Trafficking in the Sahel: Smugglers ‘will take you anywhere’

Call a friend with a connection, get a passport in 24 hours, and hand over some cash. That is what it takes to flee the fragile Sahel region of Africa, where smuggling networks exploit the desperation of people, leading in some cases to such deadly disasters as the recent shipwreck off the coast of Greece.

In this feature, part of a series exploring trafficking in the Sahel, UN News focuses on migrant smuggling.

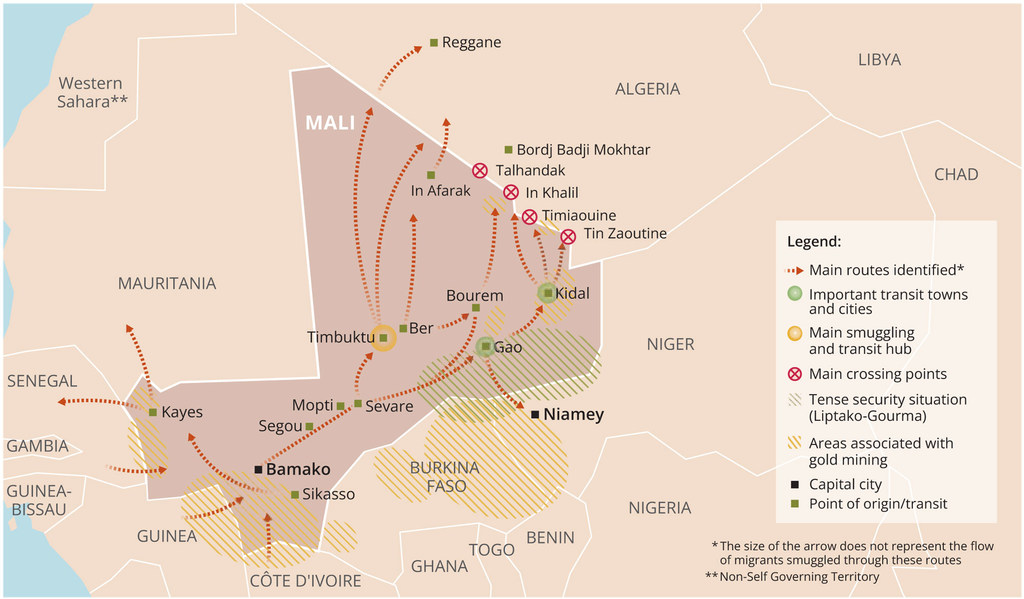

Migrant smugglers have been reaping rich dividends over the past decade in the Sahel, where armed violence, terrorist attacks, and climate shocks have displaced three million people and triggered growing numbers of others to flee, according to a new threat assessment report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

External threats like the crisis in Sudan are creating a “snowball effect” on the region, Mar Dieye, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Coordinator in the Sahel, told UN News.

“Not stopping this fire that started from Sudan and then spilled over in Chad and other regions could be an international disaster that will trigger a lot of more migrants,” said Mr. Dieye, who also heads the UN Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS).

‘We will take you anywhere’

Right now, Mr. Dieye said, most trafficking occurs at porous ungoverned border areas where the State is “extremely weak”.

The latest UNODC report identified other drivers alongside solutions buttressed by interviews with migrants and the criminals smuggling them, who revealed how the cross-border crime is unfolding in towns across the Sahel.

Many interviewees said smugglers were cheaper and quicker than regular migration, the report found. In Mali, where monthly income averages $74, a passport costs nearly $100.

In Niger, a key informant said authorities can take three to four months to process official documentation.

“But with us, if you want, we will take you anywhere,” the informant said.

If a passport is needed, a smuggler in Mali said in the report, “I will have it in 24 hours.”

‘Cash-cash’ partnerships

The report pointed to corruption as both a motivator to use smugglers and a key enabler for the crime.

Migrant smugglers could earn around $1,400 a month, or 20 times the average income in Burkina Faso, according to UNODC.

“Lucky smugglers” can earn as much as $15,000 to $20,000 per month, a smuggler in Niger said in the report.

The degree of collaboration with public officials is so entrenched, a smuggler in Mali explained, that he “has no fear of punishment from the authorities”, according to the report.

“I have never been worried by the authorities,” the smuggler said. “We are in a cash-cash partnership.”

Recalling instances when arriving at police checkpoints, a key informant interviewed in Niger shared his experience.

“You go to see them and give them their envelope, but, if you don’t know anyone in the team, you are obliged to take the migrants out and put them on motorcycles to bypass the checkpoint,” the informant added.

Ever greater risks

Increased demand from men, women, and children seeking to escape worsening violence and the consequent rising food insecurity has fuelled the cross-border crime, according to UNODC.

Since the discovery in 2012 of gold lacing the region, UNODC said research points to mining sites, where women are trafficked for sexual exploitation, and men are forced into indentured labour.

Smuggling routes have also become more clandestine and diverse in attempts to evade growing efforts by security forces, exposing refugees and migrants to even greater risks and dangers, according to the agency.

Stemming the flow

All the Sahel countries except Chad are party to the Protocol against smuggling of migrants, which supplements the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, and have dedicated laws that are making progress, the report stated.

On the ground, operations are succeeding, UNODC reported. Among many examples cited in the report, a 2018 operation saw Nigerien police officers arrest ringleaders and dismantle a highly organized network suspected of having smuggled thousands of migrants to Spain, including through the Niger, Libya, and Algeria.

To build on these achievements, UNODC recommended actions States can take to tackle migrant smuggling, address the root causes, combat corruption, and create local job opportunities. The agency also suggested that counter-smuggling policies include development and human rights approaches.

Uprooting the causes

For many UN agencies and Sahelian nations, cooperation is key. Ongoing International Office for Migration (IOM) efforts include boosting livelihoods for returning migrants and forging new partnerships, including a recent agreement with the G5 Sahel Force, a multinational mission aimed at stabilizing the region.

“For IOM, regional cooperation is essential to ensure safe, orderly, and regular migration and respond effectively to challenges,” said IOM Director General António Vitorino.

The new agreement provided an opportunity for tailored, joint approaches that address the complex drivers of conflict, instability, and forced displacement, he said, adding that “seeking such solutions will stand as a stepping stone in our overall collaborative frameworks toward improving conditions for populations in the Sahel.”

Meanwhile, UNISS continues working with all UN entities and partner nations on such efforts as the Generation Unlimited Sahel and helping Sahelians support their families, said Mr. Dieye, emphasizing that the current situation remains “extremely worrisome”.

“It will require a collective response,” he said. “No one country can deal with it alone. I think this has to land on the lap of the international community. After all, it is an international crime.”

What’s the difference between migrant smuggling and human trafficking?

Migrant smuggling and human trafficking are two distinct but often interconnected crimes, according to UNODC.

- While human trafficking aims to exploit a person, who may or may not be a migrant, the purpose of smuggling is, by definition, to make profits from facilitating illegal border crossing.

- Human trafficking can take place within the victim’s home country or in another country.

- Migrant smuggling always happens across national borders.

- Some migrants might start their journey by agreeing to be smuggled into a country illegally, but end up as victims of human trafficking when they are deceived, coerced or forced into an exploitative situation later in the process, for example being forced to work for no or very little money to pay for their transportation.

- Criminals may both smuggle and traffic people, employing the same routes and methods of transporting them.

- Smuggled migrants have no guarantee that those who smuggle them are not in fact human traffickers.

- Learn more about how UNODC is working to stamp out migrant smuggling and human trafficking.

© UN News (2023) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: UN News

Global Issues

Global Issues