How Technology Can Promote Multilingualism & How it Cannot

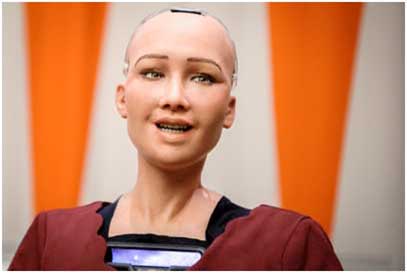

GENEVA, Feb 23 (IPS) - Some of you may remember Sophia, the talking robot. In 2017 and 2018 she toured UN meetings and TV studios, wowing audiences with her thoughts on the future of technology and seemingly engaging in conversations with UN deputy chief, Amina Mohammed and British broadcaster, Piers Morgan.

The UN declared her an innovation champion, Elle magazine put her on their cover and Saudi Arabia granted her citizenship, a hat trick of “firsts” for a robot.

Many were impressed by her human qualities. Yet her ability to follow gazes and respond to questions masked the human input required to provide a lifelike experience and pithy one-liners. Those interviewing her reported (https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-42616687) having to send questions in advance.

And while Sophia certainly created an important debate on the future of artificial intelligence, even her makers, following much criticism, admitted (https://www.theverge.com/2017/11/10/16617092/sophia-the-robot-citizen-ai-hanson-robotics-ben-goertzel) that people had been too quick to overestimate her technological ability. Behind the wishful thinking, she was more airline customer service chatbot than human.

Yet while Sophia appears to have disappeared from public view, perhaps as a result of Covid-19 (which also appears to have diminished our faith in airline customer service chatbots), digital diplomacy, as we discovered during this year’s International Mother Tongue Day, isn’t immune to technological overhype.

Next month the UN will test a new virtual interpretation system at the 14th Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice to be held in Kyoto. A number of delegates will be travelling there, but the UN’s interpreters in Vienna and New York, that would have normally joined the conference, will instead be staying at home.

Working early morning and late night shifts they will interpret the meeting’s negotiations into the six UN languages over the internet. Think of it as being in a Teams or Zoom meeting. Not only do you have to try and understand exactly what is being said, but you also need to interpret it into another language and feed it back down the same line.

The biggest challenge won’t be “you’re on mute,” but the poor sound quality.

Experience from using the system during lockdown, when there was no other choice, showed how poor sound quality and failing connections made the work more daunting, as interpreters need a higher quality of sound than a normal listener to perform their job correctly.

Interpreters reported acute acoustic shock, tinnitus, headaches, and nausea. The poor sound quality is because the platforms currently on the market compress the sound to push the back and forth of languages down the line at the same time. None of the systems are ISO-compliant.

The UN is not alone with these problems.

An article (https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/virtual-parliament-interpreters-injuries_ca_5eb55c99c5b6a67335415963) on the Canadian parliament, which operates in English and French, noted that, “coping with iffy audio quality, occasional feedback loops, new technology and MPs who speak too quickly has resulted in a steep increase in interpreters reporting workplace injuries”.

Assumptions about the powers of technology have also affected the UN’s translators. Following the introduction of a new computer-assisted translation tool, they have been told to increase their daily productivity target from 5 pages of often dense technical text, to 5.8.

The software has been hyped as a google translate on steroids. But a recent survey of its users showed that view was far from shared.

While recognizing its benefits, eighty percent of translators said they would not be able to meet the new productivity targets while maintaining minimum standards of quality. One said the software was “often slow and time consuming, rather than time-saving, and its role is way overrated.”

Another commented that rewriting poor machine translations demanded more time than translating from scratch. Several noted that computer-assisted translations could not compensate an overall decline in the quality of the original texts that translators received.

This year’s International Mother Tongue Day was devoted to multilingualism.

But two years ago, the UN General Assembly rightly noted that “multilingualism promotes unity in diversity and international understanding, tolerance and dialogue”, and recognized its contribution in “promoting international peace and security”.

Technology has an important role in promoting communications between linguistic groups, and has already made an important difference. But as with Sophia, this year we need to be as much aware of what it can do as what it can’t.

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS New UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2021) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues