Action on climate change is cheaper than inaction

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/806/action-cheaper-than-inaction.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

On this page:

Cost of inaction on climate change far higher than the cost of action

A number of countries and companies have long been worried that the costs of tackling climate change (prevention, mitigation, adaptation, etc) will be prohibitive and would rather deal with the consequences. They often assume (or hope) the consequences will not be as bad as scientists are predicting.

As an example, in December 2011, Canada pulled out of the Kyoto climate treaty — which it is legally allowed to do — to condemnation domestically and internationally. One of the main concerns had been the cost to the tax payer: (CAN) $14bn.

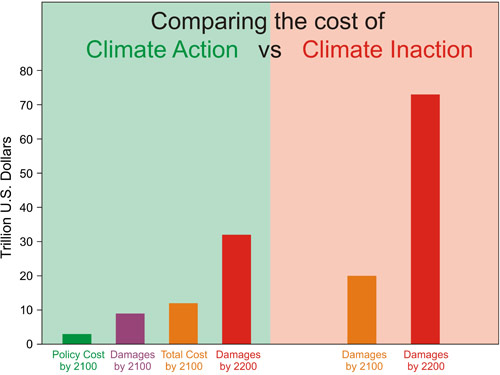

Yet, the economic costs of inaction are in the trillions:

(Some believe one of Canada’s motivations to leave Kyoto was on its desire to protect the lucrative but highly polluting exploitation of tar sands, the second biggest oil reserve in the world

, as The Guardian had noted.)

Concerns about costs often ignore the other benefits of action

Climate change problems also affect people’s health directly, as well as impacting the environment. For example, fossil fuels used by cars in heavily congested areas lead to additional pollutants harmful to human health. Tackling climate change by limiting fossil fuel use and investing heavily in alternatives has the additional benefit of improving health, and even possibly reducing traffic congestion. This is the view of some major reports recently released.

Economist Paul Krugman summarizes a couple:

A big study by a blue-ribbon international group, the New Climate Economy Project, and a working paper from the International Monetary Fund. Both claim that strong measures to limit carbon emissions would have hardly any negative effect on economic growth, and might actually lead to faster growth.

In effect, these studies are saying that not only could climate change costs be minimized through action, but it could turn into economic benefits.

Another concern by some countries is they can’t do things — even if they wanted to — because if other countries are not subjected to carbon emission reduction targets then they will lose out competitively. However, the IMF notes that the additional economic benefits of reducing carbon emissions make it worth pursuing with or without others doing it.

In the past, price signals have often missed out health and other consequences of certain economic actions. GNP and similar measures thus do not reveal the real costs in economic activity. In some cases it is even made to look the reverse. For example, a thriving industry selling unhealthy foods, plus the profits made by private health companies addressing the consequences, all help contribute to the GNP of a nation. The costs borne by society (the drain on public health resources, or various social and individual consequences, for example) are often not factored in.

Increasingly though, there are attempts to try and account for these things. In the biodiversity section of this site, there is a part discussing attempts to give biodiversity an economic value in order for businesses and governments to have a more tangible understanding of what value natural resources provide to our economy and well being, thus giving more tools and motivation to help preserve the environment and develop more sustainably.

And the above article by the IMF shows that with carbon pricing, the knock-on effects are more positive than inaction if you get the energy price right.

Many fossil fuel industries have been propped up by governments. Whether they would be able to compete against a growing renewables industry on its own is hard to know, but alternatively if the renewable sector were given the types of subsidies that fossil fuel industries receive then the costs of renewables would be even lower than they are already becoming.

In addition, the environmental and other costs from fossil fuel use are not factored into the prices we pay for this form of energy, making them artificially lower than they should be (even if we do feel energy costs may be high at the moment).

Paul Krugman summarizes these points by simply noting:

It’s easier to slash emissions than seemed possible even a few years ago, and reduced emissions would produce large benefits in the short-to-medium run. So saving the planet would be cheap and maybe even come free.

…

The idea that economic growth and climate action are incompatible may sound hardheaded and realistic, but it’s actually a fuzzy-minded misconception. If we ever get past the special interests and ideology that have blocked action to save the planet, we’ll find that it’s cheaper and easier than almost anyone imagines.

As explained in more detail on this site’s section on energy security, tackling climate change through addressing our use of fossil fuels may have some geopolitical benefits, too. For example, less reliance on fossil fuels could help reduce military and geopolitical involvement in other parts of the world, which itself is expensive. With less need for fossil fuels from volatile regions of the world, the support given to friendly autocratic and dictatorial regimes could dwindle. Maybe that would make it easier to support regimes that are more democratic and those who respect people’s rights more? Such benefits seem even harder to put an economic value to, but would seem well worth the effort?

Author and Page Information

- Created:

Global Issues

Global Issues