stability and threatening overall health.

The sadness, anxiety and loneliness over the loss of a spouse or life partner typically have detrimental effects on the psychological, social, physical and economic wellbeing of the surviving spouse, especially among the elderly, for the rest of their life.

Those effects differ somewhat by gender. Widowers, for example, may become more depressed and withdrawn than widows because men typically do not have a strong enough social support network of friends that women tend to develop.

In contrast, widows tend to encounter greater financial difficulties and economic hardships than widowers, particularly in societies where wives have little status or entitlement except in relation to their husbands. In many instances, the road to poverty, indignation , discrimination and abuse for widows begins after their spouse or partner dies.

When a spouse passes away, the widowed person has an increased risk of dying over the next few months, often referred to as the widowhood effect. Elderly widows and widowers living on their own, in particular, are likely to benefit from an active and strong support network of family and friends to help counteract the grief, anxiety and loneliness of losing a spouse. Also, counseling, both individual and group, may be helpful for the recently widowed.

It is increasingly evident that the plight of widowed persons is not only a moral issue, but also one that has systemic implications for societies that threaten economic and social stability.

Widowhood remains an important risk factor for transition into poverty. Also in a in a rapidly aging world, widowhood has become an even more critical concern with more people, especially women making up the large majority, outliving their spouses by many years.

In addition to ensuring the fundamental rights and dignity of widowed persons, governments should develop appropriate policies and programs to prepare and assist couples and their families for the difficult but inevitable transition to widowhood.

Complementing state and community activities, non-governmental organizations, such as the Loomba Foundation, Global Fund for Widows, and Widow Rights International, should continue their educational and advocacy efforts on the challenges and plight of widowhood.

Finally, planning for widowhood is an important and prudent thing that all couples need to do. The chances of avoiding widowhood in a good marriage or long-term partnership are close to nil.

Discussing and preparing for widowhood will certainly not reduce the grief and loneliness following the death of a spouse or partner. However, being unprepared for widowhood exacerbates bereavement, gives rise to unnecessary stresses and greatly complicates a surviving spouse's remaining years of life.

*Joseph Chamie, a former director of the United Nations Population Division, is currently an independent consulting demographer.

© Inter Press Service (2020) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues