Climate Justice and Equity

Author and Page information

This print version has been auto-generated from https://www.globalissues.org/article/231/climate-justice-and-equity

For a number of years, there have been concerns that climate change negotiations will essentially ignore a key principle of climate change negotiation frameworks: the common but differentiated responsibilities. This recognizes that historically:

- Industrialized nations have emitted far more greenhouse gas emissions than developing nations (even if some developing nations are only now increasing theirs) enabling a cheaper path to industrialization;

- Rich countries therefore face the biggest responsibility and burden for action to address climate change; and

- Rich countries therefore must support developing nations adapt to avoid the polluting (i.e. easier and cheaper) path to development—through financing and technology transfer, for example.

This notion of climate justice

is typically ignored by many rich nations and their mainstream media, making it easy to blame China, India and other developing countries, or gain credence in the false balancing

argument that if they must be subject to emission reductions then so must China and India. There may be a case for emerging nations to be subject to some reduction targets, but the burden of reductions must lie with industrialized countries.

In the meanwhile, rich nations have done very little within the Kyoto protocol to reduce emissions by any meaningful amount, while they are all for negotiating a follow on treaty that brings more pressure to developing countries to agree to emissions targets.

In effect, the more they delay the more the poor nations will have to save the Earth with their sacrifices (and if it works, as history shows, the rich and powerful will find a way to rewrite history to claim they were the ones that saved the planet).

On this page:

Why Don’t Poor Countries Have Emission Reduction Targets?

Global warming is primarily a result of the industrialization and motorization levels in the OECD countries, on whom the main onus for mitigation presently lies.

It has long been accepted that those industrialized nations that have been industrializing since the Industrial Revolution bear more responsibility for human-induced climate change. This is because greenhouse gases can remain in the atmosphere for decades.

With a bit of historical context then, claims of equity and fairness take on a different meaning than simply suggesting all countries should be reducing emissions by the same amount. But some industrialized nations appear to reject or ignore this premise.

Common goal but different responsibilities

During various stages of climate negotiations, the US complained about the apparent unfairness in the Kyoto Protocol2, which doesn’t commit developing nations to the same levels of reductions in global warming pollutants.

However, what Washington has not mention is that the developing nations are NOT the ones who have caused the pollution for the past 150 or so years and that it would be unfair to ask them to cut back at for the mistakes of the currently industrialized nations.

When the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was formulated and then signed and ratified in 1992 by most of the world’s countries (including the United States and other nations who would later back out of the subsequent Kyoto protocol), the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities was acknowledged. In short, this principle recognized that

- The largest share of historical and current global emissions of greenhouse gases has originated in developed countries;

- Per capita emissions in developing countries are still relatively low;

- The share of global emissions originating in developing countries will grow to meet their social and development needs.

That is,

- Today’s rich nations are responsible for global warming;

- It is unfair to expect the third world to make emissions reductions in the same way.

In addition, developing countries will also be tackling climate change in other ways. These three are discussed further:

Today’s Rich nations are responsible for global warming

Greenhouse gases tend to remain in the atmosphere for many decades so historical emissions are an important consideration.

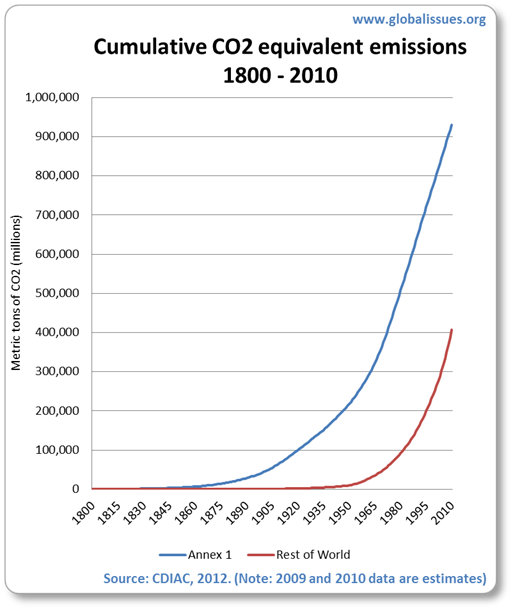

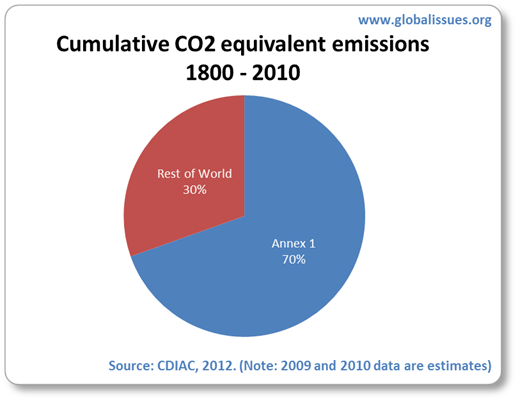

The following shows that the rich nations (known as Annex I countries

in UN climate change speak) have historically emitted more than the rest of the world combined, even though China, India and others have been growing recently. This is why the common but differentiated responsibilities

principle was recognized.

Historically, the rich countries have counted for around 70% of carbon emissions (even though they have represented only 20% of the world’s population, approximately):

The United Kingdom (the first empire to industrialize with heavy fossil fuel usage) as well as other European nations have emitted large amounts since their early path to development. Although it became an empire later than most European powers, the sheer size of the United States and its global dominance after World War II made it quickly overtake UK’s total emissions.

By contrast, the late entry to industrialization for China, India and other developing countries means their cumulative emissions have been far smaller.

Even though more recent media coverage and international meetings concentrate on getting India, China and other developing nations to reduce their emissions before rich countries do more, historical emissions show that the burden should really be on the rich countries:

No doubt, developing nations should be aware of their recent rise and also do more to curb their emissions. But given their later entry to industrialization and that their per capita emissions are even less than rich nations, more emission reduction could also be achieved per person in rich nations.

Greenhouse gases stay in the atmosphere for decades. It is rarely mentioned in Western mainstream media, but has been known for a while, as the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) noted back in 2002:

Industrialized countries set out on the path of development much earlier than developing countries, and have been emitting GHGs [Greenhouse gases] in the atmosphere for years without any restrictions. Since GHG emissions accumulate in the atmosphere for decades and centuries, the industrialized countries’ emissions are still present in the earth’s atmosphere. Therefore, the North is responsible for the problem of global warming given their huge historical emissions. It owes its current prosperity to decades of overuse of the common atmospheric space and its limited capacity to absorb GHGs.

And of course, this was enshrined in the common but differentiated responsibilities

principle a decade before that.

It is unfair to expect the third world to make emissions reductions to the same level as rich nations

It is therefore unfair to expect the third world to make emissions reductions, especially considering that their development and consumption is (more generally) for basic needs, while for the rich, it has moved on to luxury consumption and associated life styles.

According to a Christian Aid report (September 1999), industrialized nations should be owing over 600 billion dollars to the developing nations for the associated costs of climate changes15. This is three times as much as the conventional debt that developing countries owe the developed ones.

As the above-mentioned WRI report also adds: Much of the growth in emissions in developing countries results from the provision of basic human needs for growing populations, while emissions in industrialized countries contribute to growth in a standard of living that is already far above that of the average person worldwide. This is exemplified by the large contrasts in per capita carbons emissions between industrialized and developing countries. Per capita emissions of carbon in the U.S. are over 20 times higher than India, 12 times higher than Brazil and seven times higher than China.

As the above-mentioned CSE also adds:

Developing countries, on the other hand, have taken the road to growth and development very recently. In countries like India, emissions have started growing but their per capita emissions are still significantly lower than that of industrialized countries. The difference in emissions between industrialized and developing countries is even starker when per capita emissions are taken into account. In 1996, for instance, the emission of 1 US citizen equaled that of 19 Indians.

CSE is also worth quoting here at length from an article in mid-December 2007:

Responsibility needs rights.

The tragedy of the atmospheric common has been the lack of rights to this global ecological space. As a result, countries have borrowed or drawn heavily and without control. They have emitted greenhouse gases far in excess of what the Earth can withstand. This was because they could emit without limits or quotas and were “free riding” on this natural capital. Some researchers have called this the “natural debt” of the North, as against the financial debt of the South.

This is the science and the politics of CO2. One tonne of CO2 emitted in 1850 is the same as a tonne emitted today. The greenhouse gases … have long lifetime in the atmosphere; these gases are still warming the atmosphere, at any given year. The ‘sinks’—forests, oceans and soils—are the only cleaners of this dirt. The net emissions add up to the space that a nation has appropriated in the global atmospheric common and therefore its responsibility for the climate change.

Calculated in terms of the total emissions of each country, since the early 1900s, we find that every living American carries a natural debt burden of more than 1,050 tonnes of C02 (see graph: Cumulative CO2 emissions17). In comparison, every living Chinese has a natural debt of 68 tonnes and every living Indian, a mere 25 tonnes. Therefore, even with all the talks of India and China catching up with rich world in terms of total emissions, the fact is in terms of natural debt it will take many more decades before this happens.

This principle was accepted by the climate convention, which agreed that the rich world had to reduce its emissions to make space for the poor to grow. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol set the first, hesitant and weak, target for reduction by the rich countries. But this agreement has been more of less reneged on. The per capita emission of CO2 from fuel combustion in the US is still roughly 20 tonnes per year; between 6 tonnes and 12 tonnes for most European countries. This is not comparable to the per capita emissions of China, roughly 4 tonnes and 1.1 tonnes in India.

The above article also notes the disparities within nations, including countries such as India, where the wealthy do consume far more than the rich, and that needs addressing too.

(The slight difference in emissions capita quoted by the sources above are due to the differences in the date of the data and the changes that had taken place between.)

Furthermore, many emissions in countries such as India and China are from rich country corporations out-sourcing production to these countries. Products are then exported or sold to the rich. Yet, currently, the blame

for such emissions are put on the producer not the consumer. It is not a clear-cut issue though, as some producers create products and try to market them to consumers to buy, while other times, there is a market/consumer demand for certain products. Companies who can try to avoid more regulation and higher wages in richer countries may attempt to off-shore such production. As discussed on this site’s consumption19 section, some 80% of the world’s resources are consumed by the wealthiest 20% of the world (the rich countries). This portion has been higher in the past, suggesting that those countries should therefore bear the brunt of the targets. This issue is discussed in more detail in various part of this site’s trade and economic issues20 section.

Developing countries will also be tackling climate change in other ways

Under the Convention, the rich were to help provide means for the developing world to transition to cleaner technologies while developing:

The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments under the Convention will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments under the Convention related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.

Furthermore, many developing nations are already providing voluntary cuts and as they become larger polluters, they too will be subject to reduction mechanisms.

New Scientist reports that Brazil, China, India and Mexico and other such fast developing countries have slowed their rising greenhouse gas emissions by more than the total cuts demanded of rich nations by the Kyoto Protocol22 yet this is rarely reported by the mainstream when Bush and others point to China and India concerns.

Policies primarily intended to curb the air pollution from factories and cars or to save energy have had the side-effect of fighting global warming. Note, however, the emissions are still rising, but at a much slower rate.

At the end of 2005, Reuters reports that a Chinese state-owned energy firm plans to invest at least $2.48 billion over the next five years in biomass, garbage treatment and other alternative energy projects.

This company, China Energy Conservation Investment Corp., announced this in response to a new law in China promoting renewable energy23, which sets tariffs in favor of non-fossil energy such as wind, water and solar power and is due to take effect in January.

China has a goal of getting 15% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020, though the same report admits that China still largely depends on coal for its electricity (some 70%) and will continue to do so.

Compare that, however, to say the an industrialized country that feels it is taking a lead in climate change affairs: United Kingdom’s goal is for 10% of all its electricity to be from renewable sources24.

At the end of 2009, Reuters also reported on a new Chinese law requiring power grid operators to buy all the electricity that is produced by renewable energy generators 25, increasing the proportion of energy that comes from renewable sources, with harsh fines for failure to comply.

US News & World Report adds that China’s renewable energy market is expected to grow to $100 billion over the next 15 years27.

A 2002 report from the Pew Center for example, highlights how key developing nations have been able to significantly reduce their combined greenhouse gas emissions 28 by some 19 percent, or 300 million tons a year, with possibly another 300 million tons by 2010. Those nations are Brazil, China, India, Mexico, South Africa, and Turkey.

Various efforts reported by Pew included:

- Market and energy reforms to promote economic growth;

- Development of alternative fuels to reduce energy imports;

- Aggressive energy efficiency programs;

- Use of solar and other renewable energy to raise living standards in rural locations;

- Reducing deforestation;

- Slowing population growth; and

- Switching from coal to natural gas to diversify energy sources and reduce air pollution.

This shows that the rich nations can and should be able to do so as well.

An earlier report in 2000 from the WRI also notes that developing countries are already taking action to limit emissions29 (emphasis original).

In a report, earlier still (1999), WRI also noted that:

- Growth caps for the poor amount to guessing on a country’s future economic performance30;

- Modeling developing country climate change commitments after industrialized country commitments is not the way to go31, and could threaten the environmental integrity of the Kyoto Protocol, given the uncertainty of future emission levels and the international emissions trading provisions in the Protocol.

- For poorer countries, an alternative policy may therefore be appropriate (and WRI goes on to suggest one).

And as the following video from video journalist site, VJMovement, suggests, China is quite aware of the impacts climate change may have on its own people:

The political problem is that rich countries are demanding developing countries to cut emissions before they have really done so, or properly committed to assistance such as technology transfer and adaptation funds. In addition, the current global financial crisis33 makes finding those funds potentially more difficult.

What might a fair share of emissions look like?

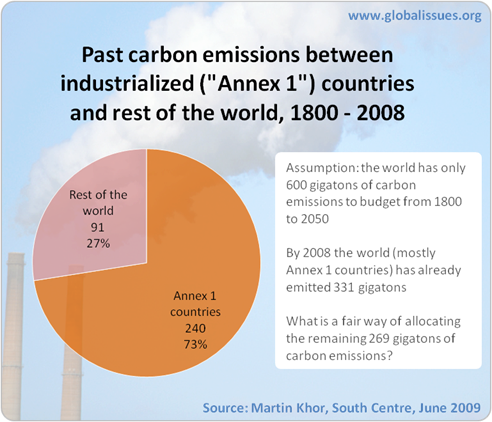

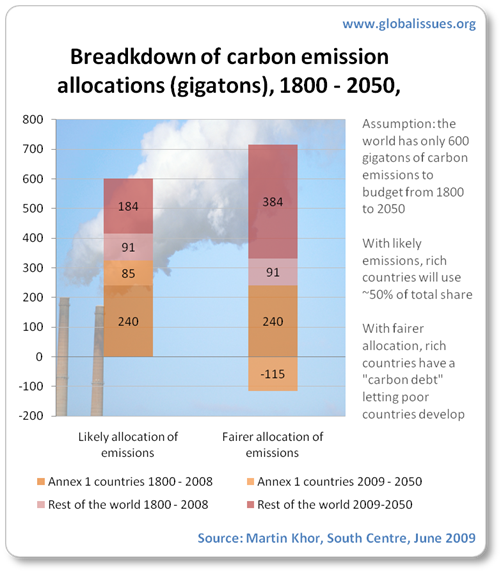

Martin Khor notes the historically large amount of emissions from rich nations that have helped them develop.

Assuming by 2050 that 600 gigatons of carbon emissions is the limit that needs to be reached to prevent climate change getting worse, Khor looked at fairer allocation of emissions based on per capita emissions, taking into account what has already been emitted by rich countries (Annex 1

) and non-Annex 1 countries (i.e the rest of the world).

Noting that rich countries have already had their chance to develop and emitted more in than their fair share in the process, is there a way to redress so the end result is equitable for all?

A fairer allocation is possible while allowing poorer countries to develop but would require the rich countries to cut back significantly.

This can be seen in the following:

By 2008, the rich nations had already counted for the majority of carbon emissions, since 1800: 240 gigatons (Gt), vs 91 Gt from the rest of the world:

But it is likely that emissions by 2050 will mean rich countries have ended up using some 325 Gt (of the 600 total that is aimed for), or just over 50%. Yet, it needs to be around 20% (because the rich nations are roughly 20% of the population):

The 20% allocation could be achieved if rich countries accept they owe a carbon debt

which would also allow the rest of the world to develop:

Khor describes the notion of negative emissions

which includes knowledge and technology sharing with developing nations to help them combat climate change.

It now seems unfair on rich countries! They now have to cut their emissions significantly and help finance poor countries’ to emit more! But there is a logic to this:

- The

polluting

ways the industrialized nations used to industrialize is not to be encouraged for the rest of the world. - Those polluting ways are also considered the cheaper, or easier way to develop, which, as the Centre for Science and Environment noted earlier, was akin to free-riding on the atmospheric commons.

- Given this

low-hanging

fruit is not encouraged for developing countries, their path to development requires more costly measures. - Given industrialized nations have used up most of the

low-hanging fruit

, it seems fair that they help developing countries down an alternative path (which would still lead to economic benefits for industrialized nations because they would likely be leaders in developing such technology required by developing nations).

In some ways, the above numbers are simplistic and generalized. For example

- Not all of today’s industrialized nations were necessarily industrialized in the past (though many were)

- Population ratios may have changed in this time period so such factors would need to be brought in to create more accurate numbers.

- Also, in the past industrialized nations have emitted greenhouse gases while producing items used by others around the world. (Although, industrialized nations have, for many years, consumed more resources compared to developing countries than they do today so have often produced for themselves more than for the poorer countries.)

- This producing for others also happens today. China for example, claims around one third of its production is for consumption by the rich part of the world, and there is more globalization today than in the past whereby poorer nations are encouraged to create exports for richer nations.

As crude and high-level as the actual numbers may be, it highlights that social justice and equity issues have been ignored from climate negotiations and from mainstream media discussions in the industrialized world, allowing views such as needing China and India to make drastic cuts more palatable than should be, perhaps.

The other challenge is that to achieve the reduction by 2050, reductions need to start in advance, while the developing nations are mostly poor, as Tom Athanasiou of EcoEquity36 highlights:

(Just as the above has been written, the global conservation organization, WWF, released a report detailing how carbon budgets can be allocated and shared equitably amongst nations 38 using principles similar to the above. They measure emissions using carbon dioxide equivalents (C02eq), rather than carbon which Khor uses above, but given the ratio of carbon in carbon dioxide is approximately 27%39, the 970gt CO2eq that WWF estimate as the budgetable global emissions between 1990 and 2050 is almost the same as Khor’s numbers.)

Climate negotiations ignoring social justice and equity

The above, and other principles in the Convention, formed what some described as the social justice and equity part of climate change issues. Unfortunately these have been largely ignored in the discussions which are usually dominated by the rich nations, and oil producing countries, who talk more about economic effectiveness only. In a way, this can be understood, because:

- Rich nations such as the United States, and OPEC countries, are worried about the economic impact of changing the fundamental underpinnings of their economies and their way of life.

- The social justice and equity dimension is a concern primarily for the third world. Without as strong a voice as the rich countries, when it comes to discussion and negotiation, this concern isn’t heard, understood, or seen as important.

Hence, when the US backed out of the Kyoto agreements on emission reductions citing, amongst other things, that China and India for example should also have emissions cuts imposed on them, these social justice and equity

dimensions were hardly considered, or treated as important enough. But considering the following:

- Meaningful assistance to other countries to transition to cleaner development has been lacking;

- Third world debt and poverty has diverted immense resources from sustainable development;

- Poor countries including China and India had already made reasonable emission cuts;

- Pressure from citizens in rich countries to clean up their environment has often actually led to moving those dirty industries/factories to the third world while still producing for the benefit or profit for the first world. This was eventually noted by the BBC, in December 2005, reporting on

new

research that shows similar fears40, despite these concerns being voiced many years ago.

These and many, many other related issues have hardly received detailed coverage either at all, or at least at the same time as the coverage of US reasons for backing out of Kyoto. Hence it is understandable why many US citizens would agree with the Bush Administration’s position on this, for example.

See this site’s section on climate change negotiations and actions41 and trade related issues42 for more on some of these aspects.

Rich Nations Have Outsourced

Their Carbon Emissions

Global trade is an important feature of the modern world. The production and global distribution of manufactured products thus form a large portion of global human carbon emissions.

The Kyoto Protocol assigns carbon emissions to countries based on where production takes place rather than where things are consumed.

For many years, critics of the Kyoto Protocol have long argued that this means rich countries, who have outsourced much of their manufacturing to developing nations have an accounting trick they can use to show more emissions reduction than developing nations. The above-mentioned BBC article noted back in 2005 that this outsourcing had taken place, but the idea of doing this came way before the Kyoto Protocol came into being.

In 1991 Larry Summers, then Chief Economist for the World Bank (and US Treasury Secretary, in the Clinton Administration, until George Bush and the Republican party came into power), had been a strong backer of structural adjustment policies43. He wrote in an internal memo:

Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of dirty industries to the LDCs [less developed countries]?… The economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable, and we should face up to that… Under-populated countries in Africa are vastly under-polluted; their air quality is probably vastly inefficiently low compared to Los Angeles or Mexico City… The concern over an agent that causes a one in a million change in the odds of prostate cancer is obviously going to be much higher in a country where people survive to get prostate cancer than in a country where under-five mortality is 200 per thousand.

Although the discussion above wasn’t about carbon emissions, the intention was the same: rather than directly address the problem, off-shoring dirty industries to the developing nations and let them deal with it.

More recently, The Guardian provided a useful summary of the impacts of this approach: carbon emissions cuts by developed countries since 1990 have been canceled out by increases in imported goods from developing countries44 — many times over.

They were summarizing global figures compiled and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US45. And the findings seemed to vindicate what many environmental groups had said for many years about the Kyoto Protocol as noted earlier.

In more detail:

According to standard data, developed countries can claim to have reduced their collective emissions by almost 2% between 1990 and 2008. But once the carbon cost of imports have been added to each country, and exports subtracted – the true change has been an increase of 7%. If Russia and Ukraine – which cut their CO2 emissions rapidly in the 1990s due to economic collapse – are excluded, the rise is 12%.

…

Much of the increase in emissions in the developed world is due to the US, which promised a 7% cut under Kyoto but then did not to ratify the protocol. Emissions within its borders increased by 17% between 1990 and 2008 – and by 25% when imports and exports are factored in.

In the same period, UK emissions fell by 28 million tonnes, but when imports and exports are taken into account, the domestic footprint has risen by more than 100 million tonnes. Europe achieved a 6% cut in CO2 emissions, but when outsourcing is considered that is reduced to 1%.

…

The study shows a very different picture for countries that export more carbon-intensive goods than they import. China, whose growth has been driven by export-based industries, is usually described as the world's largest emitter of CO2, but its footprint drops by almost a fifth when its imports and exports are taken into account, putting it firmly behind the US. China alone accounts for a massive 75% of the developed world's offshored emissions, according to the paper.

Politics and Interests

At the time of the end of the CoP-8 climate change conference, what appears to be a change in principle by the European Union, towards the position of the developing countries has emerged. That is, as Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) comments47, Denmark, currently president of the European Union, announced yesterday [October 31, 2002] that developing countries would not get any money for adapting to climate change until they start discussing reduction commitments.

Not only can this be described as blackmail, as CSE also highlight, but in addition, rich nations themselves have shied away from their commitments, amounting to hypocrisy.

As CSE continued, Adaptation funds have been on the negotiations agenda for several years now. Industrialized countries, including progressive countries like Denmark, have run away from committing anything concrete, and developing countries have not been able to pin down any liability on them.

(CSE has also been critical of leaders in developing countries who are equally to blame for encouraging the perception that they can be bought

appearing to respond to money only such, giving an opportunity for some rich nations to exploit that.)

Economics and political agendas always makes it difficult49 to produce a treaty that all nations can agree to easily. The wealthier and more powerful nations are naturally able to exert more political clout and influence. The US, for example, has pushed for different solutions that will allow it to maintain its dominance. An example of that is trading50 in emissions, which has seen a number of criticisms.

The way current climate change negotiations have been going unfortunately suggests the developed world will position themselves to use the land of the developing and poor nations to further their own emissions reduction, while leaving few such easy options for the South, as summarized by the following as well:

Investments in

carbon sinks(such as large-scale tree plantations) in the South would result in land being used at the expense of local people, accelerate deforestation, deplete water resources and increase poverty. Entitling the North to buy cheap emission credits from the South, through projects of an often exploitative nature, constitutescarbon colonialism. Industrialised countries and their corporations will harvest thelow-hanging fruit(the cheapest credits), saddling Southern countries with only expensive options for any future reduction commitments they might be required to make.

Savingthe Kyoto Protocol Means Ending the Market Mania51, Corporate Europe Observatory, July 2001

More Information

For more information on this, you can start at the following links:

- Equity Watch52 from Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment.

- Climate Justice53 section of a scathing report on business interests in climate negotiations from the Corporate Europe Observatory.

- Equity—Bottom line or wishful thinking? 54 from a report from PANOS on the Climate Change Convention.

- This web site’s section on the Kyoto conference55 that looks more at the issue of developing countries and the US position.

- Climate Justice56 from CorpWatch heavily criticizes corporate interests and influence in climate negotiations.

- Christian Aid goes as far as criticizing the Kyoto protocol as a fraud57 because of the unfairness by rich countries. As they point out:

- 4.5 per cent of the world’s population lives in the USA and emits 22 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gases.

- 17 per cent of the world’s population lives in India and emits 4.2 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gases.

- Britain emits 9.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide per person per year, while Honduras emits 0.7 tonnes per person.

- The world’s poorest countries account for just 0.4 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions. 45 per cent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions are produced by the G8 countries alone.

- EcoEquity58 provides a number of articles and commentary.

0 articles on “Climate Justice and Equity” and 2 related issues:

Climate Change and Global Warming

The climate is changing. The earth is warming up, and there is now overwhelming scientific consensus that it is happening, and human-induced. With global warming on the increase and species and their habitats on the decrease, chances for ecosystems to adapt naturally are diminishing. Many are agreed that climate change may be one of the greatest threats facing the planet. Recent years show increasing temperatures in various regions, and/or increasing extremities in weather patterns.

The climate is changing. The earth is warming up, and there is now overwhelming scientific consensus that it is happening, and human-induced. With global warming on the increase and species and their habitats on the decrease, chances for ecosystems to adapt naturally are diminishing. Many are agreed that climate change may be one of the greatest threats facing the planet. Recent years show increasing temperatures in various regions, and/or increasing extremities in weather patterns.

This section explores some of the effects of climate change. It also attempts to provide insights into what governments, companies, international institutions, and other organizations are attempting to do about this issue, as well as the challenges they face. Some of the major conferences in recent years are also discussed.

Read “Climate Change and Global Warming” to learn more.

Environmental Issues

Environmental issues are also a major global issue. Humans depend on a sustainable and healthy environment, and yet we have damaged the environment in numerous ways. This section introduces other issues including biodiversity, climate change, animal and nature conservation, population, genetically modified food, sustainable development, and more.

Environmental issues are also a major global issue. Humans depend on a sustainable and healthy environment, and yet we have damaged the environment in numerous ways. This section introduces other issues including biodiversity, climate change, animal and nature conservation, population, genetically modified food, sustainable development, and more.

Read “Environmental Issues” to learn more.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues