Mozambicans Living in the Shadow of a Secret State

MAPUTO, Jun 29 (IPS) - In downtown Maputo, the walls are covered with the local newspaper, Verdade, and a range of people, young and old, male and female, are reading it. Verdade, which means Truth in Portuguese, is a free weekly newspaper that is pasted on the walls of buildings in Mozambique's capital.

It is one of the most innovative, imaginative and, its publishers claim, widely-read newspapers in Mozambique. Aside from the 32-page hard copy of the newspaper, Verdade has a website, a dedicated mobile phone news site, and a presence on social network sites Twitter and Facebook.

All its news is sourced from the community, and people verify and correct the information online. There are no official figures of how many people have access to the internet in Mozambique, but it is estimated that one percent of the population is connected. Verdade also makes use of mobile phones. Citizen reporters, including taxi drivers and shopkeepers from all over this southern African nation, send text messages of their local news to Verdade's Maputo office.

This citizen journalism is considered key to Verdade's success. Until four years ago, the state-owned Noticias newspaper dominated Mozambican media. News was little more than propaganda. But with the Mozambican regional elections set for November, and the national elections for 2014, a spotlight has been placed on the issue of accessing information.

"Really this is the first election that we are covering what is happening in the country. Before, in 2008, we were just getting started. We just reported the final results. But now, after five years, the media is a tool for the transformation and development of the country. This election is one of the first steps," Verdade's editor-in-chief Adérito Caldeira told IPS.

One of the jobs for the Verdade team will be to ensure polling stations are open, that people know how to use them, and that the election data is reliably relayed.

But also, for the elections to be effective, people must be aware of the issues and what they are voting for.

Mozambique is over 800,000 square kilometres, almost twice the size of neighbouring Zimbabwe, and this makes getting news out and spreading information a real challenge.

Added to this is the fact that 60 percent of Mozambicans are illiterate, and only 10 percent of the country's almost 24 million people have access to electricity, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

And, according to the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA), there is a legal vacuum surrounding the right to information, "which is becoming a serious obstacle to the credibility of the state and to achieving the other fundamental rights and freedoms that are connected to the right to information."

No Freedom to Access Information

Over 20 civil society groups, spearheaded by MISA, have been trying for the last seven years to get the Freedom of Information Bill through parliament.

According to MISA, the bill "will allow the state to bring the voice of the people into the development processes, opening the path to ensure that all vital forces in society, and particularly vulnerable groups, have a word to say."

Anthropologist Luka Mucavele told IPS: "The bill will allow access to state files and records, which is a step towards the dismantling of the centralised socialist state. But of course its success rests completely on people knowing they have a right to information, and that they have the time and inclination to pursue this."

Yveth Matunza, a lawyer at the Mozambican Human Rights League, is worried. "Identity and information are linked. We do have an exemplary constitution here in Mozambique, so the machinery exists. However, most people here don't know their rights, information is presented in a biased way, and is not explained well," she told IPS.

"We have a lot of problems when it comes to accessing information. We don't know when the Freedom of Information Act will become law. We only know it's on the agenda. Even if this law passes, I don't believe it will give us access to information," said Matunza who, in her spare time, is also one Mozambique's two female rappers.

The bill contains public interest clauses that could override claims of national security or commercial secrecy where public health, environmental dangers, or human rights violations are involved.

Free speech key to Mozambique's development

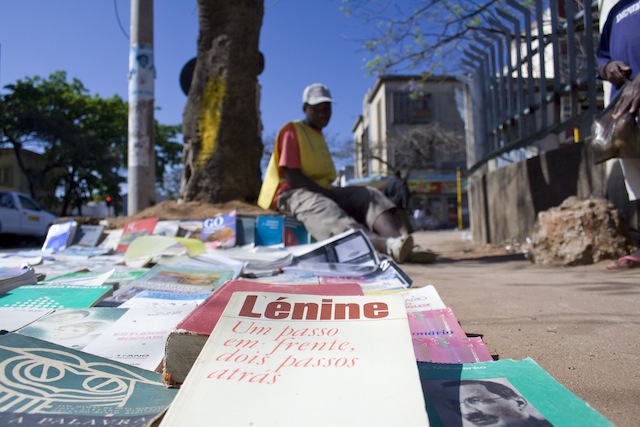

There are now four private newspapers in Mozambique, many bookshops, numerous cafes, and exhibition venues, including the French Cultural Institute. However, these are in centralised Maputo and the challenge of informing the rural electorate about the issues remains huge, Mucavele said.

Joaquim Chissau is the owner and editor of Zambeze, one of the other private newspapers in Maputo.

"Expressing our national identity is very important. Since the death of Carlos Cardoso (a journalist investigating government fraud who was shot outside his home in a Maputo suburb) in 2000 we have definitely seen a big improvement in debate," he told IPS.

"Discussion and debate are a very important part of Mozambican society … there are big discussions we need to have, particularly on the role of oil and gas, and the opposition party, Renamo (Mozambican National Resistance) in Mozambique."

Renamo has threatened to unleash violence across the country if the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front, known by its Portuguese acronym Frelimo, does not loosen its control on politics and the economy. Since April, there have been repeated skirmishes with both sides, and 11 soldiers and five civilians have been killed to date.

Ivan Levanjeira was born and raised in Mafalala, a township on the outskirts of Maputo and runs the only community tourism initiative in Mozambique. For him, freedom of speech and expression is key to Mozambique's development. "We are a diverse community, very politicised, our grandparents were forced immigrants. We know our history, and we know our rights."

But architecture student Walter Tembe is less enthusiastic.

"The economic boom is only for a very, very few… People are worried about getting their next meal. Most of us are blind, we don't know what's going on, and if we question too much there's trouble."

© Inter Press Service (2013) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues