Global Health Overview

Author and Page information

This print version has been auto-generated from https://www.globalissues.org/article/588/global-health-overview

This article was originally written, on request, for Risk Group LLC, for their December 2005 edition on health care risks. It has been reposted here, reformatted for this web site, and as with most articles on this site, has and will be updated more as time allows.

This article looks at some global aspects of health issues, such as the impact of poverty and inequality, the nature of patent rules at the WTO, pharmaceutical company interests, as well as some global health initiatives and the changing nature of the global health problems being faced.

This article looks at some global aspects of health issues, such as the impact of poverty and inequality, the nature of patent rules at the WTO, pharmaceutical company interests, as well as some global health initiatives and the changing nature of the global health problems being faced.

On this page:

- Millions die each year, needlessly

- Health, poverty and inequality

- Structural Adjustment—Cutting back on vital health and education services

- Large Pharmaceutical Companies—Profit at all costs?

- WTO—Patents, Intellectual Property, Emergency Drugs and Developing Countries

- Global Health Initiatives

- Increasing commodification and commercialization of healthcare

- Changing Dynamics in Global Health Issues and Priorities

- Summary

Millions die each year, needlessly

Despite incredible improvements in health since 1950, there are still a number of challenges, which should have been easy to solve. Consider the following:

- One billion people lack access to health care systems1

-

36 million deaths each year are caused by noncommunicable diseases

2, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic lung diseases. This is almost two-thirds of the estimated 56 million deaths each year worldwide. (A quarter of these take place before the age of 60.)

Breaking down the leading causes a bit further (there are others too),

- Cardiovascular diseases cause about 17 million deaths

- Cancers, about 7.6 million deaths

- Chronic lung diseases, about 4.2 million deaths

- Diabetes, about 1.3 million deaths

- Over 7.5 million children under the age of 5 die from malnutrition and mostly preventable diseases, each year3

- In 2008, some 6.7 million people died of infectious diseases4 alone, far more than the number killed in the natural or man-made catastrophes that make headlines. (These are the latest figures presented by the World Health Organization.)

-

AIDS/HIV has spread rapidly. UNAIDS estimates5 for 2008 that there were roughly:

- 33.4 million living with HIV

- 2.7 million new infections of HIV

- 2 million deaths from AIDS

- Tuberculosis kills 1.7 million people each year6, with 9.4 million new cases a year.

- 1.6 million people still die from pneumococcal diseases every year7, making it the number one vaccine-preventable cause of death worldwide. More than half of the victims are children. (The pneumococcus is a bacterium that causes serious infections like meningitis, pneumonia and sepsis. In developing countries, even half of those children who receive medical treatment will die. Every second surviving child will have some kind of disability.)

- Malaria causes some 225 million acute illnesses and over 780,000 deaths, annually 8

- 164,000 people, mostly children under 5, died from measles in 20089 (the latest years for which figures are available, at time of writing) even though effective immunization, which includes vaccine and safe injection equipment, costs less than 1 US dollars and has been available for more than 40 years.

These and other diseases kill more people each year than conflict alone.

Why has it got to such a level when the world has enough wealth to help address most of these problems, or at least alleviate more of the suffering?

This article looks at a number of global factors and issues around health problems.

Health, poverty and inequality

Although the statistics above make for grim reading, an important underlying cause of all these deaths is poverty. The World Health Organization (WHO) and others repeatedly point out that many of these diseases are diseases of poverty.

However, some diseases are now not only the result of poverty, but have been contributing to poverty—a nasty feedback loop. In the case of malaria, for instance, the WHO notes that,

Malaria has significant measurable direct and indirect costs, and has recently been shown to be a major constraint to economic development.

… Annual economic growth in countries with high malaria transmission has historically been lower than in countries without malaria. Economists believe that malaria is responsible for a

growth penaltyof up to 1.3% per year in some African countries.… The indirect costs of malaria include lost productivity or income associated with illness or death.

… Malaria has a greater impact on Africa’s human resources than simple lost earnings. Although difficult to express in dollar terms, another indirect cost of malaria is the human pain and suffering caused by the disease. Malaria also hampers children’s schooling and social development through both absenteeism and permanent neurological and other damage associated with severe episodes of the disease.

The simple presence of malaria in a community or country also hampers individual and national prosperity due to its influence on social and economic decisions. The risk of contracting malaria in endemic areas can deter investment, both internal and external and affect individual and household decision making in many ways that have a negative impact on economic productivity and growth.

The following video details how malaria affects so many in Ethiopia, in turn highlighting numerous related issues such as the impact of poverty. The topics discussed in this video also apply to numerous regions around the world face—Africa in particular:

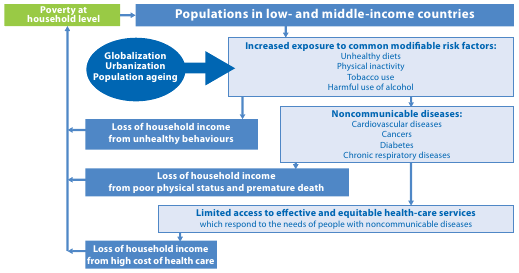

While explaining how noncommunicable diseases are the the leading causes of death globally, killing more people each year than all other causes combined, the World Health Organization adds that,

Contrary to popular opinion, available data demonstrate that nearly 80% of NCD [noncommunicable disease] deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.

…

NCDs are caused, to a large extent, by four behavioral risk factors that are pervasive aspects of economic transition, rapid urbanization and 21st-century lifestyles: tobacco use, unhealthy diet, insufficient physical activity and the harmful use of alcohol.

The greatest effects of these risk factors fall increasingly on low- and middle-income countries, and on poorer people within all countries, mirroring the underlying socioeconomic determinants.

Among these populations, a vicious cycle may ensue: poverty exposes people to behavioral risk factors for NCDs and, in turn, the resulting NCDs may become an important driver to the downward spiral that leads families towards poverty.

Impact on development, and Chapter 2)

In the same report, the WHO provides a useful diagram:

At the end of August, 2008, the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health15 presented a 3-year investigation into the social detriments to health in a report titled the Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health16.

The report noted that health inequalities were to be found all around the world, not just the poorest countries, but even in wealthy nations such as the UK. The greater the social disadvantage, the worse the health

, the report says (p.31).

The poorest of the poor, around the world, have the worst health. Those at the bottom of the distribution of global and national wealth, those marginalized and excluded within countries, and countries themselves disadvantaged by historical exploitation and persistent inequity in global institutions of power and policy-making present an urgent moral and practical focus for action. But focusing on those with the least, on the ‘gap’ between the poorest and the rest, is only a partial response.

… In rich countries, low socioeconomic position means poor education, lack of amenities, unemployment and job insecurity, poor working conditions, and unsafe neighbourhoods, with their consequent impact on family life. These all apply to the socially disadvantaged in low-income countries in addition to the considerable burden of material deprivation and vulnerability to natural disasters. So these dimensions of social disadvantage – that the health of the worst off in high-income countries is, in a few dramatic cases, worse than average health in some lower-income countries … – are important for health.

Sir Michael Marmot, chair of the Commission, noted in an interview that most health problems are due to social, political and economic factors.

The key determinants of health of individuals and populations are the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work and age,

he says. And those circumstances are affected by the social and economic environment. They are the premature cause of disease and suffering; that’s unnecessary. And that’s why we say a toxic combination of poor social policies, bad politics and unfair economics are causing health and disease on a grand scale.

Marmot expands on this further in the video clip.

Even within a country such as the UK, then, the report finds that the average life-span can differ by some 28 years, depending on whether you are in the poorer or wealthier strata of society.

Mirai Chatterjee, coordinator of Social Security for the Indian women’s organization, SEWA, also explains how health is inextricably linked to economic issues. Without work, health cannot be afforded; Without good health, work cannot be done.

Similarly, a Canadian study found that better health enables more people to participate in the economy and reducing the costs of lost productivity by only 10-20% could add billions of dollars to the Canadian economy. (p. 39)

To begin to address these health issues, the commission suggested 3 principles of action:

- Improve the conditions of daily life—the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age

- Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources—the structural drivers of those conditions of daily life—globally, nationally, and locally.

- Measure the problem, evaluate action, expand the knowledge base, develop a workforce that is trained in the social determinants of health, and raise public awareness about the social determinants of health.

The report also adds that It is important to note here that the commission, while talking about health issues, finds that most health problems are caused not by health issues as such, but by social, political and economic conditions that drives our lives.

(Emphasis added.)

Structural Adjustment—Cutting back on vital health and education services

Economic policies, such as Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), enforced by the IMF and World Bank for decades on poor countries have had a disastrous effect on health. SAPs were designed as an economic measure to promote fiscal austerity for poor countries that were burdened with heavy debt repayments to the rich countries. With the economic and third world debt crisis in the 1970s and 1980s, developing countries were pressured to take on Structural Adjustment. Economies were restructured to ensure debt repayment to the rich countries, but this meant reducing the standards of living for most people. Side NoteThat much of third world debt20 has been considered odious debt, is another issue in its own right!

The typical prescription to this economic medicine included:

- Privatization at all costs;

- Capital market liberalization;

- Market-based pricing; and

- Free Trade.

Regardless of specific circumstances, almost all developing countries were handed the same medicine.

As former World Bank Chief Economist and Nobel Prize winner for economics, Joseph Stiglitz noted, the IMF typically handed out these policies with a blind allegiance to market fundamentalism.

This had a number of effects:

- Poor countries, typically without fully developed market economies, were driven into further poverty as state protection and nurturing of domestic industries were abandoned, leaving the country open to foreign takeover of key services and sectors;

- Cost of food, health services, education and other critical functions went up as important subsidies and other such programs were removed;

- Social unrest, or as Stiglitz called it,

IMF riots

occurred as the cost of living became unbearable - Barriers to trade were removed, but in its place were the WTO rules, which favor the rich countries.

In terms of health, services were reduced or removed, and now health care is either unavailable for the poor in many parts of the world, or is too expensive. As noted above, 1 billion lack access to health care.

In Africa, for example,

The health care systems inherited by most African states after the colonial era were unevenly weighted toward privileged elites and urban centers. In the 1960s and 1970s, substantial progress was made…. Most African governments increased spending on the health sector during this period. They endeavored to extend primary health care and to emphasize the development of a public health system to redress the inequalities of the colonial era.

… With the economic crisis of the 1980s, much of Africa’s economic and social progress over the previous two decades began to come undone. As African governments became clients of the World Bank and IMF, they forfeited control over their domestic spending priorities. The loan conditions of these institutions forced contraction in government spending on health and other social services.

… The economic austerity policies attached to World Bank and IMF loans led to intensified poverty in many African countries in the 1980s and 1990s. This increased the vulnerability of African populations to the spread of diseases and to other health problems.

... Declining living conditions and reduced access to basic services have led to decreased health status. In Africa today, almost half of the population lacks access to safe water and adequate sanitation services. As immune systems have become weakened, the susceptibility of Africa’s people to infectious diseases has greatly increased.

… Even as government spending on health was cut back, the amounts being paid by African governments to foreign creditors continued to increase. By the 1990s, most African countries were spending more on repaying foreign debts than on health or education for their people. Health care services in African countries disintegrated, while desperately needed resources were siphoned off by foreign creditors…. Across Africa, debt repayments compete directly with spending on Africa’s health care services.

Despite these problems, the recommended solution by the IMF and others was privatization of the health system. For Africa, however, and many other poor countries, this was not appropriate.

A study of 21 post-communist Eastern European and former Soviet countries found that IMF economic reform programs are associated with significantly worsened tuberculosis incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates 22 in those countries, independent of other political, socioeconomic, demographic, and health changes in these countries. Future research, the authors noted, should attempt to examine how IMF programs may have related to other non-tuberculosis–related health outcomes in those countries.

Even in most developed countries, health is accepted as a fundamental human right, not a privilege, and is indeed enshrined in the UN Declaration of Human Rights23 (see Article 25, paragraph 1.) A solely market-based system for health services is even resisted, therefore, in some of the richest countries in the world. Canada, Australia, and many European nations, for example, boast rich public health systems, though some are under pressure to privatize at least partly, as well. Even in the US, where a privatized health system is generally in place, some 45 million people were without health insurance in 200324. If the rich countries are struggling on this issue, for poorer countries, it is even harder:

Throughout Africa, the privatization of health care has reduced access to necessary services. The introduction of market principles into health care delivery has transformed health care from a public service to a private commodity. The outcome has been the denial of access to the poor, who cannot afford to pay for private care.... For example … user fees have actually succeeded in driving the poor away from health care [while] the promotion of insurance schemes as a means to defray the costs of private health care … is inherently flawed in the African context. Less than 10% of Africa’s labor force is employed in the formal job sector.

… Beyond the issue of affordability, private health care is also inappropriate in responding to Africa’s particular health needs. When infectious diseases constitute the greatest challenge to health in Africa, public health services are essential. Private health care cannot make the necessary interventions at the community level … is less effective at prevention, and is less able to cope with epidemic situations. Successfully responding to the spread of HIV/AIDS and other diseases in Africa requires strong public health care services.

The privatization of health care in Africa has created a two-tier system which reinforces economic and social inequalities…. Despite these devastating consequences, the World Bank and IMF have continued to push for the privatization of public health services.

Furthermore, poverty has contributed to the phenomena of brain drain27

whereby the poor countries educate some of their population to key jobs such as in medical areas and other professions only to find that some rich countries try to attract them away. The prestigious journal, British Medical Journal (BMJ) sums this up in the title of an article: Developed world is robbing African countries of health staff.

(Rebecca Coombes, BMJ, Volume 230, p.923, April 23, 2005.)

Some countries are left with just 500 doctors each with large areas without any health workers of any kind. A shocking one third of practicing doctors in UK are from overseas28, for example, as the BBC reports.

Some of the ideological underpinnings that drive Structural Adjustment have long-continued. For example, the Bretton Woods Project organization summarizes the finding from a recent evaluation of World Bank health work that was damming in its conclusions, while the Bank carries on pushing the same policies:

A World Bank Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) report on almost $18 billion worth of health, nutrition and population work covered projects from 1997 to 2008 across the World Bank Group. It rated 220 projects according to how well they met stated objectives, regardless of how good those objectives were. Highly satisfactory outcomes were almost unheard of, and only about two-thirds of projects had moderately satisfactory outcomes or better. Projects in Africa were

particularly weak, with only 27 per cent achieving satisfactory outcomes. Overall only 29 per cent of freestanding HIV projects had satisfactory outcomes, falling to 18 per cent in Africa.Repeating a consistent criticism of past reports, the IEG found that monitoring and evaluation

remains weakwhileevaluation is almost nonexistent.Only 27 per cent of projects hadsubstantial or highmonitoring and evaluation structures. This has led toirrelevant objectives, inappropriate project designs, unrealistic targets, inability to measure the effectiveness of interventions.

The same Bretton Woods Project article also noted that an earlier review of the implementation of the Bank’s new health sector strategy, which was approved in mid-2007, also had criticism for the Bank finding satisfactory outcomes in only 52 per cent of projects worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africa had the most projects but an abysmal satisfactory rating of 25 per cent

and points to an unwillingness to adapt existing projects based on lessons learned.

Importantly, the article continues, the review admits that Bank management did not commit enough resources to implement the new strategy until more than one year after it had been finalized.

Indeed, as the article notes, the Bank, despite these criticisms (and criticism for many, many years) is pushing for further privatization in health, education and water.

Structural Adjustment has therefore been a major cause of poverty, and as a result, a cause of many health issues around the world.

Large Pharmaceutical Companies—Profit at all costs?

Multinational pharmaceutical companies neglect the diseases of the tropics, not because the science is impossible but because there is, in the cold economics of the drugs companies, no market.

There is, of course, a market in the sense that there is a need: millions of people die from preventable or curable diseases every week. But there is no market in the sense that, unlike Viagra, medicines for leishmaniasis are needed by poor people in poor countries. Pharmaceutical companies judge that they would not get sufficient return on research investment, so why, they ask, should we bother? Their obligation to shareholders, they say, demands that they put the effort into trying to find cures for the diseases of affluence and longevity—heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s. Of the thousands of new compounds drug companies have brought to the market in recent years, fewer than 1% are for tropical diseases.

…

In the corporate headquarters of major drug companies, the public relations posters display the image they like to present: of caring companies that bring benefit to humanity, relieving the suffering of the sick. What they don’t say, is that, so far, their humanity has not extended beyond the limits of the pockets of the sick.

For many years, the large pharmaceutical companies and their lobby groups have come under sharp criticism for intensely lobbying rich country governments to protect their interests around the world through things like enforcement of strict patents laws on medicines, allowing companies to monopolize their products, charging high prices for medicines that people around the world depend on.

For the large companies, they feel their investment into research and development would suffer if other companies then simply copy what they produce. Yet, a lot of the base science and research that the large companies have benefited from has been publicly funded—through university programs, government subsidized research, and other health programs. Privatizing such profits may be acceptable to a certain degree. Certainly, the large pharmaceutical companies have created medicines that have saved millions of people’s lives. However, Jamie Love, an AIDS activist,

denies that the pharmaceuticals even own the rights to the drugs in the first place. He points out that many of the anti-retroviral drugs used to treat HIV and AIDS today stem from the government-funded cancer drug research of the 1980s. The rights to government-created innovations were sold to pharmaceutical companies at low prices … guaranteeing companies like Bristol-Myers Squibb huge returns on investment. Given the public investment in these drugs, Love doesn’t believe drug companies have the moral authority to determine who can or can’t access them. And the fact that thousands of people in Africa continue to die because they can’t afford the drugs adds urgency to his argument.

Some of the plants patented for their medicinal purposes do not even belong to the rich countries where most of the big pharmaceutical companies are based; they come from the developing world, where they have been used for centuries, but patented without their knowledge. Economist and director of the Third World Network, Martin Khor writes,

Just as controversial [as patenting living organisms], or even more so, are patents and patent applications relating to plants that have traditionally been used for medicinal and other purposes (e.g., as an insecticide) by people in developing countries; or patents on medicines for serious ailments. Many medicines are derived from or based on biochemical compounds originating from plants and biodiversity in the tropical and sub-tropical countries. Much of the knowledge of the use of plants for medical purposes resides with indigenous peoples and local communities. Scientists and companies from developed countries have been charged with biopiracy when they appropriate the plants or their compounds from the forests as well as the traditional knowledge of the community healers, since patents are often applied for the materials and the knowledge.

From a purely economic perspective, the idea of patents is to spur innovation, but with pharmaceuticals, it is not just about economics. Dr. Drummond Rennie, from the Journal of the American Medical Association, noted in a television documentary that

Pharmaceuticals, they are a commodity. But they are not just a commodity. There is an ethical side to this because they’re a commodity that you may be forced to take to save your life. And that gives them altogether a deeper significance. But they [big pharmaceutical companies] have to realize that they’re not just pushing pills, they’re pushing life or death. And I believe that they don’t always remember that. Indeed, I believe that they often forget it completely.

However, critics are pointing out that as well as saving lives, they are also taking lives from the poor, especially in the developing world, where, through rich country governments, they have lobbied for policies that will help ensure that their patents are recognized in most countries, thus extending those monopolies on their drugs. Writer and broadcaster, John Madeley, summarizes a number of concerns raised over the years:

[Non-governmental Organizations] allege that the corporations:

- sell products in developing countries that are withdrawn in the West;

- sell their products by persuasive and misleading advertising and promotion;

- cause the poor to divert money away from essential items, such as foodstuffs, to paying for expensive, patented medicines, thereby adding to problems of malnutrition;

- sell products such as appetite stimulants which are totally inappropriate;

- promote antibiotics for relatively trivial illnesses;

- charge more for products in developing countries than they do in the West;

- fail to give instructions on packets in local languages;

- resist measures that would help governments of developing countries to promote generic drugs at low cost;

- use their influence to try to prevent national drug policies;

- give donations of drugs in emergencies which benefit the company rather than the needy;

- use their home government to support their operation with threats if necessary, such as withdrawing aid, if a host government does anything to threaten their interests.

… The methods used by the corporations are highly controversial. Making use of advertising that is inexpensive in comparison to what they pay in industrialized countries, the drug TNCs [Transnational Corporations] use the most persuasive, not to say unethical, methods to persuade the poor to buy their wares. Extravagant claims are made that would be outlawed in the Western countries. A survey, in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that 62 per cent of the pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals

were either grossly misleading or downright inaccurate.

The big pharmaceutical companies have caused enormous uproar in recent years when they have attempted to block poorer countries’ attempts to deal with various health crises. A vivid case is that of South Africa and cheaper generic drugs. The huge pharmaceutical association, PhRMA (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America), and other large companies had intensely lobbied the then US Vice President, Al Gore, in 1999, to threaten South Africa with trade sanctions for trying to develop cheaper, generic drugs to combat AIDS34. They claimed that World Trade Organization (WTO) rules regarding patents and intellectual property were being violated.

In fact, there was no violation. As problematic as the WTO rules have been in this area, there was provision in the rules allowing generic drugs to be created for emergency situations and public, non-commercial use. While public outrage managed to get such a move backed down, the underlying concerns from the big pharmaceutical companies have remained, and in various ways since, they have pressured the United States and other rich, industrialized nations to prevent other countries from doing similar things.

You can understand why the big companies are in fear. When CIPLA, one of India’s leading generics companies, offered a cocktail of anti-retroviral drugs for AIDS at $350 a year, compared to $10,000 from the multinational companies, this sent a shockwave in two ways. Poor countries realized they might have more affordable means to deal with a massive health crisis that afflicts them the most; and the large multinationals saw their monopoly prices severely threatened, and, exposed.

India’s patent laws have allowed the production of cheap generics. CIPLA, for example, offered this low-cost price for their AIDS drug at a loss for itself35, because it said it made profits from other drugs, and this was something that was more than about profit and loss. However, India’s patent law has been under pressure from the rich countries for a long time now. Their patent laws were tightened up in early 2005, to come into line with WTO laws, thus making cheaper alternatives less easy to produce36. This will not only impact India, but also a large majority of the world that looks to India’s generics industry.

Furthermore, as Wired News reported at the end of 2005, India’s new patent laws somewhat ironically now enable pharmaceutical companies to test drugs on India’s poor 37 by using India’s cheaper, but highly skilled workforce to conduct drugs trials there, rather than in industrialized countries, thus saving significantly on the costs. However, as Wired also noted, this introduces a number of issues, such as:

- That although administrations in the industrialized countries, such as the Food and Drug Administration of the US, require that testing shows safety of the products, it is largely up to the country that hosts the trials and tests to ensure that procedures used have been sound and ethical. A developing country such as India does not have the ability to do this as effectively.

- Furthermore, many drugs are being developed for markets in industrialized countries. Yet, using incentives such as $100 for participation (even though patients may not be fully aware of all the issues, which poses other ethical issues) in effect, poor people in other countries are being used for testing drugs on, while the potential benefits would be for people elsewhere. Wired News cited an assitant professor of medical history and bioethics, Srirupa Prasad, who said,

Third World lives are worth much less than the European lives. That is what colonialism was all about.

Brazil too has found itself under pressure from the United States for producing cheaper generics. When its currency devalued in 1999, the case of Brazil also highlighted another issue: the high cost of imported drugs from the big pharmaceutical companies become even more costly as exchange rates fluctuate. Even though the dollar may be relatively weak currently, other rich countries where pharmaceuticals may be purchased from have currently got currencies that are stronger than the dollar. Currencies of course fluctuate. The point is then, that the fluctuation makes it harder for poorer countries to forecast how much the drugs may cost. They, and any other country would be dependent upon price negotiations with the pharmaceutical companies, too.

On April 27, 2003, Britain’s Channel 4 aired a documentary titled Dying for Drugs. Noting that drugs bring billions to big pharmaceutical companies, and hopes to people, they asked, how far would drugs companies go to get their drugs approved and the prices they want?

As the documentary said in their introduction, the implications are alarming and if their power remains unchecked, many more people will soon will be dying for drugs.

In Africa, the documentary showed how one of the world’s biggest drug companies experimented on children without their parents’ knowledge or consent. In Canada, it was revealed how a drug company attempted to silence a leading academic who had doubts about their drug. In South Korea, it followed the attempts of desperately ill patients to make a leading drug company sell them the drugs they need to save their lives at an affordable price. And, in Honduras they showed the brutal consequences of drug companies’ pricing policies whereby to save a 12-year old child dying from AIDS, people had to smuggle drugs from across the border, in Guatemala, breaking the law in the process, just to get the drugs at affordable prices. The child died while the documentary crew filmed the desperate smuggling.

Experts interviewed in the documentary also made some important points of note:

On the controversial high pricing for drugs, the documentary noted, Big pharma generally defends high prices for new drugs … to cover costs for researching and developing new drugs. But in fact, most new drugs launched are just slight variations of existing medicines. So called Me Toos.

Nathan Ford, of Médicins Sans Frontiéres said, At the moment we are getting more and more drugs of less and less use. Me Too drugs; the tenth headache pills; the 15th Viagra. There are currently eight drugs in development at the moment for erectile dysfunction. Do we need 8 more drugs for erectile dysfunction? I don’t think we do. Meanwhile diseases like Malaria, TB that kill 6 million people every a year, are neglected—no new medicines are coming out and we are left treating people with old drugs that increasingly don’t work.

Markets for pharmaceutical companies are not just about finding people to target, but people with money. Dr. Jonathan Quick of the World Health Organization (WHO) added that the majority of the market for some of the tropical diseases is in developing countries but, it’s a market in terms of numbers of people but the purchasing power is not there [and therefore] the normal dynamics of the research and development industry just don’t address those problems.

In another example of how power was used, the documentary noted what happened in Thailand in 1990: the Thai government was making a number of generic drugs. They also wanted to make a generic AIDS drug. However, the U.S. Trade Representative threatened them with export tariffs on wood and jewelry exports, which made up some 30% of Thailand’s total exports. The Thai trade representative was very frightened and they stopped making the generic drugs. The U.S Secretary of Commerce threatened the South Korean Minister of Health in a similar way, but despite those threats, he continued campaigning for cheaper drug prices. He was later sacked. How do companies have such power over entire countries? Jamie Love, also interviewed in this documentary, suggested an answer:

Its because they not only can threaten not to make medicines available, but they can credibly threaten that the U.S. and Europe will impose trade sanctions on those countries and the financial markets will punish them for overriding the patent protection and hurt the rest of the economy. They can actually make the credible threat that if they don’t pay their price for their medicine you won’t be able to sell your products. You won’t be able to have jobs in the manufacturing sector. Your whole economy will suffer.

These, and other examples presented in the documentary were not isolated cases. Hard-fought changes to WTO rules that would have allowed poorer nations easier access to generic drugs was agreed to by virtually every member country in the world, but was resisted by the U.S.—their veto killed the agreement. Side NoteFor more information on this aspect, see the Dying for Drugs link above. See also: Pharmaceutical Corporations and Medical Research39 from this web site; Larry Elliott and Charlotte Denny, US wrecks cheap drugs deal40, The Guardian, December 21, 2002

These complex issues are alive today, as the latest Avian flu concerns confirm. The Third World Network raises the issue again of the role of patents in restricting access to badly needed medicines41, in this case, Tamiflu, recommended by health officials to reduce the severity of this feared flu.

But as J.W. Smith from the Institute for Economic Democracy noted a long time ago, it is of course, a cruel world:

Few have challenged or even recognized the unfair tax upon the unfortunate created by vastly overpriced products and services. There is a consistent pattern; the greater the need, the greater the overcharge. Though the need of those with physical disabilities is great, they have limited power to defend themselves. The first efforts to develop mechanical aids for people with physical problems were undoubtedly undertaken with noble intentions. Typically no profit was involved and much labor and time was donated as generous people tried to help the unfortunate. However, those who knew the value of these aids when monopolized claimed patent rights, and those with disabilities now must pay those monopolists. Witness the hearing aids… Each is only a tiny amplifier, yet costs ten to twenty times as much as a radio, which is hundreds of times larger and much more complicated.

WTO—Patents, Intellectual Property, Emergency Drugs and Developing Countries

Due to what many believe is reasons of bad publicity, many large pharmaceutical companies have given away AIDS and other drugs at cheaper prices and even donated large sums of money to global initiatives. However, less discussed are the many fundamental issues that affect poor countries: access to essential drugs, allowing cheaper alternatives to be more easily made available, patent issues, the rights for poorer countries to pursue these alternatives, and so on.

Many of these issues go to the heart of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the global rules made at this organization to accommodate world trade. However, critics for many years have said that the WTO is overly influenced by the rich countries, who are far more able to wield their economic and political influences to get what is best for them, often at the expense of the developing world. Side NoteSee a collection of articles from this web site’s free trade-related issues43 section for more information.

TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property) is one of the main areas of the WTO agreements. Created in 1994, medicines were included in its patent rules. Some of its rules had come under severe criticism from activists and developing countries. Concerns included that TRIPS allowed monopolization of life-saving drugs for 20 years, risking price increases, and even stifling innovation. Poor countries cannot afford to wait 20 years to enjoy the benefits of important drugs.

Joseph Stiglitz, mentioned earlier, explained in an editorial in the prestigious British Medical Journal that

Intellectual property differs from other property—restricting its use is inefficient as it costs nothing for another person to use it.… Using knowledge to help someone does not prevent that knowledge from helping others. Intellectual property rights, however, enable one person or company to have exclusive control of the use of a particular piece of knowledge, thereby creating monopoly power. Monopolies distort the economy. Restricting the use of medical knowledge not only affects economic efficiency, but also life itself.

We tolerate such restrictions in the belief that they might spur innovation, balancing costs against benefits. But the costs of restrictions can outweigh the benefits. It is hard to see how the patent issued by the US government for the healing properties of turmeric, which had been known for hundreds of years, stimulated research. Had the patent been enforced in India, poor people who wanted to use this compound would have had to pay royalties to the United States.

… The establishment of the World Trade Organization … imposed US style intellectual property rights around the world. These rights were intended to reduce access to generic medicines and they succeeded. As generic medicines cost a fraction of their brand name counterparts, billions could no longer afford the drugs they needed.

…

Developing countries paid a high price for this agreement. But what have they received in return? Drug companies spend more on advertising and marketing than on research, more on research on lifestyle drugs than on life saving drugs, and almost nothing on diseases that affect developing countries only. This is not surprising. Poor people cannot afford drugs, and drug companies make investments that yield the highest returns. The chief executive of Novartis, a drug company with a history of social responsibility, said

We have no model which would [meet] the need for new drugs in a sustainable way … You can’t expect for-profit organizations to do this on a large scale.

Developing countries had to enforce the TRIPS rules by 2005, but the Least Developed Countries (LDCs)—32 of them in the WTO—had until 2006. (In the 2005 WTO meetings in Hong Kong45, LDCs requested a 15-year extension for administrative, economic, and financial reasons. This was reduced to a 7½–year extension with conditions attached46 (for example, any changes in the meanwhile must not be less consistent with the provisions of the TRIPS agreement.)

During the WTO meeting in Doha, Qatar, 200147, the overall outcome was not seen as favorable for the poor. However, one area where there was some success was in health issues. Slightly strengthened WTO TRIPS rules meant governments that could not afford branded drugs would be able to take measures to protect health a bit more easily by creating cheaper generics themselves, through compulsory licensing.

WTO patent rules still allow 20 years of exclusive rights to make the drugs. Hence, the price is set by the company, leaving governments and patients little room to negotiate—unless a government threatens to overturn the patent with a compulsory license.

Such a mechanism authorizes a producer other than the patent holder to produce the product though the patent-holder does get some royalty to recognize their contribution.

Parallel importing is another potentially powerful mechanism available to poor countries. Effectively, it allows a nation to shop around for the best price for the same drug, which may be sold in many countries at different prices.

Compulsory licensing and parallel importing (in particular, parallel importing of generic drugs) are very effective tools to get prices down for developing countries. For example, the above-mentioned documentary noted that a drug in question had been offered in Brazil at dramatically reduced cost by Novartis themselves because of the threat that generic versions would have posed. (In the Europe Union (EU), parallel importing has been practiced for a while, though it is only on brand drugs and only amongst EU member states, so the benefits to patients of reduced prices appear more questionable. Side NoteFor more information on this, see for example: EU pharmaceutical parallel trade—benefits to patients?48 from the London School of Economics, January 27, 2004; European Union should liberalize drug market, EU judge says49, from Bloomberg, April 18, 2005.)

However, compulsory licensing laws in TRIPS imply that generics are only to be used for domestic purposes, not for export, and so parallel importing—which has been strongly resisted by the US and the pharmaceutical multinationals—was not part of the 2001 agreement. In reality, this means that given most poor countries do not have a sophisticated domestic pharmaceutical industry and thus would not have the ability to make their own generics, they would likely have to purchase the more expensive branded drugs.

At the next major WTO meeting, in Cancun, Mexico in September 2003, the developing countries managed to get another small win. But parallel importing may still prove difficult:

Developing countries successfully stopped the US and the pharmaceutical lobby from excluding many important diseases of the third world from the deal, which is an important achievement. However no matter how desperate the health need, a poor country without the capacity to produce a needed drug—which is virtually all of them—will have to ask another government to suspend the relevant patent and license a local company to produce and export it.

Few countries, if any, will be prepared to help other countries in this way, as it would provoke retaliation by the US, which fiercely defends the commercial interests of the drug companies. What is more the agreement is wrapped in so much red tape and uncertainty that in practice it will be very difficult to use.

The bottom line is that many poor countries will still have to pay the high price for patented medicines or most probably, doing without. The World Trade Organization has failed to live up to the Doha pledge to put people’s health before profits.

This waiver

as it was in 2003, will now become a permanent amendment to the TRIPS agreement. While praised by some richer countries as meeting poorer countries concerns, poorer countries and NGOs criticized it codifying a difficult-to-work waiver, which no one has used yet and thus is unproven51.

In addition, as noted further above however, the US has sought to undermine the agreement made at Doha. Oxfam, a prominent NGO, has been highly critical of the practices of big pharmaceutical companies, arguing that, The U.S. Trade Representative is pursuing standards of patent protection which go far beyond WTO patent rules, and it is doing so regardless of the devastating impact that this could have on … developing countries.

Oxfam also believes the US is pursuing this pro-patent agenda on behalf of its powerful pharmaceutical lobby, PhRMA. The industry has an interest in strong patent protections, which limit generic competition and therefore protect its market share and profits.

Furthermore,

The cheapest generic versions of new patented drugs are being blocked from developing-country markets by U.S. trade policies on intellectual property, at the urging of the drug companies that benefit from the monopoly position that patents confer.

During the two years since Doha, the U.S. has contravened the goal of the Declaration—‘access to medicines for all’—by pressuring developing countries to implement ‘TRIPS-plus measures’: patent laws which go beyond TRIPS obligations and do not take advantage of its public-health safeguards. The USA does this in a number of ways. It provides biased technical assistance in countries such as Uganda and Nigeria, which benefits its own industry by increasing drug prices and limiting the availability of generics, but reducing access. It uses bilateral and regional free trade agreements to ratchet up patent protection in developing countries. It has recently concluded free trade agreements with Chile and Singapore and is using the high intellectual property standards in the latter as a model for negotiations on the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas … and with Central American, Southern African, and other countries. And lastly, the U.S. bullies countries into increasing patent protection by threatening them with trade sanctions under section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974; nearly all those targeted are developing countries, including countries in compliance with their WTO obligations. The Costa Rican Pharmaceutical Industry estimates that the implementation of such TRIPS-plus patent rules would mean an increase in the cost of medicines of up to 800 per cent, because these rules would seriously restrict competition from generics.

Martin Khor reported for the Third World Network on a global AIDS conference in Bangkok, July, 2004 and also commented on the negative impacts of the growing number of bilateral agreements signed with the US53 that Oxfam alluded to. These agreements, Khor wrote, are creating new barriers to access to medicines, as they forbid the developing countries from policies (which the WTO allows) that promote generic medicines.

To add to the sour French-US political relations, There was a diplomatic uproar when the French President Jacques Chirac accused the US of blackmailing developing countries to give up measures to obtain life-saving drugs through these bilateral trade deals.

A worrying development, seen at the G8 2007 summit54, though hardly reported in the mainstream media, is the attempt to shift discussion of intellectual property rights away from the WTO, to the OECD55. While there are many issues and concerns already with the WTO process, it is at least a somewhat global forum. The OECD is like the rich countries club

and so this tactic of course is political. If it succeeds, it will further limit global dialogue, undermining any notion of a global level of participation and democracy which is already poor.

Global Health Initiatives

Since around 2000, a number of global initiatives have been set up to deal with various global health crises. To their credit, the big pharmaceutical companies have been actively involved in them, too.

Mega-rich individuals, such as Bill Gates, have also shown incredible charity by donating hundreds of millions of dollars to these initiatives. Some of the donations from people like Bill Gates are not without their criticisms for other motives, however. Side NoteSee for example, Gates gives $100m to fight HIV, $421m to fight Linux56, by Thomas C. Greene, The Register (UK), November 11, 2002; Bill Gates: Killing Africans for Profit and PR57, by Greg Palast July 14, 2003. But more fundamentally, as the magazine Himal South Asia notes,

Private charity is an act of privilege, it can never be a viable alternative to State obligations,said Dr James Obrinski, of the organization Médicins Sans Frontiéres, in Dhaka recently at the People’s Health Assembly…. In a nutshell, industry and private donations are feel-good, short-term interventions and no substitute for the vastly larger, and essentially political, task of bringing health care to more than a billion poor people.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria was created at the urging of UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, in 2001. It was supposed to be the largest fund set up to tackle these global health issues. However, it has suffered from poor funding, slow distribution, and other political obstacles from some of the richest countries such as the US that would prefer to have their own initiatives so they have more control over where the money goes (the Global Fund is supposed to be a fund where countries donate without any strings attached. The US, as the international HIV and AIDS charity AVERT criticizes, prefers to go via its own PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief). This allows the US to avoid supporting countries perceived to be hostile, or those who may support programs it currently does not like—such as abortion and condom use, or use of generic drugs. For a good overview about the challenges and obstacles for the Global Fund, see The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria59 by AVERT, September, 2005).

As Oxfam and other organizations have charged, the large pharmaceutical companies are using corporate philanthropy to push their products at prices that would still be higher than generics, which poorer countries would be able to afford:

Several major pharmaceutical corporations are supporting international initiatives either by donating drugs or by subsidizing drugs provision, often receiving generous tax benefits in return. There are longstanding initiatives in place for controlling malaria, tuberculosis, and river blindness.

Pharmaceutical companies cite such agreements as evidence that strict patent protection under the WTO is compatible with socially responsible marketing. Reality is more prosaic. The main problem with these initiatives is that drugs are often made available in limited quantities, and at prices which compare unfavorably with those for generic-equivalent products.

During 2000, these initiatives were supplemented by an agreement between UNAIDS and five pharmaceutical companies … to improve access to treatment for HIV-positive people in developing countries [and] provide anti-retroviral products at significant discounts as part of a national AIDS plan.

Nevertheless, it has been slow to implement … and many African governments continue to argue that the waiving of patent rights on life-saving drugs would be a far more effective way of bringing down prices.

In effect … Commercial self-interest and corporate philanthropy are pulling in different directions. [Emphasis is original]

Increasing commodification and commercialization of healthcare

As noted earlier, structural adjustment, increasing influence of multi-national corporations and ideology are contributing to a change in health care provision, away from the principle of universal health care and rights, to individual management and privilege. The World Health Organization is worth quoting at length regarding this important shift:

However, broad global currents of macroeconomic policy change have strongly influenced health-sector reforms in recent decades in ways that can undermine such benefits. These reforms include encouragement of user fees, performance-related pay, separation of the provider and purchaser functions, determination of a package that privileges cost-effective medical interventions at the expense of priority interventions to address social determinants, and a stronger role for private sector agents. These have been driven strongly by a combination of international agencies, commercial actors, and medical groups whose power they enhance. The result has been on the one hand an increasing commercialization of health care, and on the other, a medical and technical focus in analysis and action that have undermined the development of comprehensive primary health-care systems that could address the inequity in social determinants of health.

Opening the health sector to trade, reform processes have split purchasers and providers and have seen increasing segmentation and fragmentation in health-care systems. Higher private sector spending (relative to all health expenditure) is associated with worse health-adjusted life expectancy, while higher public and social insurance spending on health (relative to GDP) is associated with better health-adjusted life expectancy. Moreover, public spending on health is significantly more strongly associated with lower under-5 mortality levels among the poor compared to the rich. The Commission considers health care a common good, not a market commodity.

This ideological shift seems to be coming at a cost, too:

Underlying these reforms is a shift from commitment to universal coverage to an emphasis on the individual management of risk. Rather than acting protectively, health care under such reforms can actively exclude and impoverish. Upwards of 100 million people are pushed into poverty yearly through the catastrophic household health costs that result from payments for access to services.

Runaway commodification of health and commercialization of health care are linked to increasing medicalization of human and societal conditions, and the stark and growing divide of over- and under-consumption of health-care services between the rich and the poor worldwide. The sustainability of health-care systems is a concern for countries at all levels of socioeconomic development. Acknowledging the problem of sustainability in the context of a call for equitable health care is a vital first step in more rational policy-making, as is strengthening public participation in the design and delivery of health-care systems. The inverse care law, in which the poor consistently gain less from health services than the better off, is visible in every country across the globe. A social determinants of health approach to health-care systems offers an alternative – one that unlocks the opportunities for greater efficiency and equity.

It is not necessarily the case that the private sector must be shunned. The report itself notes the benefits that the private sector can bring to health issues, but it needs to be appropriate:

Markets bring health benefits in the form of new technologies, goods and services, and improved standard of living. But the marketplace can also generate negative conditions for health.… Health is not a tradable commodity. It is a matter of rights and a public sector duty. As such, resources for health must be equitable and universal.… experience shows that commercialization of vital social goods such as education and health care produces health inequity.

… this does not imply a relegation of the importance of private sector activities. It does, though, imply the need for recognition of potentially adverse impacts, and the need for responsibility in regulation with regard to those impacts. Alongside controlling undesirable effects on health and health equity, the vitality of the private sector has much to offer that could enhance health and well- being. Actions include:

- Strengthening accountability: Recognize and respond accountably to international agreements, standards, and codes of employment practice … and ensure private sector activities and services (such as production and patenting of life-saving medicines, provision of health insurance schemes) contribute to and do not undermine health equity.

- Investing in research: Commit to research and development in treatment for neglected diseases and diseases of poverty, and share knowledge in areas (such as pharmaceuticals patents) with life-saving potential.

Issues of medical drugs, how they are researched, developed, patented, made available (or not), priced, etc are all important issues, as also discussed earlier, but research shows how a significant proportion of the global burden of both communicable and non-communicable disease could be reduced through improved preventive action.

(p.97).

This is also important from another perspective: a lot of public attention is drawn to large foundations and mega donations to make drugs more affordable or accessible, or other such treatments available. While these are important (and also come with their own criticisms as mentioned earlier), a deeper issue is that this has often driven much needed resources away from preventative healthcare to treatment, when investment in preventative care could be a lot more effective.

Inter Press Service reported on this aspect in response to George Bush’s tripling of U.S. spending over the next five years to fight HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis in poor countries, to 48 billion dollars, and is quoted a few times here:

Ruth White, an associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Seattle University who runs an aid organization, says that a narrow focus on disease has drawbacks.

It’s dangerous because it sucks up resources that could be spread around to have more general health impact instead of focusing efforts on people with one disease and ignoring people with others,she said.

Basic nutrition can help provide immunity support that can prevent or ameliorate malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis. When people have poor nutrition and are generally unhealthy they are more susceptible to these illnesses,White said.

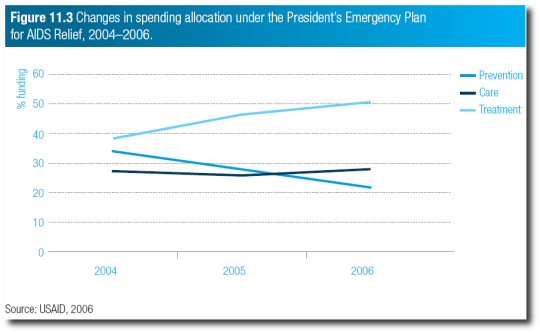

The above-mentioned WHO report also noted the same trend, and pointed to the US PEPFAR spending allocations as a good example of this:

Carter also noted a Los Angeles Times article that further highlighted how problematic this narrow focus can be, focusing on the massive Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation:

According to the Los Angeles Times, the strict disease focus carried out by the Gates foundation has created some problematic results.

The Times found that the high level of grants provided by the Gates Foundation to fight high-profile disease, notably HIV/AIDS, has led to recipients increasing their demands for specially trained clinicians, resulting in a diverting of staff from basic medical care. Such shortages have led to increased neglect of common medical conditions.

According to the article, such focus has shortchanged basic needs like nutrition and transportation. In many instances, patients actually vomit up their free AIDS medication due to malnutrition, and others lack money to travel to clinics providing such life-saving services.

The article continues, noting that emphasis on diseases such as AIDS is prominent because it also affects developed nations, and malaria and TB are spreading. Yet, sometimes the most effective ways to address this can be, for example, to improve water sanitation rather just a focus on drugs. However, water infrastructure can also be a costly project. This issue of focusing on malaria, AIDS and tuberculosis is important, but the donor community must consider how funding is allocated, said Kirk Anderson of Water First International.

We often hear that education for affected segments of society is critical for effective health and other problems to be resolved. Kirk also added an interesting twist to tackling health issues by noting that education on how to be good philanthropists is also needed.

Changing Dynamics in Global Health Issues and Priorities

Increasingly, the world is becoming urbanized. Estimates suggest about half of humanity now lives in the cities. As the earlier-mentioned WHO report on the social determinants to health notes, of the approximately 3 billion people living in cities, just under 1 billion live in slums.

This is changing the dynamics of global health problems:

Infectious diseases and undernutrition will continue in particular regions and groups around the world. However, urbanization itself is re shaping population health problems, particularly among the urban poor, towards non-communicable diseases and injuries, alcohol- and substance-abuse, and impact from ecological disaster.

Obesity is one of the most challenging health concerns to have arisen in the past couple of decades. It is a pressing problem, particularly among socially disadvantaged groups in many cities throughout the world. The shift in population levels of weight towards obesity is related to the ‘nutrition transition’ – the increasing consumption of fats, sweeteners, energy-dense foods, and highly processed foods. This, together with marked reductions in energy expenditure, is believed to have contributed to the global obesity epidemic. The nutrition transition tends to begin in cities. This is due to a variety of factors including the greater availability, accessibility, and acceptability of bulk purchases, convenience foods, and ‘supersized’ portions.

(See also this site’s section on obesity67 for more information on that issue.)

The above 2008 report mentioned noncommunicable diseases being on the increase. In a report a couple of years later, the WHO reiterates its concerns about the impact of NCDs, which are the leading cause of deaths worldwide. It laments that attempts to come up with effective health policies have often failed for a variety of reasons:

Despite abundant evidence, some policy-makers still fail to regard NCDs as a global or national health priority. Incomplete understanding and persistent misconceptions continue to impede action. Although the majority of NCD-related deaths, particularly premature deaths, occur in low- and middle-income countries, a perception persists that NCDs afflict mainly the wealthy.

Other barriers include the point of view of NCDs as problems solely resulting from harmful individual behaviours and lifestyle choices, often linked to victim ‘blaming’.

The influence of socioeconomic circumstances on risk and vulnerability to NCDs and the impact of health-damaging policies are not always fully understood; they are often underestimated by some policy-makers, especially in non-health sectors, who may not fully appreciate the essential influence of public policies related to tobacco, nutrition, physical inactivity and the harmful use of alcohol on reducing behaviours and risk factors that lead to NCDs.

Overcoming such misconceptions and viewpoints involves changing the way policy-makers perceive NCDs and their risk factors, and how they then act. Concrete and sustained action is essential to prevent exposure to NCD risk factors, address social determinants of disease and strengthen health systems so that they provide appropriate and timely treatment and care for those with established disease.

Impact on development)

The above report also notes further the negative impact of globalization:

The rapidly growing burden of NCDs in low- and middle-income countries is accelerated by the negative effects of globalization, rapid unplanned urbanization and increasingly sedentary lives. People in developing countries are increasingly eating foods with higher levels of total energy and are being targeted by marketing for tobacco, alcohol and junk food, while availability of these products increases. Overwhelmed by the speed of growth, many governments are not keeping pace with ever-expanding needs for policies, legislation, services and infrastructure that could help protect their citizens from NCDs.

As noted above, physical activity is also affected by urban surroundings, which an earlier WHO report detailed further:

Physical activity is strongly influenced by the design of cities through the density of residences, the mix of land uses, the degree to which streets are connected and the ability to walk from place to place, and the provision of and access to local public facilities and spaces for recreation and play. Each of these plus the increasing reliance on cars is an important influence on shifts towards physical inactivity in high- and middle-income countries

In crowded places, environmental factors such as pollution also become a factor and interact with issues such as physical inactivity (e.g. increasing use of cars contributes to more air pollution, greenhouse gases and less physical activity.

The WHO also notes that with increasing urbanization comes increasing violence and crime. In addition, the effects of depression and social exclusion can become more profound. About 14% of the global burden of disease has been attributed to neuropsychiatric disorders, mostly due to depression and other common mental disorders, alcohol- and substance-use disorders, and psychoses. The burden of major depression is expected to rise to be the second leading cause of loss of disability-adjusted life years in 2030 and will pose a major urban health challenge.

(pp.62-63)

Even the demands of increasing globalization has a health impact. For example, more people are working in informal sectors or part time. Increasingly influential transnational corporations are pushing for more labor flexibility to stay competitive. Reduced real income as people work longer hours and under more stress also means more health issues. Furthermore, some 487 million people (out of the 3 billion labor force) do not earn enough to lift themselves and their families out of poverty (p.73).

Further, globally, it is estimated that there are about 28 million victims of slavery, and 5.7 million children are in bonded labor (p.74). And more than 200 million children globally aged 5-17 years are economically active.

When employment is coercive, exploitative, or accompanied by harsh/unfair conditions, established health and safety standards are less likely to be applied. If populations are becoming increasingly flexible while real incomes are reducing, these can all have a knock-on effect on health issues.

Summary

Poverty exacerbates health issues. Under conditions of poverty, entities such as large pharmaceutical companies can wield even more power and influence over poorer countries. Some major reasons for unnecessary deaths around the world are therefore due to human decisions and politics, not just natural outcomes. Well-intentioned companies, organizations and global action show that humanity and compassion still exists, but tackling systemic problems is paramount for effective, universal health care that all are entitled to.

Addressing health problems goes beyond just medical treatments and policies; it goes to the heart of social, economic and political policies that not only provide for healthier lives, but a more productive and meaningful one that can benefit other areas of society.

(Image credit: health shield courtesy of DevCom71)

0 articles on “Global Health Overview” and 1 related issue:

Health Issues

Around the world, large numbers of people suffer unnecessarily and die from often easily preventable illnesses and conditions. For example, an estimated 1 billion people lack access to health care systems while millions die each year from diseases such as malaria, Tuberculosis and AIDS.

Around the world, large numbers of people suffer unnecessarily and die from often easily preventable illnesses and conditions. For example, an estimated 1 billion people lack access to health care systems while millions die each year from diseases such as malaria, Tuberculosis and AIDS.

While health service provision is a desire for most people, nations struggle to find sufficient funds as they face high drug prices (sometimes with drug companies challenging countries—especially poor ones—that may legally try to create cheaper generic ones when faced with urgent health issues) while changing lifestyles are contributing to deteriorating health.

Read “Health Issues” to learn more.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues