Myanmars Forgotten War Lurches Deeper into Horror

KAYIN STATE, Myanmar, Apr 17 (IPS) - Food is passed around a campfire, and a guitar strums as cool night air tumbles down mountain cliffs, relieving the jungle of its heat.

A dozen or so young Myanmar activists – some having just travelled long distances evading military checkpoints, others already living in exile – have come together in a jungle camp for a training course with a difference. Instead of armed combat, their chosen role is enabling the overthrow of the military junta through non-violent means.

Conversations are animated, with talk of federal democracy and creating a country that would also give political space and freedom to ethnic minorities. They are joined by soldiers of the rebel Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) protecting the camp deep in southeastern Kayin State.

The peaceful setting of the camp belies the horrors of the civil war beyond the mountains that is breaking Myanmar apart. The generals who overthrew a democratically elected government and seized power in 2021 are increasingly responding to a national uprising by waging terror on civilians it calls “terrorists” in an attempt to break their support for armed insurgents.

On April 11, the military carried out what is believed to be the deadliest attack of the civil war so far, using air strikes and a helicopter gunship on a village ceremony organised by the parallel and underground National Unity Government (NUG) in Sagaing Region.

At least 165 people, including 27 women and 19 children, some performing dances, were killed, according to the NUG. The regime says it was attacking the NUG’s People’s Defence Forces.

Over the past two years, artillery and bombing raids using aircraft supplied by China and Russia have targeted schools, IDP camps, hospitals, mosques, Buddhist temples and Christian churches across the country. Tens of thousands of houses have been torched, and more than 1.3 million people displaced since the 2021 coup, according to UN estimates.

The barbarity defies belief. In February, a unit of some 150 soldiers known as the Ogre Column were dropped by helicopter in Sagaing and went on a marauding killing spree that lasted weeks. Scores of villagers were killed. Women were raped and shot. Men and boys were beheaded, disembowelled and dismembered.

Truth about massacres in wars gone by took months or even years to fully emerge, but in this modern era of mobile phones and social media, the grim evidence is transmitted by survivors within a day or so.

Kyaw Soe Win, a veteran activist with the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), which carefully documents civilian deaths, arrests and extra-judicial killings, shows IPS a picture he has just received on his phone of a man in Sagaing, disembowelled and his organs taken out.

Why do they do this? “It is to spread fear and terror,” he says.

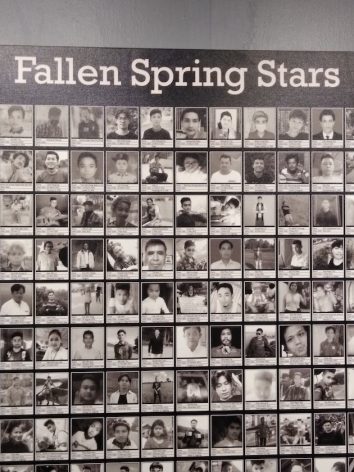

AAPP, now based in the border town of Mae Sot just inside Thailand, has an exhibition dedicated to victims of successive uprisings against military rule since protests against the first post-independence coup in 1962. Rows of faces and names stare out from the walls, including pictures of some 30 civilians – among them two Save the Children charity workers – who were tortured and burned alive in what is now known as the 2021 Christmas Eve Massacre in Kayah State.

“This chapter is different,” Kyaw Soe Win, a former political prisoner, says of the present conflict. “The situation is getting worse and worse. The numbers of political prisoners and fatalities and houses torched are far higher. The junta is oppressing the people and is even more brutal than before.”

Sky, a resistance fighter and writer, who uses a nom de guerre, explains in a Mae Sot bar how the insurgency is also very different this time.

“After the 1988 student uprising, it took me three years to get an AK-47 and 300 bullets. Now it is much quicker. Now we are getting modified AK-47s through the Wa. They call it a Wa-AK,” he laughs, referring to an autonomous border area run by the heavily armed United Wa State Party. Their one-party narco-state on the border with China stays out of the war but makes money from both sides.

“China systematically eroded history after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, but after the 1988 protests in Myanmar, we still have the whispered stories. This generation knows what is right and wrong,” said Sky.

Despite what the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights recently called its “scorched earth policy”, the regime is steadily losing this war in terms of territory and military casualties.

“The military is in a very, very difficult situation which is only getting worse,” says Matthew Arnold, an independent policy analyst on Myanmar with previous conflict experience in Afghanistan and Sudan. He says the regime’s forces are “atomised” and “bleeding out in a war of attrition”. In some towns, they are pinned down in police stations and barracks and cannot be reinforced or resupplied for months on end.

Because it cannot move freely on the ground over the vast distances to maintain its outposts and impose its authority, the junta is resorting increasingly to air strikes and artillery against civilian populations.

Sagaing and the neighbouring region of Magwe are crucial conflict areas. Covering an area bigger than England, they are known as the heartland of the Bamar majority and had been, for decades, a fertile recruiting ground for the Bamar-dominated military. But no more.

“There are very few areas of Sagaing where they are not fighting on a regular basis. The junta was hit all over the place in February in Sagaing and Magwe,” says Arnold, who credits resistance forces moving rapidly “from muskets to drones and IEDS” (improvised explosive devices) in inflicting heavy losses.

Vulnerable in more remote areas in Chin State in the west and areas of the southeast, the military’s pullback is expected to accelerate as the monsoons come.

Thantlang in Chin State, near the border with India, was the first large town to fall to the rebels, although the junta’s bombing raids and artillery made sure that little was left standing. With no air defences, the resistance knows well that if it takes full control of more urban areas, then they are inviting disaster upon the civilian population.

Myanmar is, in effect, fragmenting.

The regime has a firm grip on the big cities of Yangon, Mandalay and the capital Naypyitaw – where residents say life is bustling and returning to some kind of ‘normal’ with even the makings of a property boom. But beyond, its real control is tenuous and weakening.

Fighting a war on many fronts, the regime is trying to follow its practised divide-and-rule tactics of cutting deals and ceasefire pacts with various ethnic armed groups, aided to some extent by China’s influence in border areas.

But major ethnic groups in most of the frontier states, such as the KNLA, which has been fighting the world’s longest civil war since 1949, are successfully resisting. A ceasefire with the mostly Buddhist Arakan Army also looks fragile in the western state of Rakhine, where in 2017, the military forced over 700,000 Muslim Rohingya into Bangladesh in a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing that has brought charges of genocide against Myanmar in the International Court of Justice.

“Sadly, a prolonged fragmentation is a possibility, but we must accept that has been a possibility in Myanmar since before the coup of 1962,” David Gum Awng, deputy minister for international cooperation for the NUG shadow administration, tells IPS.

“It is natural and unsurprising that EAOs (ethnic armed organisations) are consolidating gains, but the question is what these EAOs plan to do with their territory if and when the democratic forces win,” he adds.

The NUG, he says, aims to rid Myanmar of the “abusive and criminal military dictatorship and along with it the military's obsession with centralised Bamar-Buddhist nationalist rule”, to be replaced by a democratic federal system offering “ethnic minorities genuine self-determination” through negotiations.

This significant shift in policy also extends to recognising and reaching out to the Rohingya, with the NUG promising justice and accountability for crimes committed against them by the military, a path towards citizenship, and peaceful repatriation for refugees.

Although the NUG is built around remnants of the old guard of the National League for Democracy government ousted in the 2021 coup, its stated intentions have set it apart from the Bamar nationalist leanings of Aung San Suu Kyi, its 77-year-old former leader now held by the junta in solitary confinement.

Strengthening but still, difficult ties between the self-proclaimed NUG and the ethnic armed groups are particularly worrying for China. Myanmar’s giant neighbour sees a threat to its long-term strategy of dominating the ethnic groups along its border while keeping Western powers out of a pliant Myanmar with the goal of developing massive infrastructure projects and a secure gateway to the Indian Ocean.

Even though it enjoyed favourable relations with Aung San Suu Kyi, China is keeping the NUG at a cold arm’s length while propping up the junta with weaponry and diplomatic protection at the UN. India’s tacit backing for the regime has facilitated its own strategic investments.

Much of the rest of Asia, including democracies like Japan and South Korea, are also working to protect their own interests in Myanmar while hoping that engagement with the regime will lead to a negotiated settlement of the war. UN agencies and the INGO aid industry also maintain a presence, mostly ineffectual, in junta-controlled Yangon.

This perceived complicity angers the Burmese diaspora, which is busily raising money for aid and weapons for the resistance. Notions of a negotiated settlement with General Min Aung Hlaing’s State Administration Council, as the junta calls itself, are far from the minds of those waging their “forgotten war”.

“Thai generals are brothers with the Myanmar military. Singapore banks hold their money. The Burmese feel forgotten,” said one US-based doctor, speaking in Bangkok after taking medical aid to the border.

While recognising that the West’s attention and resources are focused on the overriding goal of defeating Russia in Ukraine, the resistance did receive a significant boost last December with the US Burma Act passed by Congress.

The act authorises the Biden administration to extend non-lethal aid to “support the people of Burma in their struggle for democracy, freedom, human rights, and justice.” It explicitly mentions the NUG, although not ethnic armed groups.

Some Washington-based analysts argue that the legislation does not mark a major US policy shift, but diplomats and experts in the region see it as a highly significant step towards endorsing the NUG and the wider resistance movement.

“The US is now saying it wants the resistance to win and has fundamentally shifted the narrative. This is why China is getting worried. Beijing is focused on the discourse of talks and the peace process,” commented one expert in Bangkok who asked not to be named.

“There won’t be lethal assistance. The US doesn’t want to be involved in another war now. But there will be more public and diplomatic support of the resistance and pushing other actors not to engage with the junta,” he added.

David Gum Aung of the NUG is more cautious, calling the Burma Act “a significant piece of legislation” which makes funds available and opens the door to more sanctions against the regime while “recognising” the NUG.

“We can view the Burma Act as a very important document symbolically but less potent practically. Its symbolic value stems largely from the fact that it outlines that the US views the SAC and their caretaker government as illegitimate and does not recognize their authority, their right to represent Myanmar or their justification for the coup.”

“We are still sorely in need of all manner of aid, from humanitarian to strategic… but we cannot fall into the trap of assuming that everything the Act makes possible will eventuate,” he said.

Thinzar Shunlei Yi, a democracy and youth activist who led anti-coup protests in Yangon and is now in exile, stresses that the broad-based and non-violent Civil Disobedience Movement remains the “backbone of the revolution”.

Success, she says, will mean the surrender of the junta, with the people defining what happens to the perpetrators of crimes, whether to be put on trial in domestic courts or through international mechanisms. For her, it also means a social revolution that will tackle “patriarchy, hegemony, racism etc”.

Kyaw Soe Win of the AAPP, whose grisly routine is to scroll through fresh images of the dead, says war criminals must be prosecuted to achieve national reconciliation.

“We need justice for the survivors and victims,” he says. “Without justice, there can be no reconciliation. There was never any justice before, only impunity through the decades. No action was ever taken.”

AAPP has so far documented over 17,000 political prisoners still in detention and the deaths of over 3,100 civilians since the coup, although it knows the actual toll is much higher.

Nicholas Koumjian, head of the UN-authorised Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar which is working with AAPP, says credible evidence had been collected of an “array of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, rape, torture, unlawful imprisonment, and deportation or forcible transfer”.

Back in the jungle resistance camp, the young activists gather near caves that act as air raid shelters and talk of a future without military rule that will necessitate total reform of the armed forces. Among the group, one was severely tortured in prison, one shot in the leg during street protests and a mother who had to leave her child behind.

The annual New Year festival of Thingyan is approaching, and they sing popular songs of love and separation and a homecoming they know may be years away.

AAPP is working with the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar to collect and preserve evidence of crimes against international law committed since 2011 to expedite future criminal proceedings. Nicholas Koumjian, head of the IIMM, said on the second anniversary of the coup that credible evidence had been collected of an “array of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, rape, torture, unlawful imprisonment, and deportation or forcible transfer.”

IPS UN Bureau Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues