State-Owned Companies Are Key to Climate Success in Developing Countries, but Are Often Overlooked in the International Dialogue

WASHINGTON, Sep 16 (IPS) - Later this month, government officials and climate stakeholders will once again converge on New York City (this time virtually) for Climate Week and the United Nations meetings. And while there will be much discussion about the important role that actors such as private businesses, civil society and cities will need to play in the climate change effort, there will once again be relatively little discussion about one key cohort: government-owned companies.

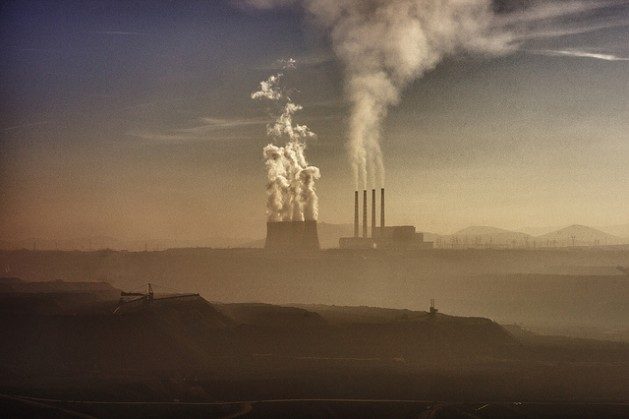

Although these companies are not prominent in many of the OECD countries that to date have dominated the climate change dialogue, they are major drivers of greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in emerging economies and other developing countries. To meet the global warming goals of the Paris Agreement, these government-owned companies must receive greater attention in climate discussions.

Globally, government-owned companies (also referred to as state-owned enterprises or "SOEs") annually emit over 6.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide-equivalent in energy sector greenhouse gases. This is more than all the emissions of the United States, or of the combined total of the European Union and Japan. In China, the world's highest emitting country, its state companies are responsible for over half of national energy emissions.

SOEs are often controversial, generally viewed as inefficient by the development community that has sought to reform or even eliminate them -- but when it comes to climate, these companies are and will remain major actors in energy and other sectors that are central to the low-carbon effort.

SOEs are important players in the power sector that is responsible for 40% of global energy emissions. These companies are particularly weighty in many of the developing world's power systems, notably in coal generation that is key to reducing emissions.

Whether it is the larger emerging economies of Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico or South Africa or many smaller poorer developing companies (or even some advanced economies, such as France), government-owned companies are the lead players in electricity.

Oil and gas companies generate 15% of total energy GHG emissions through their own production and other operations, and provide the petroleum products burnt by others. While many of the best-known companies are private sector ones, such as ExxonMobil, Shell and BP, most of the world's oil reserves are owned by national oil companies and their governments, and the world's most profitable company in 2018 was state-owned Saudi Aramco.

Governments also own some of the largest coal mining companies in the world. These oil, gas and coal producers present a particular challenge for the low-carbon transition because their corporate purpose is intertwined with fossil fuel production.

SOEs are also very present in heavy industry (such as steel, cement and chemicals) which uses large amounts of fossil fuels and produces correspondingly high amounts of emissions. Many of the world's urban transit systems are also major consumers of energy: from Latin America to Asia, and even in New York City and other major U.S. cities, the buses and other transport that people ride and which produce emissions are owned by government entities (often cities and regional organizations).

The importance of SOEs to the climate effort is not only about emissions, it is also about the low-carbon alternatives they provide. Governments own over half of the world's zero-carbon utility-scale electricity generation.

Similarly, state-owned cement and steel companies in India and elsewhere are developing energy efficiency and other low-carbon technologies to reduce their emissions, and many urban transit systems are reducing their carbon footprints by acquiring electric buses and making energy efficiency investments.

Moreover, the state plays a major role in funding both high- and low-carbon projects. While much media attention is given to announcements by leading private international banks, state-owned banks are amongst the world's largest financial institutions.

In many emerging economies and developing countries throughout Asia, Latin America and Africa, state-owned development and commercial banks are major sources of funding for energy projects, including smaller-scale low-carbon investments by the private sector.

One specific and often overlooked class of state-owned banks that plays an important role in the energy transition is multilateral financial institutions, such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. These organizations are not generally viewed as SOEs, but they are -- it is merely that they are owned by several national governments simultaneously.

And, finally, SOEs play a critical role in adaptation and resilience. Many of the world's electricity transmission and distribution systems are owned and operated by government entities. State Grid Corporation of China is the largest with over 1 billion customers.

Even as countries have moved to liberalize their power markets to promote private sector participation in generation, the electricity grid often remains under state control (e.g., in the form of an independent system operator).

The government also plays a central ownership role in many natural gas and other energy networks. When hurricanes hit or rivers flood roads and towns or high winds knock down transmission lines, it is often up to government entities to get the energy system running again. As the prospect for extreme weather events increases, SOEs will face a growing challenge to deliver resilient energy systems.

From emissions to low-carbon alternatives, from power to oil and gas and coal, from heavy industry to transport, from financing to resilience, state-owned enterprises are critical actors in the climate change effort. They are also in many ways a class unto themselves, albeit a diverse one.

Their government ownership distinguishes them from the private sector actors that have generally been targeted in the conceptualization of climate policy tools (such as carbon taxes and other liberalized market-oriented instruments). Given the importance of state-owned enterprises in driving emissions, more thought and attention need to be paid to developing SOE-tailored tools to effectively engage them in climate action.

Philippe Benoit is Managing Director for Global Infrastructure Advisory Services 2050 and has written extensively on the issue of state-owned enterprises and climate. He was previously the Head of the Energy Environment Division at the International Energy Agency and Energy Sector Manager for Latin America at the World Bank.

© Inter Press Service (2020) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Where next?

Browse related news topics:

Read the latest news stories:

- UN Chief's Ramadan Solidarity Visit Revives Rohingya Refugees Hope Saturday, March 15, 2025

- UN chief affirms solidarity with Bangladesh amid political transition Saturday, March 15, 2025

- ‘Time for bold moves’: UN urges inclusive transition as Syria marks 14 years of conflict Saturday, March 15, 2025

- ‘Is this just a long, beautiful dream?’: Syrian filmmaker Waad Al-Kateab on her country’s future Saturday, March 15, 2025

- Trump, Democracy and the U.S. Constitution Friday, March 14, 2025

- Is UN in Danger of Losing its Battle for Gender Equality? Friday, March 14, 2025

- ‘Without us, there is no future’: Youth take over UN Women’s Commission Friday, March 14, 2025

- No food deliveries to Gaza as border closures continue Friday, March 14, 2025

- World News in Brief: Fresh fighting in eastern DR Congo, global trade update, elections in CAR, Pakistan train hijack Friday, March 14, 2025

- Reject bigotry and discrimination, UN chief says, urging everyone to combat Islamophobia Friday, March 14, 2025