Nepal Struggles to Preserve Its Indigenous Languages as Those Speaking Them Dwindle

KATMANDU, Feb 03 (IPS) - At last count Nepal had 129 spoken languages, but even as new ones are identified, others are becoming extinct. At least 24 of the languages and dialects spoken in Nepal are ‘endangered’, and the next ones on the verge of disappearing are Dura, Kusunda, and Tillung, each of which have only one speaker left.

“It will not surprise me if these three languages will be the next to go. With no one left to speak, we will not be able to save them,” says Lok Bahadur Lopchan of the Language Commission of Nepal, which is entrusted with preserving Nepal’s linguistic diversity.

If a language is spoken by less than 1,000 people, it is categorised as ‘endangered’. Lopchan predicts that over 37 more languages spoken in Nepal are in that category and likely to disappear in the next ten years.

According to the Language Commission of Nepal‘s 2019 annual report the languages most commonly spoken in the country are Nepali, Maithili, Bhojpuri, Tharu, Tamang, Nepal Bhasa, Bajjika, Magar, Doteli and Urdu, in that order.

But just as there are languages disappearing, new ones that had never been recognised are being found in far flung parts of the country, like Rana Tharu which is spoken in the western Tarai, Narphu in a remote valley in Manang, Tsum in the Tsum Valley of Upper Gorkha, Nubri Larke in the Manaslu region, Poike and Syarke.

“It is fortunate that these languages have been identified, but it is unfortunate they are spoken by very few people, and could very soon die out,” says Lopchan, who adds that every two weeks, an indigenous language goes extinct somewhere in the world.

Even those that are among the top ten most spoken in Nepal are losing their first language status. Parents insist on proficiency in Nepali or English in school to ensure good job prospects for their children. And even since King Mahendra’s reign, the state has pushed Nepali as the lingua franca to the detriment of other national languages.

Supral Raj Joshi, 29, is a voice actor and grew up speaking Nepal Bhasa at home. But from primary school onwards, it was Nepali and English only in class, and he soon forgot his mother tongue. Speaking Nepali with his family, it suddenly struck him how much of his culture he had lost with the language.

“The loss of Nepal’s languages is the result of deliberate state policy, our linguistic heritage was swept away to promote a national character,” says Joshi.

King Mahendra instituted measures to create a unified Nepali identity through dress, language, and even dismantled democracy and instituted the partyless Panchayat system that he said “suited the Nepali soil”.

Experts say that the decision enforcing the idea of nationalism through one language restricted indigenous communities to speak their ancestral tongue.

“The dominant class made its language the national language, and in doing so other languages suffered collateral damage,” says Rajendra Dahal, Editor of Shikshak magazine. “The end of a language is not just a loss for a community, but for the country and the world.”

At the Language Commission of Nepal, there is a sense of urgency to save the three languages that each have only one speaker left. It has partnered with 45-year-old Kamala Kusunda, the only living person in the world who speaks Kusunda. She now runs a small private school in Dang to teach the language to over 20 students.

“If I die, then my mother language dies with me too. I had to revive this language for its value to our people, and the hope of keeping our ancestral language alive,” Kamal Kusunda told Nepali Times over the phone.

Muktinath Ghimire in Lamjung has a similar task. As the only remaining speaker of Dura, he is preparing to start a school to teach the language to others in the community. “We can’t let this language die,” he says.

Other languages like Tsum, more recently identified as distinct dialects, were already endangered by the time they were identified as being uniquely different.

“Older people in Tsum Valley exclusively speak Tsum, but the younger generation is losing the language,” says Wangchuk Rapten Lama, a fluent Tsum speaker himself who is working to expand its use by introducing the language to children through cultural activities.

Canada-based linguistic anthropologist Mark Turin worked with the Thangmi in Dolakha and Sindhupalchok to document their endangered language.

“To speak of linguists saving languages is just as ludicrous as suggesting that Apps and digital technologies save language,” he says. “Neither is true, and field linguistics is still dominated by quite colonial and extractivist models of knowledge production.”

He says speakers of indigenous languages like Thangmi deserve the recognition as they work tirelessly to reclaim, rejuvenate and revive their ancestral languages, often in the face of considerable opposition.

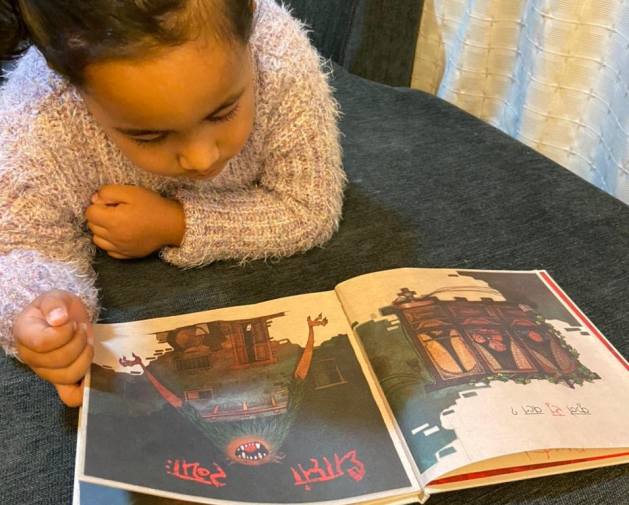

“Indigenous youth in these communities are now creating domains of use for ancestral languages to thrive once again, in print, online and on air. This is the true work of language revitalisation and reclamation, and it deserves wider recognition,” Turin adds.

After Nepal went into the federal mode, it was expected that schools across the country would teach regional languages. Article 31 of the Constitution says: ‘Every Nepali community living in Nepal shall have the right to acquire education in their mother tongue up to the secondary level, and the right to open and run schools and educational institutions as provided for by law.’

The Curriculum Development Centre along with rural municipalities introduced a ‘local curriculum’ bearing 100 points. For instance, Bhaktapur and Gokarna municipalities have curricula designed to teach students about their own municipalities. While some schools offer mother tongues as an option, a majority choose the ‘local curriculum’.

In October 2020, Kathmandu Mayor Bidya Sundar Shakya made it mandatory for schools to teach Nepal Bhasa from Grade 1-8. But there was mixed reaction from parents, with many feeling it would burden the students and their Nepali and English would suffer.

“We have tried offering students formal classes on Nepal Bhasa for many years, but there was not much interest from guardians even though we know children thrive when they learn new languages,” says Jyoti Man Sherchan, former Principal of Malpi International School, who introduced a Thakali language club in the school.

“Parents are more interested in their children being proficient in English or Mandarin. Change is possible only if the government intervenes and provides resources and training to teach our own mother tongues,” says Sherchan.

However, there are limitations in residential schools where students come from all over Nepal. It is impossible to make everyone speak different languages.

Province 2 is different because the Tarai districts are the most multilingual in the country. In Birganj, for example, most people speak Maithili and Bhojpuri, and they also speak Hindi, Nepali or English.

“Although schools here do not teach ancestral languages, the majority of children continue to speak Maithili and Bhojpuri at home,” explains writer Chandra Kishore. “In my school English and Nepali were taught, but the medium language for explaining those languages was Maithili.

Languages stop evolving once people stop conversing in them. Ancestral languages are also needed to root a people in their heritage and give a distinct identity. This is becoming more and more difficult all over the world with globalisation and the Internet.

“My little children only speak English,” says Saraswati Lama who is married to a Rai, and works for a non-profit in Kathmandu. “My daughter learned it from YouTube and she taught it to her younger brother.” Neither Lama, nor her husband speak their own mother tongues, and use Nepali to speak with one another.

But these days, it is in the Nepali diaspora that the country’s linguistic heritage seems to be valued more. Sujan Shrestha was born in Kathmandu but moved to the US while he was in high school. Now a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, he says his wife and children only speak English and Nepal Bhasa, and no Nepali.

“Nepal Bhasa gives the kids an identity, and connects them to the extended family, especially their grandparents. It is about teaching our kids cultural sensitivity and open-mindedness towards other cultures and people.”

This story was originally published by The Nepali Times

© Inter Press Service (2021) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues