AIDS around the world

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/219/aids-around-the-world.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

At the World Bank, an internal study found what South African economist Alan Whiteside ridiculed as a

silver liningin the plague.

If the only effect of the AIDS epidemic were to reduce the population growth rate, it would increase the growth rate of per capita income in any plausible economic model,said the June 1992 report by the bank’s population and human resources department. Exactly that had happened in the 14th century, the report said, with the bubonic plague. The report did not conclude that AIDS would be a benefit to Africa, even in strictly economic terms, but it hardly marked a clarion call to action.

Only the World Bank would put that on paper,Whiteside said.

AIDS and HIV has reached epidemic proportions in many developing countries. It is serious enough for the United States to consider it a threat to its national security and in some nations has had a large impact on mortality rates and the economy.

On this page:

Scale of the AIDS Epidemic

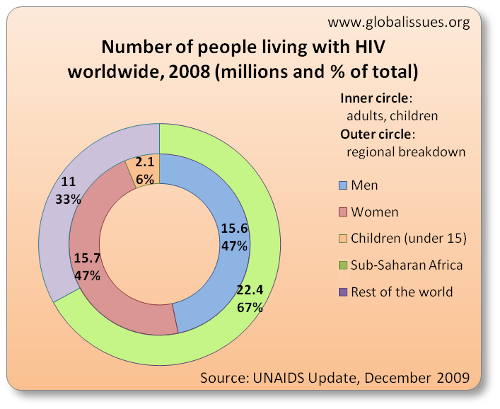

UNAIDS estimated that for 2008 worldwide, there were:

- 33.4 million living with HIV

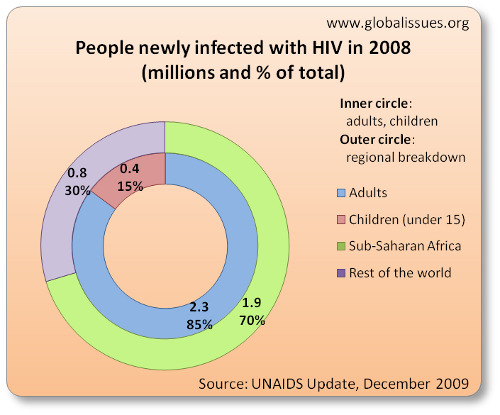

- 2.7 million new infections of HIV

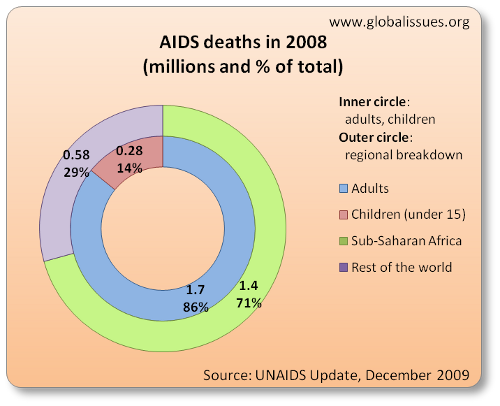

- 2 million deaths from AIDS

Approximately 7 out of 10 deaths for 2008 were in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region that also has over two-thirds of adult HIV cases and over 90% of new HIV infections amongst children. Breaking that down further:

In some regards, the numbers show increases, but at the same time, recent years have shown some attempts to tackle the problem as being successful:

While the number of those living with HIV has increased, a part of this is also because some successful treatment has meant more people have survived. The above-mentioned report also provides estimates on how many lives have been saved by certain drugs, where available.

Nonetheless, some areas are still seeing problems, and treatment could be potentially more widespread, and even more lives could be saved than have already been.

A Disease Largely of Poverty

For a long time now, AIDS has been understood to be a disease largely of poverty:

Among all low- and middle-income countries, HIV prevalence is strongly correlated with falling protein consumption, falling calorie consumption, unequal distribution of national income and, to a lesser extent, labor migration…. Poverty not only creates the biological conditions for greater susceptibility to infectious diseases, it also limits the options for treating disease.

For wealthier people in industrialized countries, there is a better chance to afford the very expensive treatment that is available.

However, for the vast majority of HIV and AIDS sufferers in the developing countries, such treatment is not available. The spread and epidemic of AIDS is also largely a result of poverty and debt conditions, some of which has been brought on upon by the economic policies of western backed institutions:

Although there are numerous factors in the spread of HIV/AIDS, it is largely recognised as a disease of poverty, hitting hardest where people are marginalised and suffering economic hardship. IMF designed Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), adopted by debtor countries as a condition of debt relief, are hurting, not working. By pushing poor people even deeper into poverty, SAPs may be increasing their vulnerability to HIV infection, and reinforcing conditions where the scourge of HIV/AIDS can flourish.

(For more about the causes of poverty, debt and the various trade and economic conditions that have fostered such an environment, visit this web site’s section on Trade, Economy, & Related Issues.)

Corporate reaction to the AIDS/HIV epidemic

Profiting from death— … the AIDS epidemic has brought billions of dollars in profits to the world’s pharmaceutical companies—the newest combination drug therapies can cost up to 20,000 US dollars per person per year. There have been strong calls for companies to cut these prices, and worldwide condemnation of drugs giant Glaxo-Wellcome for raising the price of its market leader AZT as well as holding back access to new drugs. Until people’s needs are put before corporate profits, there will be one AIDS epidemic for the rich and another for the poor.

For information about the shocking corporate reaction to some developing nations’ attempts to try and provide drugs for their populations, go to this site’s section on Pharmaceutical Corporations and AIDS.

You can also visit this web site’s section for information about corporations and medical research in general.

Rich only seem to care when it affects them?

For many years, wealthier countries were criticized for not acting on this issue sooner. (It seemed it only became a major international concern for wealthy countries around the time the US announced AIDS/HIV as a potential national security issue.) Some have also argued that once wealthy nations realized they had escaped the worst, their interest diminished somewhat:

James Sherry, director of program development for the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, or UNAIDS, finds it difficult to speak of the wasted lives without bitterness.

I can’t think of the coming of any event which was more heralded to less effect,he said.… the people who are dying from AIDS don’t matter in this world.…

for a decade, the world knew the dimensions of the coming catastrophe and the means available to slow it. Estimates ranged widely, but the World Health Organization in 1990 and 1991 projected a caseload, and eventual death toll, in the tens of millions by 2000. Individually and collectively, most of those with power decided not to act.

How and why they made their choices is … a story of authentic doubts for a time because the disease concealed itself in years of latency and layers of social taboo. It is also a story, by turns, of willful ignorance and paralysis in the face of growing proof. Its direction is marked by wealthy nations’ loss of interest once they understood they had escaped the worst, by racial undercurrents, and by poisonous turf battles among the multinational bodies charged with marshaling a response. At nearly every level, the process featured what some participants now see as shameful

demand management: reluctance to take available steps for fear of prompting still greater claims on time and money.

The first reaction is,said William H. Foege, who directed the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) until 1983, speaking of 1990s estimates that it would take as much as $3 billion a year to fund global AIDS prevention.That’s impossible. We could never spend those kinds of resources,Then you have to remember, that’s how much we spend on health care in the United States every day. It makes you wonder what’s wrong with us, and how will history judge our response.

Also see this site’s section on AIDS in Africa for more on this aspect.

In more recent years, public pressure has brought about a change in attitude amongst rich countries. From huge music concerts to corporate programs that encourage purchasing of goods and services whereby some proceeds will go to funding the Global Fund to fight AIDS, awareness and action has been increasing. It is not without its problems though, as issues such as cost and access to medicines, sufficient funding, etc. are still major problems.

Education for Prevention is Key

While there are many criticisms of external parties, as mentioned above, on top of that, there are still issues within affected societies to over come. In many nations, corruption is a hindrance. There is still the stigmatization in many places, of a disease such as AIDS. There are various cultural issues and barriers to overcome to help spread the awareness and provide treatments and, equally important, introduce preventative measures.

In some countries, there are social taboos, denial and even old patriarchal beliefs that prevent open discussions.

Furthermore, as mentioned above, many of the poor nations are also affected by the IMF and World Bank structural adjustment policies, which force nations to cut back on health, education and other services—the very things that are vital here.

And while pharmaceutical companies’ research on cures—and the way that they are doing it—is raising appropriate criticisms and concerns, this attention also diverts the much needed emphasis on prevention as summarized by the following:

What might be overlooked, however, as life-sustaining drugs become available, is the fact that prevention is still by far the more compassionate and more cost-effective answer. Prevention does not replace treatment, but it does reduce the number of people whose lives will depend on expensive drugs with significant side effects.

…

Attending to broader health concerns is not as expensive, or as hopeless, as it might seem. There are also serious weaknesses in a prevention plan that relies exclusively on provision of condoms, even with health education. It does not address women’s lack of power in sexual relationships, nor the irrelevance of condoms to most people after a few beers. Strengthening immune systems will help to protect people from some of the consequences of unsafe sex and from other infectious diseases as well. What it will take to prevent HIV transmission and to treat people with HIV/AIDS is no less, but no more, than what has been needed all along in sub-Saharan Africa and other poor regions. It would have been cheaper to provide the infrastructure, the nutrition, the education and the medicines before HIV/AIDS, but it is still a bargain calculated in both compassionate and cost-effective terms.

There is also the phenomenon of brain drain

whereby the poor countries educate some of their population to key jobs such as medical areas and other professions only to find that some rich countries try to attract them away. The prestigious British Medical Journal (BMJ) sums this up in the title of an article: Developed world is robbing African countries of health staff

(Rebecca Coombes, BMJ, Volume 230, p.923, April 23, 2005.) Some countries are left with just 500 doctors each with large areas without any health workers of any kind. One third of practicing doctors in UK are from overseas as the BBC notes.

Funding for tackling global AIDS problem is also needed

In June 2001, a global AIDS fund was finally set up.

Rather than tackling specific issues, the Fund was set up to be the largest funding mechanism for global health issues and programs, signifying a dramatic break from historical methods of aid allocation

as Peris Jones noted in Of gifts and return gifts

, From Disaster to Development? HIV and AIDS in Southern Africa, (Interfund, December 2004), pp.171-172 . The Fund is not an implementer and does not impose conditionalities upon recipients,

which is a major criticism for many aid disbursements. Instead, its innovation lies in the apparent attempts to promote local ownership and planning. Countries are asked to identify needs and come up with solutions, which the Fund will finance.

However, there have been criticisms about the funds that have been contributed by the wealthiest nations. For example, the two largest donors—U.S. and U.K—gave 200 million dollars each in the first year. While it was welcomed at the time, it was also criticized as not enough. $200 million is roughly what Sub-Saharan Africa spends each week on debt repayment. (You can also listen to this Democracy Now! radio show interview on the topic, from June 28, 2001.)

Christian Aid echos those concerns, but also adds that more fundamentally, the AIDS fund ignores the root causes:

In June the Global AIDS and Health Fund was launched with great fanfare. The fund should have been up and running by now, but six months on, the $10bn target proposed by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan stands at just $1.5bn. Administrative structures are not in place and no money has been disbursed.

… The $10 billion fund target is inherently inadequate, as it does not provide for the cost of improving and expanding health care and education systems in developing countries. It is impossible to tackle HIV/AIDS without improving health care and education systems. The billions needed can only be met by governments increasing their aid budgets.

Christian Aid believes the AIDS fund is a diversion from tackling the root cause of the global AIDS crisis, which is poverty.

Tackling root causes is important because ignoring those would lead to the same problems recurring. The fund therefore, while perhaps still welcome (because we still need to deal with the immediate and massive problem) will always be fighting an uphill struggle.

Furthermore, there have also been continued concern over issues such as patents, pricing and so on. This is captured well by Philippe Riviére, who is worth quoting at length:

The Indian firm Cipla’s offer to MSF [Médecins sans frontiéres] to provide a cocktail of antiretrovirals for less than $350 a year (compared to the big boys’ $10,000) resounded like a thunderbolt. Suddenly, the emergence in the South of very low cost generics producers seems credible.

James Love, coordinator of the Consumer Project on Technology in Washington and kingpin of the Cipla offer, stresses:

The success in the developing world of the southern producers is quite important. Otherwise there is no real leverage. It is important not to link use of the global fund to purchases from European and US producers, but rather, to permit competition and buy from the firms with the best price that have acceptable quality. [Harvard economist, Jeffery] Sachs [leading a proposal from a group of researchers and international experts] has been terrible on this, urging purchases from big pharma exclusively.Is that why the Harvard mechanism found favour with the Bush administration, the European Commission, the WHO experts, UNAids, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the pharmaceutical industry? It offered an answer to

medical apartheidwithout dropping the guard on patents.(Emphasis Added)

The mention of the Gates Foundation above also raises notes about philanthropy, its pluses and minuses.

Private donations, especially large philanthropic donations and business givings, can be subject to political/ideological or economic end-goals and/or subject to special interest. A vivid example of this is in health issues around the world. Amazingly large donations by foundations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are impressive, but the underlying causes of the problems are not addressed, which require political solutions. As Rajshri Dasgupta comments:

Private charity is an act of privilege, it can never be a viable alternative to State obligations,said Dr James Obrinski, of the organisation Medicins sans Frontier, in Dhaka recently at the People’s Health Assembly (see Himal, February 2001). In a nutshell, industry and private donations are feel-good, short-term interventions and no substitute for the vastly larger, and essentially political, task of bringing health care to more than a billion poor people.

As another example, Bill Gates announced in November 2002 a massive donation of $100 million to India over ten years to fight AIDS there. It was big news and very welcome by many. Yet, at the same time he made that donation, he was making another larger donation—over $400 million, over three years—to increase support for Microsoft’s development suite of applications and its platform, in competition with Linux and other rivals. Thomas Green, in a somewhat cynical article, questions who really benefits, saying And being a monster MS [Microsoft] shareholder himself, a

(Emphasis is original.)Big Win

in India will enrich him [Bill Gates] personally, perhaps well in excess of the $100 million he’s donating to the AIDS problem. Makes you wonder who the real beneficiary of charity is here.

India has potentially one tenth of the world’s software developers, so capturing the market there of development platforms is seen as crucial. This is just one amongst many examples of what appears extremely welcome philanthropy and charity, but may also (not always) have other motives. It might be seen as horrible to criticize such charity, especially on a crucial issue such as AIDS, but that is not the issue. The concern is that while it is welcome that this charity is being provided, at a systemmic level, such charity is unsustainable and shows ulteria motives. Would Bill Gates have donated that much had there not been additional interests for the company that he had founded?

In addition, as award-winning investigative reporter and author Greg Palast also notes, the World Trade Organization’s Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the rule which helps Gates rule, also bars African governments from buying AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis medicine at cheap market prices

. He also adds that TRIPS is killing more people than the philanthropy saving. What Palast is hinting towards is the unequal rules of trade and economics that are part of the world system, that has contributed to countries such as most in Africa being unable to address the scourge of AIDS and other problems, even when they want to. See for example, the sections on free trade, poverty and corporations on this web site for more on this aspect.

Some two years on from the setting up of the Global Fund, and in 2003, the Fund is still facing cash short falls, and growing criticism about the way the U.S. and Europe have not been providing the money they claim to offer.

In May 2003, the US Congress passed a bill pledging $15 billion over the next five years to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria around the world. This was preceded by a prominent announcement by President Bush in his State of the Union speech. But behind the headlines, the five year plan has come under attack for largely by-passing the Global Fund, precisely set up as a functional and working multilateral program to fight fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Furthermore, the Fund has been facing an immediate fiscal shortfall of $700 million in 2003 alone, because the U.S. and other donors have not committed their fair share.

The alternative to the Global Fund the US decided to set up is known as PEPFAR (the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief). However, as the international HIV and AIDS charity AVERT criticizes, this allows the US to avoid supporting countries perceived to be hostile, or those who may support programs it currently does not like—such as abortion and condom use, or use of generic drugs). As above-mentioned Peris Jones also noted, USAID, the US aid agency responsible for enormous amounts of global aid flows and development projects, is finding that its policy is increasingly encroached upon and vulnerable to [a] domestic agenda

whereby the Christian Right has been increasingly influential on social issues in controversial ways. (Jones, pp.175-179)

Bush’s announcement of $15 billion sounded very welcome. It also showed up Europe to be lagging behind on their commitments too. Even France’s President Jacques Chirac conceded that Mr Bush’s pledge was

as Linda Bilmes noted in the Financial Times (July 6, 2003). The same article also noted that historic

and that Europe must do more

on HIVIn reality, nothing like $15bn will ever be spent

because of the failure to ask for the required amounts for each budget request. The article continues:

In January, Mr Bush promised to make a contribution of $1bn over five years to the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria. But the budget earmarks only the minimum $200m—far less than the $350m the US contributed to the fund last year. Nor is that all: even that $200m is made conditional on European nations matching every $1 that the US chips in with at least $2 of their own.

The president’s budget also imposes new restrictions on how existing US funds can be used. For example, there is a provision that directs a third of bilateral HIV/Aids money—about $130m—to be spent on

abstinence-until-marriageprogrammes. Such programmes may well have a role to play. But leading HIV/Aids medical groups, such as Physicians for Human Rights, have expressed concern that restrictions such as these will impede the overall prevention programme.

The above-mentioned $200 million is just 6.6% of what the Fund says it needs in 2004 ($3 billion) as detailed by Global AIDS Alliance, an organization dedicated to fighting global AIDS. The previous link is to a web page that introduces a PDF-formatted report, very critical of Bush’s $15 billion emergency plan. Amongst the criticism is that:

- The announcement of $15 billion dollars and the way it was presented was misleading:

While President Bush describes the Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief as a $15 billion response, which the general public, glancing at the headlines, can easily misinterpret to mean $15 billion all at once. Those with the patience to look into it find that the proposed spending is spread out over five years and that the $15 billion figure includes both existing spending levels as well as the President’s new proposal.

- The pace of action so far has actually been quite slow

- Other parts of the 2004 budget would be cut, which could also help in fighting poverty and other issues that are related to AIDS:

Cuts in the President’s FY04 budget request include Refugee Assistance (-2.8 percent), Development Assistance (-2.5 percent), other Global Health programs (-14.3 percent), and International Disaster Assistance (-18.3 percent). These cuts hurt the AIDS effort because AIDS is closely related to other health crises and rooted in poverty and inequality, oppression of women and girls.

- Hurting the Global Fund (as also mentioned above)

- Using

fuzzy math

to arrive at the $15. Amongst the criticism is that this amount was presented as a means to fight AIDS, yet some of this money also goes to research and fight other illnesses and disease. But,the point is not that research and funding for the fight TB and malaria are unnecessary. On the contrary, this funding is important and needed. It’s that this spending cannot count as progress toward spending goals that are specific to AIDS services. The spending target the US and other nations agreed to in the Declaration of Commitment at the UN General Assembly Special Session on HIV/AIDS (June 2001), $7 to 10 billion in annual spending by 2005, deliberately excludes research spending as well as spending on other diseases. The spending target is based on careful projections of what is needed to finance AIDS services alone. (Since 2001, the UN has revised its estimate of what is needed to fight AIDS. In October 2002 UNAIDS and the World Health Organization said $10.5 billion in annual spending would be needed by 2005

for a barebones package of prevention, treatment, care and support

and $15 billion in annual spending by 2007 to fight AIDS specifically.) - That even though the amount sounds high, the U.S. is actually not contributing its fair share. For example, Even though in the past significant resources have been contributed to fight other major diseases

President Bush describes the US as doing its fair share [in the fight against AIDS]… Yet, under the President Bush spending plan, the US will provide just $1.55 billion by 2005 for direct AIDS programs; that’s only 14.8% of what the UN says will be needed globally by that date for what it calls a

barebones package

to fight AIDS ($10.5 billion in annual spending). Even two years later, under the President’s plan only $2.64 billion will be provided for direct, on-the-ground AIDS programs, still only 17.6% of what the UN says will be needed globally by 2007 to fight AIDS specifically ($15 billion in annual spending on AIDS services). - There is

no clear plan to deepen debt relief for poor countries, despite the clear mandate contained in the AIDS Bill to do so, especially for AIDS-stricken countries.

The issue of third world debt is agreed by many to be a contributing factor that makes the AIDS problem even worse. As detailed in the AIDS section on this site, what makes this even worse is that much of this debt is unfair debt that the third world should not be paying anyway. - The U.S. has pushed via the WTO and outside of it, to prevent poor countries from producing cheaper, generic drugs to help tackle AIDS.

The criticism above from Bilmes, about determining how the fund will be used is also criticized by others, revealing other concerns. For example, writing in a guest editorial for OneWorld.net, Louise Richards, chief executive of War on Want writes that:

Only $10 billion of Bush’s pledged $15 billion is new. Second, as ActionAid has pointed out, there’s no guarantee that this money will be spent over the next five years….

There is also the question of whether the funds will be tied aid—a hallmark of US official development assistance. Revealingly, the USA has said it will deliver only one third of pledged dollars through the Global Fund, with the remaining money coming as bilateral aid. The Global Fund was set up specifically to be free of the conditionality associated with tied aid and it champions the purchase of the cheaper generic drug treatments central to fighting HIV/AIDS in the least-developed countries….

By opting for bilateralism, the USA will choose which countries to aid and which diseases to fight. The latter is largely defined by the research carried out by its domestic pharmaceutical industry.

Richards observes how politics comes into play in things like aid and charity. This is an enormous topic in its own right, but this site’s section on U.S. and Foreign Aid begins to look at this in more detail, on things like how aid is often tied to political agendas, that often end up benefiting the donor, not always the recipient.

In the same article, Richards also notes the influences of the pharmaceutical industry, and adds to the above that The USA’s bilateral pledge casts a long shadow over the current round of trade talks. Back at [the World Trade Organization round at] Doha in November 2001, developing countries were promised a deal to ensure their access to cheap drugs to fight public health emergencies. Since the poorest countries have no pharmaceutical industries, they depend on imports from countries with a generic drugs industry, especially India. But from 1 January 2006 countries such as India have agreed to implement the World Trade Organization’s full Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) agreement, making the export of generic treatments illegal.

In addition, President Bush had picked a former top executive of a major U.S. pharmaceutical company to head the U.S.’s global AIDS initiative, leading to further accusations of a commercial agenda, and lack of real experience in the issues that matter. (As well as the previous link, see for example, similar criticisms from Health GAP and Global Treatment Access Campaign, two organizations campaigning for global access to affordable medicines.)

A meeting in October 2003 resulted in donor countries pledging just $620 million for 2004, far short of the $10.5 billion needed per year, as sharply criticized by an article from Inter Press Service.

Such political pressure from corporate, ideological and related interests have been part of on-going issues for a number of years now while people are suffering from AIDS and other diseases that could otherwise be easily addressed. The corporations and medical research part of this site looks more into how large pharmaceutical companies have tried to thwart efforts of developing countries.

For more information:

- Related articles elsewhere on this site

- OneWorld and its partner organizations have been reporting on the issue of AIDS in developing countries for a number of years now. They have a number of major sections from where you can start:

- World Health Organization — within the WHO site, you will find many resources and links to other web sites.

- UNICEF’s Progress of Nations, 1999, has a section on the AIDS Emergency.

Deadly Conditions? Examining the relationship between debt relief policies and HIV/AIDS.

A report by Medact and the World Development Movement.- UN Development Program’s report,

Poverty & HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa

AIDS and the World Bank: Global Blackmail?

looks into some of the global politics at play and the effects of some reactions from South Africa’s president, Thabo Mbeki.- Durban 2000 March for HIV/AIDS treatment is a march against pharmaceutical giants and governments—planned to coincide with the opening day of the 13th International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa in July.

- The Panos Institute has a section on HIV/AIDS that provides a number of articles and resources.

- A number of articles from ZNet.

- UNAIDS, The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, provides a lot of informations, statistics and reports.

The Epidemic and the Media

from the MediaChannel.org provides a collection of articles looking at the role of the media in this issue.AIDS and the Poverty in Africa

, from The Nation Magazine, May 21 2001, looks at the relationship between poverty, and the lack of consideration of such aspects that has gone into current scientific research to explain the causes of the AIDS epidemic in Africa.- Health GAP, an organization campaigning for global access to affordable AIDS medicines.

- Global Treatment Access Campaign, an organization also campainging for affordable medicines for a variety of diseases.

- Global AIDS Alliance an organization dedicated to fighting global AIDS.

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated:

Global Issues

Global Issues