Foreign Aid for Development Assistance

Author and Page information

This print version has been auto-generated from https://www.globalissues.org/article/35/foreign-aid-development-assistance

Foreign aid or (development assistance) is often regarded as being too much, or wasted on corrupt recipient governments despite any good intentions from donor countries. In reality, both the quantity and quality of aid have been poor and donor nations have not been held to account.

There are numerous forms of aid, from humanitarian emergency assistance, to food aid, military assistance, etc. Development aid has long been recognized as crucial to help poor developing nations grow out of poverty.

In 1970, the world’s rich countries agreed to give 0.7% of their GNI (Gross National Income) as official international development aid, annually. Since that time, despite billions given each year, rich nations have rarely met their actual promised targets. For example, the US is often the largest donor in dollar terms, but ranks amongst the lowest in terms of meeting the stated 0.7% target.

Furthermore, aid has often come with a price of its own for the developing nations:

- Aid is often wasted on conditions that the recipient must use overpriced goods and services from donor countries

- Most aid does not actually go to the poorest who would need it the most

- Aid amounts are dwarfed by rich country protectionism that denies market access for poor country products, while rich nations use aid as a lever to open poor country markets to their products

- Large projects or massive grand strategies often fail to help the vulnerable as money can often be embezzled away.

This article explores who has benefited most from this aid, the recipients or the donors.

On this page:

- Governments Cutting Back on Promised Responsibilities

- Foreign Aid Numbers in Charts and Graphs

- Are numbers the only issue?

- Aid as a foreign policy tool to aid the donor not the recipient

- Aid Amounts Dwarfed by Effects of First World Subsidies, Third World Debt, Unequal Trade, etc

- But aid could be beneficial

- Trade and Aid

- Improving Economic Infrastructure

- Use aid to Empower, not to Prescribe

- Rich donor countries and aid bureaucracies are not accountable

- Democracy-building is fundamental, but harder in many developing countries

- Failed foreign aid and continued poverty: well-intentioned mistakes, calculated geopolitics, or a mix?

Governments Cutting Back on Promised Responsibilities

Trade, not aid

is regarded as an important part of development promoted by some nations. But in the context of international obligations, it is also criticized by many as an excuse for rich countries to cut back aid that has been agreed and promised at the United Nations.

Rich Nations Agreed at UN to 0.7% of GNP To Aid

Recently, there was an EU pledge to spend 0.56% of GNI on poverty reduction by 2010, and 0.7% by 2015.

However,

- The donor governments promised to spend 0.7% of GNP on ODA (Official Development Assistance) at the UN General Assembly in 1970—some 40 years ago

- The deadline for reaching that target was the mid-1970s.

- By 2015 (the year by when the Millennium Development Goals are hoped to be achieved) the target will be 45 years old.

This target was codified in a United Nations General Assembly Resolution, and a key paragraph says:

In recognition of the special importance of the role which can be fulfilled only by official development assistance, a major part of financial resource transfers to the developing countries should be provided in the form of official development assistance. Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 per cent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the Decade.

What was to be the form of aid?

Financial aid will, in principle, be untied. While it may not be possible to untie assistance in all cases, developed countries will rapidly and progressively take what measures they can … to reduce the extent of tying of assistance and to mitigate any harmful effects [and make loans tied to particular sources] available for utilization by the recipient countries for the purpose of buying goods and services from other developing countries.

… Financial and technical assistance should be aimed exclusively at promoting the economic and social progress of developing countries and should not in any way be used by the developed countries to the detriment of the national sovereignty of recipient countries.

Developed countries will provide, to the greatest extent possible, an increased flow of aid on a long-term and continuing basis.

The aid is to come from the roughly 22 members of the OECD, known as the Development Assistance Committee (DAC). [Note that terminology is changing3. GNP, which the OECD used up to 2000 is now replaced with the similar GNI, Gross National Income which includes a terms of trade adjustment. Some quoted articles and older parts of this site may still use GNP or GDP.]

ODA is basically aid from the governments of the wealthy nations, but doesn’t include private contributions or private capital flows and investments. The main objective of ODA is to promote development. It is therefore a kind of measure on the priorities that governments themselves put on such matters. (Whether that necessarily reflects their citizen’s wishes and priorities is a different matter!)

Almost all rich nations fail this obligation

Even though these targets and agendas have been set, year after year almost all rich nations have constantly failed to reach their agreed obligations of the 0.7% target. Instead of 0.7%, the amount of aid has been around 0.2 to 0.4%, some $150 billion short each year.

Furthermore, the quality of the aid has been poor. As Pekka Hirvonen from the Global Policy Forum summarizes:

Recent increases [in foreign aid] do not tell the whole truth about rich countries’ generosity, or the lack of it. Measured as a proportion of gross national income (GNI), aid lags far behind the 0.7 percent target the United Nations set 35 years ago. Moreover, development assistance is often of dubious quality. In many cases,

- Aid is primarily designed to serve the strategic and economic interests of the donor countries;

- Or [aid is primarily designed] to benefit powerful domestic interest groups;

- Aid systems based on the interests of donors instead of the needs of recipients’ make development assistance inefficient;

- Too little aid reaches countries that most desperately need it; and,

- All too often, aid is wasted on overpriced goods and services from donor countries.

The Cold War years saw a high amount of aid (though not near the 0.7% mark) as each super power and their allies aided regimes friendly to their interests. The end of the Cold War did not see some of the savings from the reduced military budgets being put towards increased aid, as hoped. Instead, as noted by the development organization, the South Centre, developing countries found themselves competing with a number of countries in transition for scarce official assistance5.

As others have long criticized, aid had a geopolitical value for the donor countries as aid increased when a Cold War had to be fought. (A long decline in the post Cold War 1990s has seen another rise, this time to fight terrorism, also detailed below.)

The issues raised by Hirvonen above are detailed further below. But before going into the poor quality of aid, a deeper look at the numbers:

Some donate many dollars, but are low on GNI percent

Some interesting observations can be made about the amount of aid. For example:

- USA’s aid, in terms of percentage of their GNP has almost always been lower than any other industrialized nation in the world, though paradoxically since 2000, their dollar amount has been the highest.

- Between 1992 and 2000, Japan had been the largest donor of aid, in terms of raw dollars. From 2001 the United States claimed that position, a year that also saw Japan’s amount of aid drop by nearly 4 billion dollars.

Aid increasing since 2001 but still way below obligations

Throughout the 1990s, ODA declined from a high

of 0.33% of total DAC aid in 1990 to a low of 0.22% in 1997. 2001 onwards has seen a trend of increased aid. Side NoteThe UN noted the irony that

the decline in aid came at a time where conditions were improving for its greater effectiveness

6. According to the World Bank, overall, the official development assistance worldwide had been decreasing about 20% since 19907.

Between 2001 and 2004, there was a continual increase in aid, but much of it due to geo-strategic concerns of the donor, such as fighting terrorism. Increases in 2005 were largely due to enormous debt relief for Iraq, Nigeria, plus some other one-off large items.

(As will be detailed further below, aid has typically followed donor’s interests, not necessarily the recipients, and as such the poorest have not always been the focus for such aid. Furthermore, the numbers, as low as they are, are actually more flattering to donor nations than they should be: the original definition of aid was never supposed to include debt relief or humanitarian emergency assistance, but instead was meant for development purposes. This is discussed further below, too.)

In 2009, the OCED and many others feared official aid would decline due to the global financial crisis22. They urged donor nations to make aid countercyclical

; not to reduce it when it is needed most — by those who did not cause the crisis.

And indeed, for 2009, aid did increase23 as official stats from the OECD shows. It rose 0.7% from just under $123 bn in 2008 to just over $123 bn in 2009 (at constant 2008 prices).

In 2011, the OECD noted a 6.5% increase in official development aid in 2010 over the previous year24 to $129 billion, but it still averaged only 0.32% of the combined GNI of donor countries — less than half of what had been promised long ago. But they also warned about worrying trends for the future; donor countries are expecting to reduce the rate of increased official aid.

The OECD also noted that due to continued failure to meet pledged aid in recent years (some nations have met those pledges, however), a code of good pledging practice was to be drawn up, which might be a first step towards better donor accountability.

2011: first aid decline in years

In 2012, the OECD noted an almost 3% decline in aid over 2010’s aid25 — the first decline in a while. Although this decline was expected at some point because of the financial problems in most wealthy nations, those same problems are rippling to the poorest nations, so a drop in aid (ignoring unhealthy reliance on it for the moment) is significant for them. It would also not be surprising if aid declines or stays stagnant for a while, as things like global financial problems not only take a while to ripple through, but of course take a while to overcome.

During recent years, some developing countries have been advancing (think China, India, Brazil, etc). So if there was declining aid due to many no longer needing it then that would be understandable. However, as the data shows, whether it has been recent years, or throughout the history of DAC aid, the poorest countries have received only a quarter of all aid. Even during recent increases in aid, these allocations did not change. In addition, as industrialized nations’ attention will turn towards their own economies, aid will be less of an issue, and as economics editor of the Guardian notes,

The fizz has gone out of the anti-poverty campaign groups. … their own performance … in recent years has been distinctly lacklustre. Even in the good years, politicians had to be pushed into action, and this was nearly always the result of public demands for change orchestrated by development groups. Until the spirit and the energy that led to Jubilee 2000 and Make Poverty History is rekindled, western politicians will be able to get away with breaking their promises.

(The first comment in the above article also makes a point that despite the predictable aid fall, it is to the industrialized nations’ credit that it didn’t fall by a much larger amount given the situation most of them are in, economically.)

2013: aid rebounds

In 2014, the OCED noted that Development aid rose by 6.1% in real terms in 2013 to reach the highest level ever recorded27, despite continued pressure on budgets in OECD countries since the global economic crisis. This rise was a rebound after two years of falling volumes, as a number of governments stepped up their spending on foreign aid.

However, it was also noted that assistance to the neediest countries continued to fall, which raises worries about the purpose of the increased aid. As the rest of this article has shown, for decades, much foreign aid has been less about helping the recipient, but furthering agendas of donor countries, for example to gain favorable access to resources or markets in recipient countries. It may be too early to tell for sure, but in the context of the financial crisis that has hurt donor countries particularly, some of the increase in aid may be to help with domestic economic concerns.

While the financial crisis does show the reliance on aid is not a good strategy for poor countries at any time, some have little choice in the short term.

Foreign Aid Numbers in Charts and Graphs

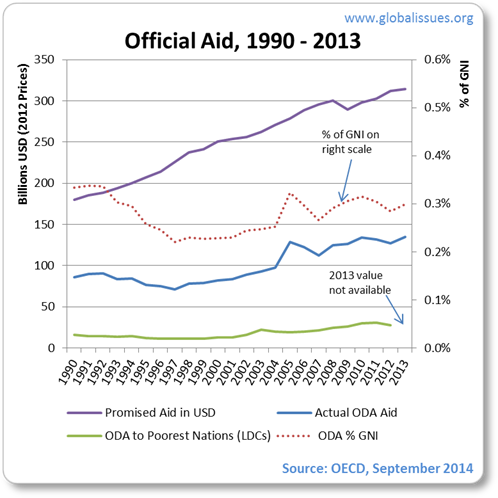

As the following chart shows

- Donor nations’ wealth (GNI) generally increased through the 1990s to 2010

- The levels of aid (tied to that growth) should have increased too

- Instead, in the 1990s it actually fell, while picking up in the 2000s. (Some of those recent rises, especially the large increases, were almost entirely due to debt write-off for a handful of countries — such as Iraq.)

- Aid for the poorest countries remained at a steady dollar amount in this period.

- Given overall wealth of donors had increased, this in effect meant that they reduced their aid to the poorest countries.

- Despite the loss in GNI in 2009 due to the financial crisis, aid did increase slightly.

It should be noted that in 2009 when donor nations had lower GNI due to the global financial crisis they still increased their aid in % terms, perhaps heeding the OECD’s plea mentioned earlier. The expected decline in aid eventually occurred in 2011, as effects from the global financial crisis take time to ripple through in terms of policy impacts. But the decline was perhaps not as sharp as could have been expected.

The charts and data below are reproduced from the OECD (using their latest data, at time of writing. It will be updated when new data becomes available).

Net ODA 2013

Details: % of GNI

| Country | Aid amount by GNI |

|---|---|

Source: OECD Development Statistics Online29 last accessed Saturday, April 07, 2012 If you are viewing this table on another site, please see http://www.globalissues.org for further details. | |

| Norway | |

| Sweden | |

| Luxembourg | |

| Denmark | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Netherlands | |

| Finland | |

| Switzerland | |

| Belgium | |

| Ireland | |

| France | |

| Germany | |

| Australia | |

| Austria | |

| Canada | |

| Iceland | |

| New Zealand | |

| Japan | |

| Portugal | |

| United States | |

| Italy | |

| Spain | |

| Greece | |

| Korea | |

| Slovenia | |

| Czech Republic | |

| Poland | |

| Slovak Republic | |

Details: Aid in $

| Country | Aid amount by dollars |

|---|---|

Source: OECD Development Statistics Online30 last accessed Saturday, April 07, 2012 If you are viewing this table on another site, please see http://www.globalissues.org for further details. | |

| United States | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Japan | |

| Germany | |

| France | |

| Sweden | |

| Norway | |

| Netherlands | |

| Australia | |

| Canada | |

| Switzerland | |

| Italy | |

| Denmark | |

| Belgium | |

| Spain | |

| Korea | |

| Finland | |

| Austria | |

| Ireland | |

| Portugal | |

| Poland | |

| New Zealand | |

| Luxembourg | |

| Greece | |

| Czech Republic | |

| Slovak Republic | |

| Slovenia | |

| Iceland | |

Raw data

| ODA in U.S. Dollars (Millions) | ODA as % of GNI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

Source: OECD Development Statistics Online31 last accessed Saturday, April 07, 2012 Note: The U.N. ODA agreed target is 0.7 percent of GNI. Most nations do not meet that target. | |||||||||

| 1. | Australia | 4,459 | 4,967 | 5,403 | 5,158 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| 2. | Austria | 1,218 | 1,046 | 1,106 | 1,113 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| 3. | Belgium | 3,033 | 2,646 | 2,315 | 2,174 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.45 |

| 4. | Canada | 5,643 | 5,494 | 5,650 | 5,007 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.27 |

| 5. | Czech Republic | 224 | 230 | 220 | 208 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| 6. | Denmark | 2,871 | 2,775 | 2,693 | 2,795 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| 7. | Finland | 1,368 | 1,337 | 1,320 | 1,367 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| 8. | France | 12,889 | 12,199 | 12,028 | 10,854 | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.41 |

| 9. | Germany | 12,944 | 13,219 | 12,939 | 13,328 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.38 |

| 10. | Greece | 494 | 390 | 327 | 302 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| 11. | Iceland | 30 | 24 | 26 | 33 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.26 |

| 12. | Ireland | 880 | 850 | 808 | 793 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.45 |

| 13. | Italy | 2,998 | 4,068 | 2,737 | 3,104 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| 14. | Japan | 11,827 | 10,723 | 10,605 | 14,486 | 0.2 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.23 |

| 15. | Korea | 1,235 | 1,315 | 1,597 | 1,674 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| 16. | Luxembourg | 419 | 390 | 399 | 403 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1 | 1 |

| 17. | Netherlands | 6,322 | 5,942 | 5,523 | 5,181 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.67 |

| 18. | New Zealand | 391 | 431 | 449 | 441 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.26 |

| 19. | Norway | 4,975 | 4,700 | 4,753 | 5,534 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| 20. | Poland | 370 | 390 | 421 | 457 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.1 |

| 21. | Portugal | 629 | 652 | 581 | 462 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.23 |

| 22. | Slovak Republic | 74 | 81 | 80 | 82 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| 23. | Slovenia | 58 | 58 | 58 | 59 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| 24. | Spain | 5,774 | 3,857 | 2,037 | 2,112 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| 25. | Sweden | 4,930 | 5,419 | 5,240 | 5,568 | 0.97 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| 26. | Switzerland | 2,570 | 2,890 | 3,056 | 3,161 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| 27. | United Kingdom | 13,931 | 13,901 | 13,891 | 17,755 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.72 |

| 28. | United States | 31,490 | 31,460 | 30,687 | 31,080 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

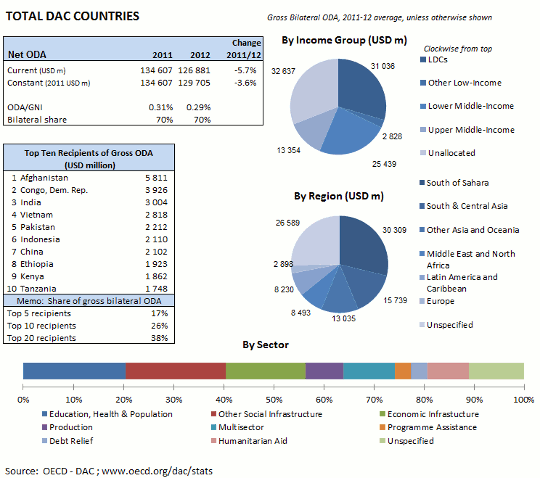

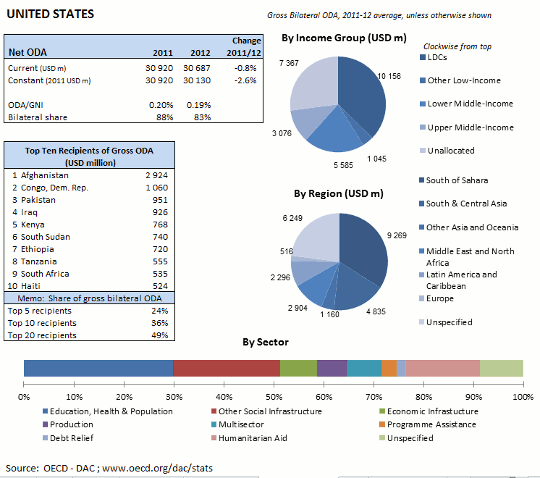

And who gets what?

The OECD web site also provides some breakdowns of how the money is given:

All DAC aid

From USA

Other countries

You can also see a full list of country breakdowns32 from the OECD web site.

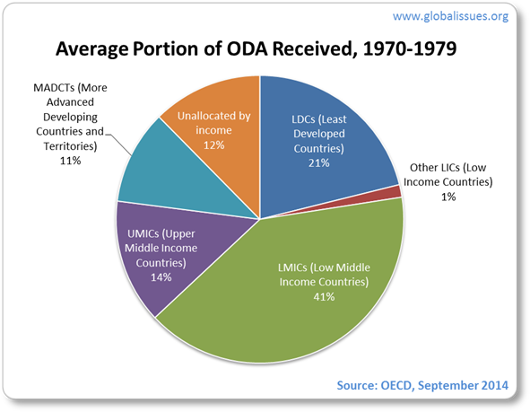

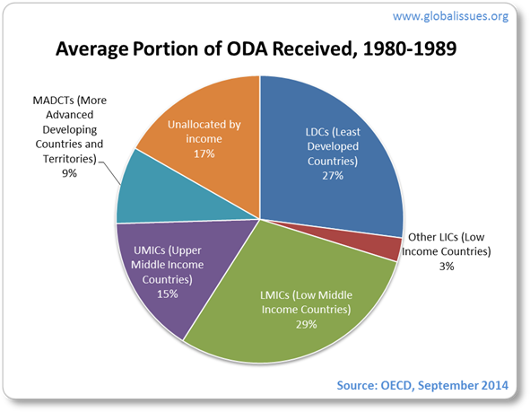

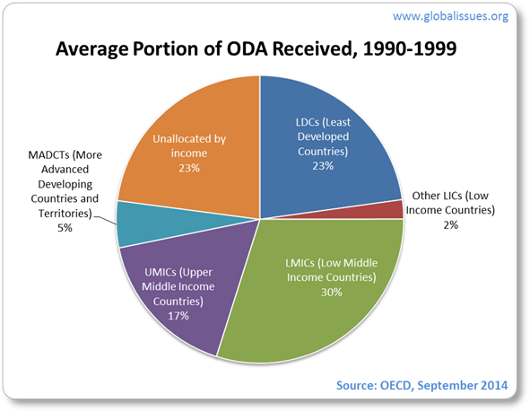

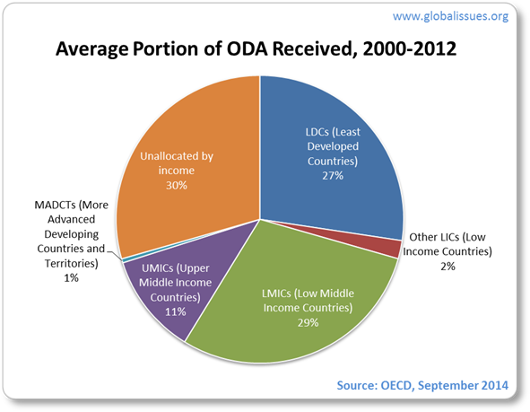

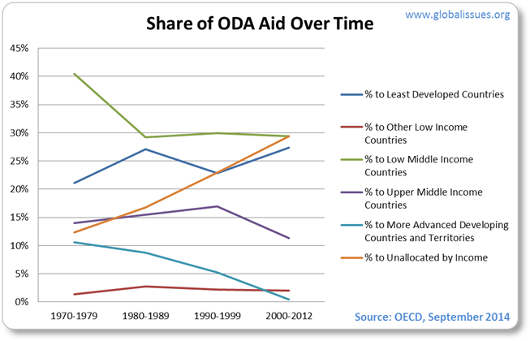

When broken down by region since 1970 the poorest countries have received just a quarter of all DAC aid:

Recent years, however, show a similar trend, with the poorest countries receiving a quarter of all aid:

While aid to the wealthier developing countries has reduced somewhat, the portion going to the poorest countries has hardly changed. In effect, most ODA aid does not appear to go to the poorest nations like we might naturally assume it would:

Aid money is actually way below what has been promised

2006 onwards is typically regarded as years of high aid volumes. However, at around 0.3% of GNI, if all DAC countries had given their full 0.7%, 2010’s aid alone would have been almost $284 billion (at 2010 prices), or an increase of almost $159 billion.

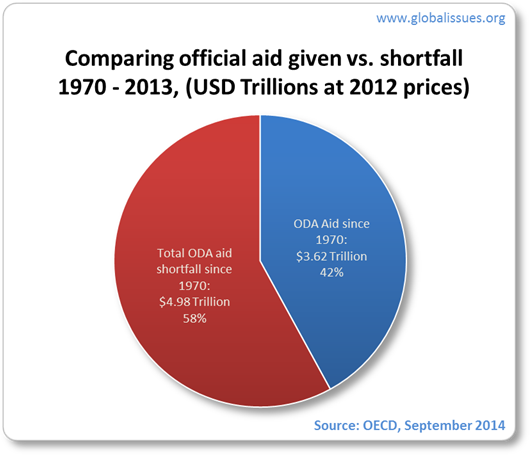

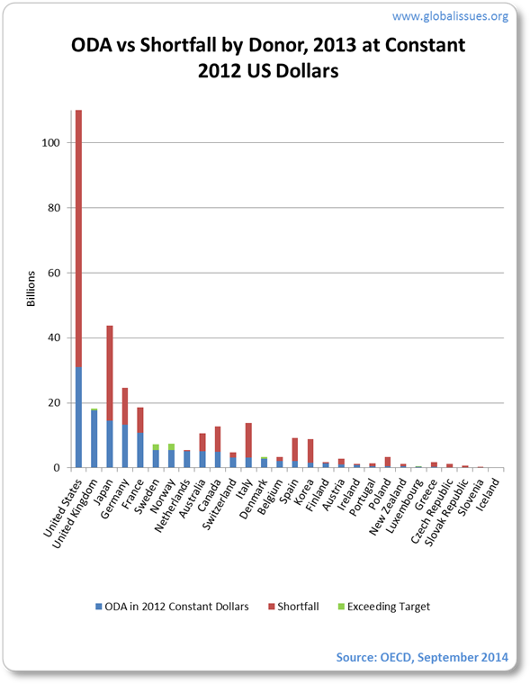

Considering the typical aid amount at around 0.25 to 0.4% of GNI for over 40 years, the total shortfall is a substantial and staggering amount: just under $5 trillion aid shortfall at 2012 prices:

The numbers are probably flattering donors too much, for (as detailed further below), a lot of development aid

today includes items not originally designated for this purpose (such as debt relief, emergency relief, etc.)

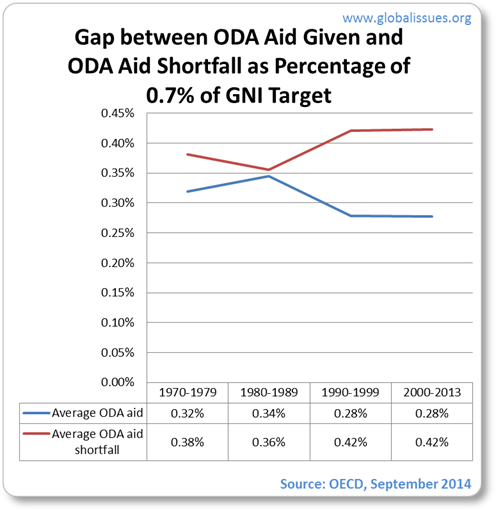

Averaging this data since 1970, when the target of donating 0.7% of national income was agreed, shows the following:

Between 1970 and 2013, the shortfall in aid has been 58%:

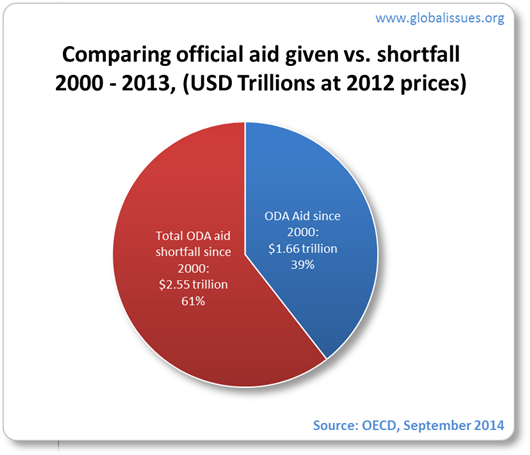

Taking data since 2000 up to 2013, the shortfall increases to 61%:

While dollar amounts of aid increases, the gap between the promised amount (0.7% of GNI) and the actual given seems to be increasing.

This gap was quite small during the 70s, and got smaller in the 80s, but has since widened considerably. (But even when the gap was close, the average ODA aid was around 0.35% of GNI at best, still far below the promised 0.7%.)

Taking just the latest figures (at time of writing), many nations, while seemingly providing large quantities of aid, are far below the levels they had agreed:

(See also the side note, Official global foreign aid shortfall: $5 trillion33 for more details.)

Side note on private contributions

As an aside, it should be emphasized that the above figures are comparing government spending. Such spending has been agreed at international level and is spread over a number of priorities.

Individual/private donations may be targeted in many ways. However, even though the charts above do show US aid to be poor (in percentage terms) compared to the rest, the generosity of the American people is far more impressive than their government. Private aid/donation typically through the charity of individual people and organizations can be weighted to certain interests and areas. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note for example, based on estimates in 2002, Americans privately gave at least $34 billion overseas — more than twice the US official foreign aid of $15 billion at that time:

- International giving by US foundations: $1.5 billion per year

- Charitable giving by US businesses: $2.8 billion annually

- American NGOs: $6.6 billion in grants, goods and volunteers.

- Religious overseas ministries: $3.4 billion, including health care, literacy training, relief and development.

- US colleges scholarships to foreign students: $1.3 billion

- Personal remittances from the US to developing countries: $18 billion in 2000

- Source: Dr. Carol Adelman, Aid and Comfort34, Tech Central Station, 21 August 2002.

Although Adelman admitted that there are no complete figures for international private giving

she still claimed that Americans are clearly the most generous on earth in public—but especially in private—giving

. While her assertions should be taken with caution, the numbers are high.

The Center for Global Prosperity, from the Hudson Institute, (whose director is Adelman) published its first Index of Global Philanthropy35 in 2006, which contained updated numbers from those stated above. The total of US private giving, since Adelman’s previous report, had increased to a massive $71 billion in 2004. Page 16 of their report breaks it down as follows:

- International giving by US foundations: $3.4 billion

- Charitable giving by US businesses: $4.9 billion

- American NGOs: $9.7

- Religious overseas ministries: $4.5

- US colleges scholarships to foreign students: $1.7 billion

- Personal remittances from the US to developing countries: $47 billion.

While the majority of the increase was personal remittances ($18 bn in 2000 to $47 bn in 2004), other areas have also seen increases.

Side Note on Private Remittances

Globally, private remittances have increased tremendously in recent years, especially as a number of developing countries have seen rapid growth and economic migration has increased amongst these nations.

In 2005, private remittances were estimated to be around $167 billion36, far more than total government aid.

In 2008, the World Bank estimated private remittances between 350 to 650 billion dollars were sent back home by 150 million international migrants37.

Many economists and others, including Adelman in the article above, point out that personal remittances are effective. They don’t require the expensive overhead of government consultants, or the interference of corrupt foreign officials. Studies have shown that roads, clinics, schools and water pumps are being funded by these private dollars. For most developing countries, private philanthropy and investment flows are much larger than official aid.

Unfortunately Adelman doesn’t cite the studies she mentions because these private dollars

do not seem to be remittance dollars, but private investment. Economists at the IMF surveyed literature on remittances and admitted that, the role of remittances in development and economic growth is not well understood … partly because the literatures on the causes and effects of remittances remain separate.

When they tried to see what role remittances played, they concluded that

remittances have a negative effect on economic growth

38

as it usually goes into private consumption, and takes place under asymmetric information and economic uncertainty.

Even if that turns out to be wrong, the other issue also is whether personal remittances can be counted as American giving, as people point out that it is often foreign immigrant workers sending savings back to their families in other countries. Political commentator Daniel Drezner takes up this issue39 arguing, Americans aren’t remitting this money—foreign nationals are.

Comparing Adelman’s figures with her previous employer’s, USAID, Drezner adds that Adelman’s figure is accurate if you include foreign remittances.

However, if you do not count foreign remittances then it matches the numbers that the research institute, the Center for Global Development uses in their rankings (see below).

Finally, Drezner suggests that Adelman is not necessarily incorrect in her core thesis that Americans are generous, but lumping remittances in with charity flows exaggerates the generosity of Americans as a people.

UNICEF also notes the dangers of counting on personal remittances solely based on economic value40, as reported by Inter Press Service. Latin America alone received some $45 billion in remittances in 2004, almost 27% of the total. At a regional conference, noting a Mexican household survery showing remittances contributed to improved provision of child care, the United Nations children’s charity, UNICEF, warned that the importance of family unity cannot be underestimated in terms of child well-being. If a parent is away working in another country, for a child, the loss of their most important role models, nurturers and caregivers, … has a significant psychosocial impact that can translate into feelings of abandonment, vulnerability, and loss of self-esteem, among others.

In addition, as the global financial crisis41 starts to spread, private remittances will decrease42, as well as foreign aid in general. Some nations rely a lot on these remittances. Remittances to Sri Lanka, for example, make up some 70% of the country’s trade deficit, according to the Inter Press Service (see previous link). This raises questions as to whether aid and remittances are sustainable in the long term or signal a more fundamental economic problem, as discussed further below.

Adjusting Aid Numbers to Factor Private Contributions, and more

David Roodman, from the CGD, attempts to adjust the aid numbers by including subjective factors43:

- Quality of recipient governance as well as poverty;

- Penalizing tying of aid;

- Handling reverse flows (debt service) in a consistent way;

- Penalizes project proliferation (overloading recipient governments with the administrative burden of many small aid projects);

- and rewards tax policies that encourage private charitable giving to developing countries.

In doing so, the results (using 2002 data, which was latest available at that time) produced:

| Country | Quality-adjusted aid as percent of GDP |

|---|---|

Source: David Roodman, An Index of Donor Performance44, Center for Global Development, April 2004 If you are viewing this table on another site, please see https://www.globalissues.org45 for further details. | |

| Sweden | |

| Denmark | |

| Netherlands | |

| Norway | |

| France | |

| Belgium | |

| Switzerland | |

| Finland | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Austria | |

| Germany | |

| Canada | |

| Ireland | |

| Australia | |

| Italy | |

| Portugal | |

| Japan | |

| Greece | |

| Spain | |

| United States | |

| New Zealand | |

You can also view this chart as an image46.

Interesting observations included:

- Contrary to popular belief, the US is not the only nation with tax incentives to encourage private contributions. (Only Austria, Finland and Sweden do not offer incentives.)

- Factoring that in, the US ranks joint 19th out of 21

- Japan fairs a lot worse

Roodman also admits that many—perhaps most—important aspects of aid quality are still not reflected in the index—factors such as the realism of project designs and the effectiveness of structural adjustment conditionality.

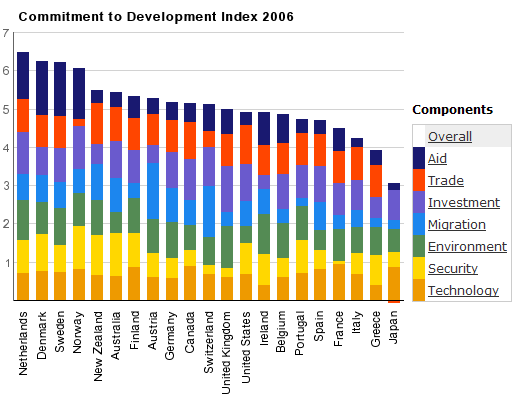

Ranking the Rich based on Commitment to Development

The CGD therefore attempts to factor in some quality measures based on their commitment to development47 for the world’s poor. This index considers aid, trade, investment, migration, environment, security, and technology.

Their result shows the Netherlands first, Japan last, and the US ranking thirteenth, just behind the United Kingdom, out of 21 total. As David Roodman notes in his announcement of the 2006 Commitment to Development Index48, As in the past, the G-7

leading industrial nations

have not led on the [Commitment to Development Index]; Germany, top among them, is in 9th place overall.

Recent claims of some leading industrial nations

being stingy

may put people on the defensive, but many nations whom we are told are amongst the world’s best, can in fact, do better. The results were charted as follows:

Adelman, further above noted that the US is clearly the most generous on earth in public—but especially in private—giving

, yet the CGD suggests otherwise, saying that the US does not close the gap with most other rich countries

49; The US gives 13c/day/person in government aid….American’s private giving—another 5c/day—is high by international standards but does not close the gap with most other rich countries. Norway gives $1.02/day in public aid and 24c/day in private aid

per person. (These numbers will change of course, year by year, but the point here is that Adelman’s assertion—one that many seem to have—is not quite right.)

Private donations and philanthropy

Government aid, while fraught with problems (discussed below), reflects foreign policy objectives of the donor government in power, which can differ from the generosity of the people of that nation. It can also be less specialized than private contributions and targets are internationally agreed to be measurable.

Private donations, especially large philanthropic donations and business givings, can be subject to political/ideological or economic end-goals and/or subject to special interest. A vivid example of this is in health issues around the world50. Amazingly large donations by foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are impressive, but the underlying causes of the problems are not addressed, which require political solutions. As Rajshri Dasgupta comments:

Private charity is an act of privilege, it can never be a viable alternative to State obligations,said Dr James Obrinski, of the organisation Medicins sans Frontier, in Dhaka recently at the People’s Health Assembly (see Himal, February 2001). In a nutshell, industry and private donations are feel-good, short-term interventions and no substitute for the vastly larger, and essentially political, task of bringing health care to more than a billion poor people.

As another example, Bill Gates announced in November 2002 a massive donation of $100 million to India over ten years to fight AIDS there. It was big news and very welcome by many. Yet, at the same time he made that donation, he was making another larger donation—over $400 million, over three years—to increase support for Microsoft’s software development suite of applications and its platform, in competition with Linux52 and other rivals. Thomas Green, in a somewhat cynical article, questions who really benefits53, saying And being a monster MS [Microsoft] shareholder himself, a

(Emphasis is original.)Big Win

in India will enrich him [Bill Gates] personally, perhaps well in excess of the $100 million he’s donating to the AIDS problem. Makes you wonder who the real beneficiary of charity is here.

India has potentially one tenth of the world’s software developers, so capturing the market there of software development platforms is seen as crucial. This is just one amongst many examples of what appears extremely welcome philanthropy and charity also having other motives. It might be seen as horrible to criticize such charity, especially on a crucial issue such as AIDS, but that is not the issue. The concern is that while it is welcome that this charity is being provided, at a systemic level, such charity is unsustainable and shows ulterior motives. Would Bill Gates have donated that much had there not been additional interests for the company that he had founded?

In addition, as award-winning investigative reporter and author Greg Palast also notes54, the World Trade Organization’s Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the rule which helps Gates rule, also bars African governments from buying AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis medicine at cheap market prices.

He also adds that it is killing more people than the philanthropy saving. What Palast is hinting towards is the unequal rules of trade and economics that are part of the world system, that has contributed to countries such as most in Africa being unable to address the scourge of AIDS and other problems, even when they want to. See for example, the sections on free trade55, poverty56 and corporations57 on this web site for more.

The LA Times has also found that the Gates Foundation has been investing in questionable companies 58 that are often involved in environmental pollution, even child labor, and more.

In addition to private contributions, when it comes to government aid, these concerns can multiply as it may affect the economic and political direction of an entire nation if such government aid is also tied into political objectives that benefit the donor.

Are numbers the only issue?

The above talks a lot about numbers and attempts to address common questions about who gives what, as for Americans and Europeans, there is indeed a fascination of this topic.

Less mentioned in the media is that some aid money that is pledged often involves double accounting of sorts. Sometimes offers have even been reneged or just not delivered. This site’s section on the Asian tsunami disaster59 and on third world debt60 has more on these aspects.

It is common to hear many Americans claim that the US is the most generous country on earth. While the numbers above may say otherwise in a technical sense, is who gives the most

really the important discussion here? While important, concentrating on this one aspect diverts us from other pressing issues such as does the aid actually help the recipient, or does it actually help the donor.

As we will see further below, some aid has indeed been quite damaging for the recipient, while at the same time being beneficial for the donor.

The Changing Definition of Aid Reveals a much Deeper Decline than What Numbers Alone Can Show

The South Centre, mentioned earlier, notes that when the 0.7% of GNI promise for development aid was made in 1970, official development assistance was to be understood as bilateral grants and loans on concessional terms, and official contributions to multilateral agencies.

But, as they note, a number of factors have led to a large decline in aid, some that cannot be shown by numbers and graphs, alone. Factors include:

- Tighter budgetary constraints in richer countries during the 1980s;

- More importantly, an ideology shift on governments and markets (see also primer on neoliberalism61 and structural adjustment62 on this site);

- Increasing number of countries competing for development aid funds;

- Donors putting a broader interpretation on what constitutes development assistance.

On the last point above, South Centre notes that the broader interpretation include categories which bear little relationship to the need of the developing countries for long term development capital.

(Emphasis Added.) Thus, those expanded categories for official development assistance include:

- Debt relief;

- Subsidies on exports to developing countries;

- Food aid which disposes of agricultural surpluses resulting from government subsidies (see also this site’s section on food dumping and how it increases hunger and poverty63);

- Provision of surplus commodities of little economic value;

- Administrative costs;

- Payments for care and education of refugees in donor countries;

- Grants to NGOs and to domestic agencies to support emergency relief operations; and

- Technical co-operation grants which pay for the services of nationals of the donor countries.

An analysis of OECD data over time shows such increases in non-development aid:

In effect, not only has aid been way below that promised, but what has been delivered has not always been for the original goal of development.

The technical co-operation grants are also known as technical assistance. Action Aid, has been very critical about this and other forms of this broader interpretation which they have termed phantom aid

:

This year we estimate that $37 billion—roughly half of global aid—is

phantom aid, that is, it is not genuinely available to poor countries to fight poverty.… Nowhere is the challenge of increasing real aid as a share of overall aid greater than in the case of technical assistance. At least one quarter of donor budgets—some $19 billion in 2004—is spent in this way: on consultants, research and training. This is despite a growing body of evidence—much of it produced by donors themselves and dating back to the 1960s—that technical assistance is often overpriced and ineffective, and in the worst cases destroys rather than builds the capacity of the poorest countries.

… Although this ineffectiveness is an open secret within the development community, donors continue to insist on large technical assistance components in most projects and programmes they fund. They continue to use technical assistance as a

softlever to police and direct the policy agendas of developing country governments, or to create ownership of the kinds of reforms donors deem suitable. Donor funded advisers have even been brought in to draft supposedlycountry ownedpoverty reduction strategies.

The above report by Action Aid uses OECD data, as I have done. Their figures are based on 2004 data, which at time of their publication was the latest available. However, they also went further than I have to show just how much phantom aid there is. For example, they note (p.11) that the $37 billion of phantom aid in 2004 included:

- $6.9 billion (9% of all aid) not targeted for poverty reduction

- $5.7 billion (7%) double counted as debt relief

- $11.8 billion (15%) on over-priced, ineffective technical assistance

- $2.5 billion (3%) lost through aid tying

- $8.1 billion (10%) lost through poor donor co-ordination

- $2.1 billion (3%) on immigration related spending

- at least $70 (0.1%) million on excessive administration costs.

These figures are necessarily approximate, they note. If anything, they probably flatter donors. Lack of data means that other areas of

phantom aid

have been excluded from our analysis. These include conditional or unpredictable aid, technical assistance and administration spending through multilateral channels, security-related spending and emergency aid for reconstruction following conflicts in countries such as Iraq. Some of these forms of aid do little to fight poverty, and can even do more harm than good.

Action Aid also provided a matrix (p.14) showing the volumes of real and phantom aid by donor countries:

| High Real Aid Volume | Medium Real Aid Volume | Low Real Aid Volume | |

|---|---|---|---|

Source: Action Aid, Real Aid: Making Technical Assistance Work, July 5, 2006, p.14; OECD Figures for 2004 (latest at time of publication) | |||

| Low share of phantom aid |

| UK | |

| Medium share of phantom aid | Switzerland |

|

|

| High share of phantom aid |

|

| |

At the 2005 G8 Summit65, much was made about historic

debt write-offs and other huge amounts of aid. The problem, the media and government spin implied, was that rich country aid often gets wasted and will only be delivered to poor countries if they meet certain conditions and demands. Yet, hardly ever in the mainstream discourse is the quality of rich country aid an issue or problem that needs urgent addressing. The South Centre noted this many years ago:

The situation outlined above indicates a significant erosion in ODA in comparison with its original intent and content, and in relation to the 0.7 per cent target. It will no longer suffice to merely repeat that ODA targets should be fulfilled. What is required, in view of the policy trends in the North and the mounting need for and importance of concessional flows to a large number of countries in the South, is a fundamental and comprehensive review of the approaches by the international community to the question of concessional financial flows for development, covering the estimated needs, the composition and sources of concessional flows, the quantity and terms on which they are available, and the destination and uses.

Aid is Actually Hampering Development

Professor William Easterly, a noted mainstream economics professor on development and aid issues has criticized foreign aid for not having achieved much, despite grand promises:

[A tragedy of the world’s poor has been that] the West spent $2.3 trillion on foreign aid over the last five decades and still had not managed to get twelve-cent medicines to children to prevent half of all malaria deaths. The West spent $2.3 trillion and still had not managed to get four-dollar bed nets to poor families. The West spent $2.3 trillion and still had not managed to get three dollars to each new mother to prevent five million child deaths.

… It is heart-breaking that global society has evolved a highly efficient way to get entertainment to rich adults and children, while it can’t get twelve-cent medicing to dying poor children.

The United Nations Economic and Social Council, when noting that effectiveness of aid to poor countries requires a focus on economic infrastructure67, also noted that ODA was hampering aid. Jose Antonio Ocampo, Under-Secretary-General for the United Nations Economic and Social Affairs said that debt68, commodities69, official development assistance and, in some cases, the risk of conflict is hampering development in the least developed countries.

See also, for example, the well-regarded Reality of Aid70 project for more on the reality and rhetoric of aid. This project looks at what various nations have donated, and how and where it has been spent, etc.

Private flows often do not help the poorest

While ODA’s prime purpose is to promote development, private flows are often substantially larger than ODA. During economic booms, more investment is observed in rapidly emerging economies, for example. But this does not necessarily mean the poorest nations get such investment.

During the boom of the mid-2000s before the global financial crisis71 sub-Saharan Africa did not attract as much investment from the rich nations, for example (though when China decided to invest in Africa, rich nations looked on this suspiciously fearing exploitation, almost ignoring their own decades of exploitation of the continent. China’s interest is no-doubt motivated by self-interest, and time will have to tell whether there is indeed exploitation going on, or if African nations will be able to demand fair conditions or not).

As private flows to developing countries from multinational companies and investment funds reflect the interests of investors, the importance of Overseas Development Assistance cannot be ignored.

Furthermore, (and detailed below) these total flows are less than the subsidies many of the rich nations give to some of their industries, such as agriculture, which has a direct impact on the poor nations (due to flooding the market with—or dumping72—excess products, protecting their own markets from the products of the poor countries, etc.)

In addition, a lot of other inter-related issues, such as geopolitics, international economics, etc all tie into aid, its effectiveness and its purpose. Africa is often highlighted as an area receiving more aid, or in need of more of it, yet, in recent years, it has seen less aid and less investment etc, all the while being subjected to international policies and agreements that have been detrimental to many African people.

For the June 2002 G8 summit, a briefing was prepared by Action for Southern Africa and the World Development Movement, looking at the wider issue of economic and political problems:

It is undeniable that there has been poor governance, corruption and mismanagement in Africa. However, the briefing reveals the context—the legacy of colonialism, the support of the G8 for repressive regimes in the Cold War, the creation of the debt trap, the massive failure of Structural Adjustment Programmes imposed by the IMF and World Bank and the deeply unfair rules on international trade. The role of the G8 in creating the conditions for Africa’s crisis cannot be denied. Its overriding responsibility must be to put its own house in order, and to end the unjust policies that are inhibiting Africa’s development.

As the above briefing is titled, a common theme on these issues (around the world) has been to blame the victim

. The above briefing also highlights some common myths

often used to highlight such aspects, including (and quoting):

- Africa has received increasing amounts of aid over the years—in fact, aid to Sub-Saharan Africa fell by 48% over the 1990s

- Africa needs to integrate more into the global economy—in fact, trade accounts for larger proportion of Africa’s income than of the G8

- Economic reform will generate new foreign investment—in fact, investment to Africa has fallen since they opened up their economies

- Bad governance has caused Africa’s poverty—in fact, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), economic conditions imposed by the IMF and the World Bank were the dominant influence on economic policy in the two decades to 2000, a period in which Africa’s income per head fell by 10% and income of the poorest 20% of people fell by 2% per year

Christian Aid weighs in on this with a more recent report noting that sub-Saharan Africa is a massive $272 billion worse off because of free

trade policies forced on them as a condition of receiving aid and debt relief.75 They also note that:

The reforms that rich countries forced on Africa were supposed to boost economic growth. However, the reality is that imports increased massively while exports went up only slightly. The growth in exports only partially compensated African producers for the loss of local markets and they were left worse off.

The quantity issue is an input into the aid process. The quality is about the output. We see from the above then, that the quantity of aid has not been as much as it should be. But what about the quality of the aid?

Aid as a foreign policy tool to aid the donor not the recipient

Aid appears to have established as a priority the importance of influencing domestic policy in the recipient countries

As shown throughout this web site (and hundreds of others) one of the root causes of poverty lies in the powerful nations that have formulated most of the trade and aid policies today, which are more to do with maintaining dependency on industrialized nations, providing sources of cheap labor and cheaper goods for populations back home and increasing personal wealth, and maintaining power over others in various ways. As mentioned in the structural adjustment77 section, so-called lending and development schemes have done little to help poorer nations progress.

The US, for example, has also held back dues to the United Nations, which is the largest body trying to provide assistance in such a variety of ways to the developing countries. Former US President Jimmy Carter describes the US as stingy

:

While the US provided large amounts of military aid to countries deemed strategically important, others noted that the US ranked low among developed nations in the amount of humanitarian aid it provided poorer countries.

We are the stingiest nation of all,former President Jimmy Carter said recently in an address at Principia College in Elsah, Ill.

Evan Osbourne, writing for the Cato Institute, also questioning the effectiveness of foreign aid79 and noted the interests of a number of other donor countries, as well as the U.S., in their aid strategies in past years. For example:

- The US has directed aid to regions where it has concerns related to its national security, e.g. Middle East, and in Cold War times in particular, Central America and the Caribbean;

- Sweden has targetted aid to

progressive societies

; - France has sought to promote maintenance or preserve and spread of French culture, language, and influence, especially in West Africa, while disproportionately giving aid to those that have extensive commercial ties with France;

- Japan has also heavily skewed aid towards those in East Asia with extensive commercial ties together with conditions of Japanese purchases;

Osbourne also added that domestic pressure groups (corporate lobby groups, etc) have also proven quite adept at steering aid to their favored recipients.

And so, If aid is not particularly given with the intention to foster economic growth, it is perhaps not surprising that it does not achieve it.

Aid And Militarism

IPS noted that recent US aid has taken on militaristic angles as well, following similar patterns to aid during the cold war80. The war on terrorism is also having an effect as to what aid goes where and how much is spent.

For example:

Credits for foreign militaries to buy US weapons and equipment would increase by some 700 million dollars to nearly five billion dollars, the highest total in well over a decade.

(This is also an example of aid benefiting the donor!)The total foreign aid proposal … amounts to a mere five percent of what Bush is requesting for the Pentagon next year.

Bush’s foreign-aid plan [for 2005] actually marks an increase over 2004 levels, although much of the additional money is explained by greater spending on security for US embassies and personnel overseas.

As in previous years, Israel and Egypt are the biggest bilateral recipients under the request, accounting for nearly five billion dollars in aid between them. Of the nearly three billion dollars earmarked for Israel, most is for military credits.

- This militaristic aid will come

largely at the expense of humanitarian and development assistance.

The European Union is linking aid to fighting terrorism81 as well, with European ministers warning countries that their relations with the economically powerful bloc will suffer if they fail to cooperate in the fight against terrorism. An EU official is quoted as saying, aid and trade could be affected if the fight against terrorism was considered insufficient

, leading to accusations of compromising the neutrality, impartiality and independence of humanitarian assistance

.

Aid Money Often Tied to Various Restrictive Conditions

As a condition for aid money, many donors apply conditions that tie the recipient to purchase products only from that donor. In a way this might seem fair and balanced

, because the donor gets something out of the relationship as well, but on the other hand, for the poorer country, it can mean precious resources are used buying more expensive options, which could otherwise have been used in other situations. Furthermore, the recipient then has less control and decision-making on how aid money is spent. In addition the very nations that typically promote free-markets and less government involvement in trade, commerce, etc., ensure some notion of welfare for some of their industries.

IPS noted that aid tied with conditions cut the value of aid to recipient countries by some 25-40 percent, because it obliges them to purchase uncompetitively priced imports from the richer nations. IPS was citing a UN Economic Council for Africa study82 which also noted that just four countries (Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom) were breaking away from the idea of tied aid

with more than 90 percent of their aid untied

.

In addition, IPS noted the following, worth quoting at length:

[Njoki Njoroge] Njehu [director of the 50 Years is Enough campaign] cited the example of Eritrea, which discovered it would be cheaper to build its network of railways with local expertise and resources rather than be forced to spend aid money on foreign consultants, experts, architects and engineers imposed on the country as a condition of development assistance.

Strings attached to US aid for similar projects, she added, include the obligation to buy products such as Caterpillar and John Deere tractors.

All this adds up to the cost of the project.Njehu also pointed out that money being doled out to Africa to fight HIV/AIDS is also a form of tied aid. She said Washington is insisting that the continent’s governments purchase anti-AIDS drugs from the United States instead of buying cheaper generic products from South Africa, India or Brazil.

As a result, she said, US brand name drugs are costing up to 15,000 dollars a year compared with 350 dollars annually for generics.

…

AGOA [African Growth and Opportunity Act, signed into US law in 2000] is more sinister than tied aid, says Njehu.

If a country is to be eligible for AGOA, it has to refrain from any actions that may conflict with the US’sstrategic interests.

The potential of this clause to influence our countries' foreign policies was hinted at during debates at the United Nations over the invasion of Iraq,she added.

The war against Iraq was of strategic interest to the United States,Njehu said. As a result, she said, several African members of the UN Security Council, including Cameroon, Guinea and Angola, were virtually held to ransom when the United States was seeking council support for the war in 2003.

They came under heavy pressure,she said.The message was clear: either you vote with us or you lose your trade privileges.

As noted further above, almost half of all foreign aid can be considered phantom aid

, aid which does not help fight poverty, and is based on a broader definition of foreign aid that allows double counting and other problems to occur. Furthermore, some 50% of all technical assistance is said to be wasted because of inappropriate usage on expensive consultants, their living expenses, and training (some $11.8 billion).

In their 2000 report looking back at the previous year, the Reality of Aid 2000 (Earthscan Publications, 2000, p.81), reported in their US section that 71.6% of its bilateral aid commitments were tied to the purchase of goods and services from the US.

That is, where the US did give aid, it was most often tied to foreign policy objectives that would help the US.

Leading up to the UN Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey, Mexico in March 2002, the Bush administration promised a nearly $10 billion fund over three years followed by a permanent increase of $5 billion a year thereafter. The EU also offered some $5 billion increase over a similar time period.

While these increases have been welcome, these targets are still below the 0.7% promised at the Earth summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The World Bank have also leveled some criticism of past policies:

Commenting on the latest US pledge [of $10 billion], Julian Borger and Charlotte Denny of the Guardian (UK) say Washington is desperate to deflect attention in Monterrey from the size of its aid budget. But for more generous donors, says the story, Washington’s conversion to the cause of effective aid spending is hard to swallow. Among the big donors, the US has the worst record for spending its aid budget on itself—70 percent of its aid is spent on US goods and services. And more than half is spent in middle income countries in the Middle East. Only $3bn a year goes to South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

In addition, promises of more money were tied to more conditions, which for many developing countries is another barrier to real development, as the conditions are sometimes favorable to the donor, not necessarily the recipient. Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment commented on the US conditional pledge of more money that:

Thus, status quo in world relations is maintained. Rich countries like the US continue to have a financial lever to dictate what good governance means and to pry open markets of developing countries for multinational corporations. Developing countries have no such handle for Northern markets, even in sectors like agriculture and textiles, where they have an advantage but continue to face trade barriers and subsidies. The estimated annual cost of Northern trade barriers to Southern economies is over US $100 billion, much more than what developing countries receive in aid.

As discussed further on this site’s section on water issues86, the World Development Movement campaign organization reported in early 2005 that the British government has been using aid money to pay British companies to push privatization of water services to poor countries, even though it may not be in their best interests.

The 2005 G8 Summit at Gleneagles in Scotland87 saw promises of lots of aid and debt relief, but these were accompanied with a lot of spin, and more conditions, often considered harmful in the past.

Another aspect of aid tying into interests of donors is exemplified with climate change negotiations. Powerful nations such as the United States have been vocally against the Kyoto Protocol on climate change. Unlike smaller countries, they have been able to exert their influence on other countries to push for bilateral agreements conditioned with aid, in a way that some would describe as a bribe. Center for Science and Environment for example criticizes such politics:

It is easy to be taken in with promises of bilateral aid, and make seemingly innocuous commitments in bilateral agreements. There is far too much at stake here [with climate change]. To further their interests, smaller, poorer countries don’t have aid to bribe and trade muscle to threaten countries.

This use of strength in political and economic arenas is nothing new. Powerful nations have always managed to exert their influence in various arenas. During the Gulf War in 1991 for example, many that ended up in the allied coalition were promised various concessions behind the scenes (what the media described as diplomacy

). For example, Russia was offered massive IMF money. Even now, with the issue of the International Criminal Court, which the US is also opposed to, it has been pressuring other nations on an individual basis to not sign, or provide concessions. In that context, aid is often tied to political objectives and it can be difficult to sometimes see when it is not so.

But some types of conditions attached to aid can also be ideologically driven. For example, quoted further above by the New York Times, James Wolfensohn, the World Bank president noted how European and American farm subsidies are crippling Africa’s chance to export its way out of poverty.

While this criticism comes from many perspectives, Wolfensohn’s note on export also suggests that some forms of development assistance may be on the condition that nations reform their economies to certain ideological positions. Structural Adjustment has been one of these main policies as part of this neoliberal ideology, to promote export-oriented development in a rapidly opened economy. Yet, this has been one of the most disastrous policies89 in the past two decades, which has increased poverty. Even the IMF and World Bank have hinted from time to time that such policies are not working. People can understand how tying aid on condition of improving human rights, or democracy might be appealing, but when tied to economic ideology, which is not always proven, or not always following the one size fits all

model, the ability (and accountability) of decisions that governments would have to pursue policies they believe will help their own people are reduced.

More Money Is Transferred From Poor Countries to Rich, Than From Rich To Poor

For the OECD countries to meet their obligations for aid to the poorer countries is not an economic problem. It is a political one. This can be seen in the context of other spending. For example,

- The US recently increased90 its military budget by some $100 billion dollars alone

- Europe subsidizes its agriculture to the tune of some $35-40 billion per year, even while it demands other nations to liberalize their markets to foreign competition.

- The US also introduced a $190 billion dollar subsidy to its farms through the US Farm Bill, also criticized as a protectionist measure.

- While aid amounts to around $70 to 100 billion per year, the poor countries pay some $200 billion to the rich each year.

- There are many more (some mentioned below too).

In effect then, there is more aid to the rich than to the poor.

While the amount of aid from some countries such as the US might look very generous in sheer dollar terms (ignoring the percentage issue for the moment), the World Bank also pointed out91 that at the World Economic Forum in New York, February 2002, [US Senator Patrick] Leahy noted that two-thirds of US government aid goes to only two countries: Israel and Egypt. Much of the remaining third is used to promote US exports or to fight a war against drugs that could only be won by tackling drug abuse in the United States.

In October 2003, at a United Nations conference, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan noted that

developing countries made the sixth consecutive and largest ever transfer of funds to

other countriesin 2002, a sum totallingalmost $200 billion.

Funds should be moving from developed countries to developing countries, but these numbers tell us the opposite is happening…. Funds that should be promoting investment and growth in developing countries, or building schools and hospitals, or supporting other steps towards the Millennium Development Goals, are, instead, being transferred abroad.

And as Saradha Lyer, of Malaysia-based Third World Network notes, instead of promoting investment in health, education, and infrastructure development in the third world, this money has been channelled to the North, either because of debt servicing arrangements, asymmetries and imbalances in the trade system or because of inappropriate liberalization and privatization measures 93 imposed upon them by the international financial and trading system.

This transfer from the poorer nations to the rich ones makes even the recent increase in ODA seem little in comparison.

Aid Amounts Dwarfed by Effects of First World Subsidies, Third World Debt, Unequal Trade, etc

Combining the above mentioned reversal of flows with the subsidies and other distorting mechanisms, this all amounts to a lot of money being transferred to the richer countries (also known as the global North), compared to the total aid amounts that goes to the poor (or South).

As well as having a direct impact on poorer nations, it also affects smaller farmers in rich nations. For example, Oxfam, criticizing EU double standards, highlights the following:

Latin America is the worst-affected region, losing $4bn annually from EU farm policies. EU support to agriculture is equivalent to double the combined aid budgets of the European Commission and all 15 member states. Half the spending goes to the biggest 17 per cent of farm enterprises, belying the manufactured myth that the CAP [Common Agriculture Policy] is all about keeping small farmers in jobs.

And as Devinder Sharma adds, some of the largest benefactors of European agricultural subsidies include the Queen of England, and other royalties in Europe 95!

The double standards that Oxfam mentions above, and that countless others have highlighted has a huge impact on poor countries, who are pressured to follow liberalization and reducing government interference

while rich nations are able to subsidize some of their industries. Poor countries consequently have an even tougher time competing. IPS captures this well:

On the one hand, OECD countries such as the US, Germany or France continue through the ECAs [export credit agencies] to subsidise exports with taxpayers' money, often in detriment to the competitiveness of the poorest countries of the world,says [NGO Environment Defence representative, Aaron] Goldzimmer.On the other hand, the official development assistance which is one way to support the countries of the South to find a sustainable path to development and progress is being reduced.…

Government subsidies mean considerable cost reduction for major companies and amount to around 10 per cent of annual world trade. In the year 2000, subsidies through ECAs added up to 64 billion dollars of exports from industrialised countries, well above the official development assistance granted last year of 51.4 billion dollars.

As well as agriculture, textiles and clothing is another mainstay of many poor countries. But, as with agriculture, the wealthier countries have long held up barriers to prevent being out-competed by poorer country products. This has been achieved through things like subsidies and various agreements

. The impact to the poor has been far-reaching, as Friends of the Earth highlights:

Despite the obvious importance of the textile and clothing sectors in terms of development opportunities, the North has consistently and systematically repressed developing country production to protect its own domestic clothing industries.

Since the 1970s the textile and clothing trade has been controlled through the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) which sets bilateral quotas between importing and exporting countries. This was supposedly to protect the clothing industries of the industrialised world while they adapted to competition from developing countries. While there are cases where such protection may be warranted, especially for transitionary periods, the MFA has been in place since 1974 and has been extended five times. According to Oxfam, the MFA is,

…the most significant..[non tariff barrier to trade]..which has faced the world’s poorest countries for over 20 years.Although the MFA has been replaced by the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) which phases out support over a further ten year period—albeit through a process which in itself is highly inequitable—developing countries are still suffering the consequences. The total cost to developing countries of restrictions on textile imports into the developed world has been estimated to be some $50 billion a year. This is more or less equivalent to the total amount of annual development assistance provided by Northern governments to the Third World.

There is often much talk of trade rather than aid, of development, of opening markets etc. But, when at the same time some of the important markets of the US, EU and Japan appear to be no-go areas for the poorer nations, then such talk has been criticized by some as being hollow. The New York Times is worth quoting at length:

Our compassion [at the 2002 G8 Summit talking of the desire to help Africa] may be well meant, but it is also hypocritical. The US, Europe and Japan spend $350 billion each year on agricultural subsidies (seven times as much as global aid to poor countries), and this money creates gluts that lower commodity prices and erode the living standard of the world’s poorest people.

These subsidies are crippling Africa’s chance to export its way out of poverty,said James Wolfensohn, the World Bank president, in a speech last month.Mark Malloch Brown, the head of the United Nations Development Program, estimates that these farm subsidies cost poor countries about $50 billion a year in lost agricultural exports. By coincidence, that’s about the same as the total of rich countries' aid to poor countries, so we take back with our left hand every cent we give with our right.

It’s holding down the prosperity of very poor people in Africa and elsewhere for very narrow, selfish interests of their own,Mr. Malloch Brown says of the rich world’s agricultural policy.It also seems a tad hypocritical of us to complain about governance in third-world countries when we allow tiny groups of farmers to hijack billion of dollars out of our taxes.

In fact, J. Brian Atwood, stepped down in 1999 as head of the US foreign aid agency, USAID. He was very critical of US policies, and vented his frustration that despite many well-publicized trade missions, we saw virtually no increase of trade with the poorest nations. These nations could not engage in trade because they could not afford to buy anything.

(Quoted from a speech99 that he delivered to the Overseas Development Council100.)

As Jean-Bertrand Arisitde also points out, there is also a boomerang effect of loans as large portions of aid money is tied to purchases of goods and trade with the donor:

Many in the first world imagine the amount of money spent on aid to developing countries is massive. In fact, it amounts to only 0.3% of GNP of the industrialized nations. In 1995, the director of the US aid agency defended his agency by testifying to his congress that 84 cents of every dollar of aid goes back into the US economy in goods and services purchased. For every dollar the United States puts into the World Bank, an estimated $2 actually goes into the US economy in goods and services. Meanwhile, in 1995, severely indebted low-income countries paid one billion dollars more in debt and interest to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) than they received from it. For the 46 countries of Subsaharan Africa, foreign debt service was four times their combined governmental health and education budgets in 1996. So, we find that aid does not aid.

In other words, often aid does not aid the recipient, it aids the donor. For the US in the above example, its aid agency has been a foreign policy tool to enhance its own interests, successfully.

And then there has been the disastrous food aid policies, which is another example of providing aid but using that aid as an arm of foreign policy objectives. It has helped their corporations and large farmers at a huge cost to developing countries, and has seen an increase in hunger, not reduction. For more details, see the entire section on this site that discusses this, in the Poverty and Food Dumping101 part of this web site.

For the world’s hungry, however, the problem isn’t the stinginess of our aid. When our levels of assistance last boomed, under Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s, the emphasis was hardly on eliminating hunger. In 1985, Secretary of State George Shultz stated flatly that

our foreign assistance programs are vital to the achievement of our foreign policy goals.But Shultz’s statement shouldn’t surprise us. Every country’s foreign aid is a tool of foreign policy. Whether that aid benefits the hungry is determined by the motives and goals of that policy—by how a government defines the national interest.

The above quote from the book World Hunger is from Chapter 10, which is also reproduced in full on this web site102. It also has more facts and stats on US aid and foreign policy objectives, etc.

As an aside, it is interesting to note the disparities between what the world spends on military, compared to other international obligations and commitments. Most wealthy nations spend far more on military than development103, for example. The United Nations, which gets its monies from member nations, spends about $10 billion—or about 3% of what just the US alone spends on its military. It is facing a financial crisis104 as countries such as the US want to reduce their burden of the costs—which comparatively is quite low anyway—and have tried to withhold payments or continued according to various additional conditions.

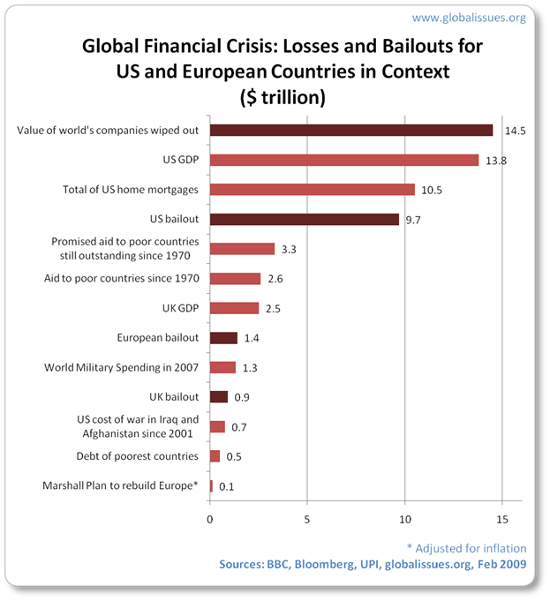

And with the recent financial crisis, clearly the act of getting resources together is not the issue, as far more has been made available in just a few short months than an entire 4 decades of aid:

But, as the quote above highlights as well, as well as the amount of aid, the quality of aid is important. (And the above highlights that the quality has not been good either.)

But aid could be beneficial

Government aid, from the United States and others, as indicated above can often fall foul of political agendas and interests of donors. At the same time that is not the only aid going to poor countries. The US itself, for example, has a long tradition of encouraging charitable contributions. Indeed, tax laws in the US and various European countries are favorable to such giving as discussed further above. But private funding, philanthropy and other sources of aid can also fall foul of similar or other agendas, as well as issues of concentration on some areas over others, of accountability, and so on. (More on these aspects is introduced on this site’s NGO and Development section105.)

Trade and Aid

Oxfam highlights the importance of trade and aid:

Some Northern governments have stressed that

trade not aidshould be the dominant theme at the [March 2002 Monterrey] conference [on Financing for Development]. That approach is disingenuous on two counts. First, rich countries have failed to open their markets to poor countries. Second, increased aid is vital for the world’s poorest countries if they are to grasp the opportunities provided through trade.

In addition to trade not aid

perspectives, the Bush Administration was keen to push for grants rather than loans from the World Bank. Grants being free money appears to be more welcome, though many European nations aren’t as pleased with this option. Furthermore, some commentators point out that the World Bank, being a Bank, shouldn’t give out grants, which would make it compete with other grant-offering institutions such as various other United Nations bodies. Also, there is concern that it may be easier to impose political conditions to the grants. John Taylor, US Undersecretary of the Treasury, in a recent speech in Washington also pointed out that Grants are not free. Grants can be easily be tied to measurable performance or results.

Some comment that perhaps grants may lead to more dependencies as well as some nations may agree to even more conditions regardless of the consequences, in order to get the free money. (More about the issue of grants is discussed by the Bretton Woods Project107.)

In discussing trade policies of the US, and EU, in relation to its effects on poor countries, chief researcher of Oxfam, Kevin Watkins, has been very critical, even charging them with hypocrisy for preaching free trade but practicing mercantilism:

Looking beyond agriculture, it is difficult to avoid being struck by the discrepancy between the picture of US trade policy painted by [US Trade Representative, Robert] Zoellick and the realities facing developing countries.

To take one example, much has been made of America’s generosity towards Africa under the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). This provides what, on the surface, looks like free market access for a range of textile, garment and footwear products. Scratch the surface and you get a different picture. Under AGOA’s so-called rules-of-origin provisions, the yarn and fabric used to make apparel exports must be made either in the United States or an eligible African country. If they are made in Africa, there is a ceiling of 1.5 per cent on the share of the US market that the products in question can account for. Moreover, the AGOA’s coverage is less than comprehensive. There are some 900 tariff lines not covered, for which average tariffs exceed 11%.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the benefits accruing to Africa from the AGOA would be some $420m, or five times, greater if the US removed the rules-of-origin restrictions. But these restrictions reflect the realities of mercantilist trade policy. The underlying principle is that you can export to America, provided that the export in question uses American products rather than those of competitors. For a country supposedly leading a crusade for open, non-discriminatory global markets, it’s a curiously anachronistic approach to trade policy.