Afghan Refugees Fear Return as Pakistan Cracks Down on Migrants

KARACHI, Feb 01 (IPS) - “If I return to Afghanistan, the Taliban will kill me; I’m prepared to stay in a prison in Karachi than face those ruthless people,” said 24-year-old Afghan refugee, Sabrina Zalmai*, referring to the recent crackdown on hundreds of Afghans residing without proper documents in the metropolis, who are being arrested and then deported back to Afghanistan.

Having taken refuge in Pakistan for almost a year without a visa, she said she was feeling extremely unsafe. “We are trying to remain as invisible as possible,” she said.

But, said 45-year-old Naghma Ziauddin*, a former broadcast journalist working in Kabul, and having fled to Karachi, living under the radar, illegally, in the city was difficult. If arrested and deported, she said, she would instantly be recognized since she had been “very vocal in my hatred for the Taliban, and they know my voice.”

She, her husband, two sons, and a sick daughter-in-law came to Karachi in March 2022. “If they put us behind bars, how will we take care of my daughter-in-law?” she said, adding: “Because of the recent arrests, we have become caged in our home. I hardly go out; I am always anxious about being apprehended when I take my daughter-in-law to see the doctor for her monthly check-up.”

According to official reports, about 250,000 Afghans have fled to Pakistan after the Taliban seized power in August 2021.

But the amnesty extended to those fleeing Afghanistan and entering Pakistan with valid visas that have expired, terminated in December 2022.

To renew their visas, they have to re-enter Afghanistan, which they still find a dangerous place.

A majority of those who fled feared they would find themselves in the crosshairs of the Taliban. These included soldiers, judges, journalists, human rights defenders, and those whom the Taliban despised, the Shia Hazaras, the LGBTQIA+, and those who were musicians and singers. The economic immigrants who were without work in Afghanistan were also among the refugees.

Ziauddin finds deportations “very inhuman”.

Not only is it inhuman, said Umer Ijaz Gilani, an Islamabad-based lawyer, it is a violation of the non-refoulement (forcibly returning refugees or asylum seekers where they may be persecuted) principle. Acting on behalf of 100 Afghan human rights defenders seeking asylum, he has urged the government’s National Commission on Human Rights to direct state authorities not to deport them. “We may have to take them to the court otherwise,” he told IPS in a phone interview.

According to Moniza Kakar, a Karachi-based young human rights lawyer, Afghan refugees are being arrested across Pakistan. “They get deported immediately in other provinces, but in Sindh, the arrested Afghans are put behind bars for months, treated badly in prisons, fined, and then deported,” she said.

Kakar is helping in the release of the Afghan refugees in Sindh. “So far, of the 1,400 arrested (including 200 women and 350 children), 600 have been released and deported,” she told IPS.

“If a person lives illegally in any country, the government takes action and deals with them according to the law,” Sindh Information Minister Sharjeel Memon said, justifying the arrests. “Nobody has been sentenced to jail for more than two months,” he added. He also denied that children were put behind bars.

Kakar said because Pakistan had not adopted the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, “which stops states from punishing people who enter a country illegally”, it is able to invoke the domestic Foreigners Act 1946 to use against Afghans residing in Pakistan illegally, to punish and deport them.

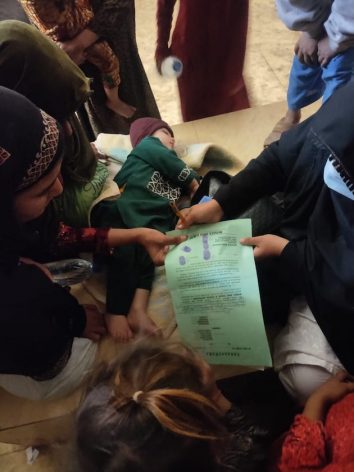

Of the imprisoned Afghans, Kakar said, nearly 400 had been arrested wrongfully as they had valid documents that allowed them to stay in Pakistan. They remained incarcerated for months till their cases were heard.

“Some Afghans arrested in Jacobabad have been sentenced to as much as six months rigorous imprisonment and a fine of Rs 5,000 imposed on all males, and Rs 1,000 each on all minors and females,” she said, contradicting Memon’s statement to media. “Why were minors fined when the government claims they were not offenders or imprisoned?” she asked.

Kakar said because Pakistan had not adopted the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, “which stops states from punishing people who enter a country illegally”, it is able to invoke the domestic Foreigners Act 1946 to use against Afghans residing in Pakistan illegally, to punish and deport them.

Amnesty International has urged the Pakistani government to stop the deportations and extend support to the refugees so they can live with dignity and free of fear of being returned to Afghanistan. In a letter to Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, Agnes Callamard, secretary general of Amnesty International, said she found it alarming to note the country lacked national legislation for the protection of refugees and asylum seekers.

Pakistan may not have signed the international refuge protocol, but, argued Lahore-based Sikander Shah, who teaches at the law school at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, there were several international human rights conventions that Pakistan had adopted, like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, that can be “turned to, to help the hapless refugees”.

“My experience has been that the judges in Sindh do not empathize with the Afghan refugees,” pointed out Kakar. “In fact, one judge said in the open court that the refugees did not deserve to be looked at from a humanitarian lens; that they were criminals who were involved in terrorist activities in our country,” said the young rights activist bemoaning the open hostility prevalent not just among other segments of society, but even her own legal fraternity.

She also said the Afghans were especially ill-treated both by prison authorities and the inmates. “They complain of being lugged with more than their share of work and not always provided with meals,” said Kakar.

Many say they face constant discrimination.

Armineh Nasar* 21, another refugee, who came to Karachi last year, in December 2021, with her mother and three siblings, said she had experienced much suspicion. “I have witnessed how Pakistani mothers pull away their children when they find out their kids are playing with Afghan kids. I’ve heard them say, we are terrorists,” she said.

Before the Taliban took over Kabul, Zalmai was working in Kabul in a nongovernmental organization. But the reason she would find herself on the wrong side of the Taliban if she were deported was that, like Ziauddin, she had been “very vocal in my dislike of the Taliban, and they know who I am.” She fled with her grandmother in January 2022 after her family got hold of a hitlist of Taliban which had her name on it as well.

With a BA in economics, her dream of opening a boutique in Kabul’s upscale market has been dashed. “Right now, I work as a domestic help, sweeping floors, earning up to Rs 300 (USD 1.30 cents) for half a day’s work,” because she cannot find any office work as it would require her to show an identification card. “I had never done this kind of work even at home as I was either studying or working outside. “We are a family of seven; I’m the eldest, and I was the main bread earner of my family, earning Afghani 15,000 (USD 166) per month,” she told IPS. Her father, a security guard in an office, earned less.

Like the other two, Nasar, too, cannot find work, so she keeps hopping from one job to the other till the issue of documents comes up. “I’ve worked in an office and in a supermarket, each lasting three months, and then had to leave as I was unable to show any identity card.” Having studied till 12 grade in Kabul, she wanted to enroll in higher studies. “But the university administration wants to see a refugee card before giving me admission. I’ve missed a year because of that!” said Nasar, who wants to study computer sciences and enter the profession of banking.

But it is not just that they cannot work; without documentation, Afghans cannot access housing or open bank accounts (to be able to receive money). They also cannot obtain a SIM card or seek medical treatment at a government facility.

With no one in her family able to earn, Ziauddin said she was worried the family would soon run out of money. The cash they had after selling her jewelry and household items to flee to Pakistan is drying up fast, as are all their savings.

“I am under a lot of anxiety that has caused my blood pressure to rise,” said Ziauddin. Her doctor had suggested she begin walking as a form of exercise, which she did, but she gave it up after she got robbed last month.

“If only the UNHCR could provide us with the documents stating we are refugees, we would not face so many problems,” she said.

But it seems even the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ hands are tied.

Since 2021, the UNHCR has been in discussion with the government on measures and mechanisms to support vulnerable Afghans. “Regrettably, no progress has been made,” said UNHCR spokesperson Qaiser Khan Afridi.

He said the refugee agency was ready to work with the government of Pakistan in identifying Afghans in need of protection and to seek solutions to their plight. But the latter has yet to agree to recognize the newly arriving Afghans as refugees. “It does, however, allow Afghans in possession of a valid passport and visa to cross into Pakistan; the online visa application process is also available to those with passports.”

In addition, said Afridi, in line with its mandate, the UNHCR strives to find durable solutions for refugees. “But the realization of such solutions is beyond its control.” It all depends on countries to offer third-country resettlement opportunities or to allow refugees to naturalize as citizens in the country where they sought asylum. “Resettlement, unfortunately, cannot be available for the entire refugee population as the opportunities are limited,” he agreed but said the refugee agency was urging RST (Refugee Status Determination) countries (like Pakistan) to increase the resettlement quotas.

*Names have been changed to protect their identity. IPS UN Bureau Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues