Soaring Child Poverty – a Blemish on Spain

MALAGA, Spain, Apr 09 (IPS) - "I don't want them to grow up with the notion that they're poor," says Catalina González, referring to her two young sons. The family has been living in an apartment rent-free since December in exchange for fixing it up, in the southern Spanish city of Málaga.

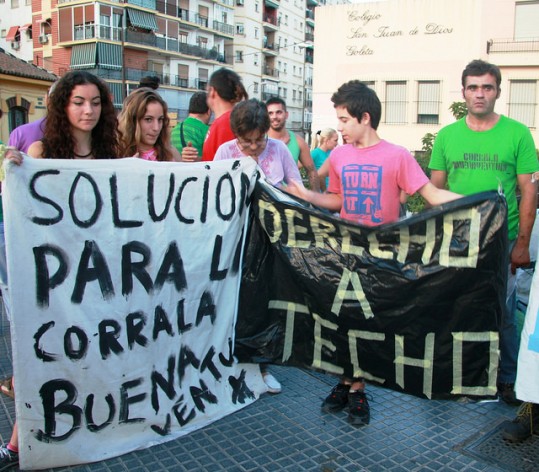

Six months ago González, 40, and her two sons, Manuel and Leónidas, 4 and 5, were evicted by the local authorities from the Buenaventura "corrala" or squat - an old apartment building with a common courtyard that had been occupied by 13 families who couldn't afford to pay rent. The evicted families included a dozen children.

Since then, she told IPS, her sons "don't like the police because they think they stole their house."

Spain has the second-highest child poverty rate in the European Union, following Romania, according to the report "The European Crisis and its Human Cost – A Call for Fair Alternatives and Solutions" released Mar. 27 in Athens by Caritas Europa.

Bulgaria is in third place and Greece in fourth, according to the Roman Catholic relief, development and social service organisation.

The austerity measures imposed in Europe, aggravated by the foreign debt, "have failed to solve problems and create growth," said Caritas Europa's Secretary General Jorge Nuño at the launch of the report.

"We're doing ok. The kids are already pre-enrolled in school for the next school year," said González, a native of Barcelona, who left the father of her sons in Italy when she discovered that "he mistreated them."

She started over from scratch in Málaga, with no family, job or income, meeting basic needs thanks to the solidarity of social organisations and mutual support networks.

According to a report published this year by the United Nations children's fund UNICEF, in 2012 more than 2.5 million children in Spain lived in families below the poverty line – 30 percent of all children.

UNICEF reported that 19 percent of children in Spain lived in households with annual incomes of less than 15,000 dollars.

"Child poverty is a reality in Spain, although politicians want to gloss over it and they don't like us to talk about it because it's associated with Third World countries," the founder and president of the NGO Mensajeros de la Paz (Messengers of Peace), Catholic priest Ángel García, told IPS.

Spain's finance minister Cristóbal Montoro said on Mar. 28 that the information released by Caritas Europa "does not fully reflect reality" because it is based solely on "statistical measurements."

But in Málaga "there are more and more mothers lining up to get food," Ángel Meléndez, the president of Ángeles Malagueños de la Noche, told IPS.

Every day, his organisation provides 500 breakfasts, 1,600 lunches and 600 dinners to the poor.

For months, González and her sons have been taking their meals at the "Er Banco Güeno", a community-run soup kitchen in the low-income Málaga neighbourhood of Palma-Palmilla, which operates out of a closed-down bank branch.

According to Father Ángel, child poverty "isn't just about not being able to afford food, but also about not being able to buy school books or not buying new clothes in the last two years."

"It's about unequal opportunity among children," he said.

The crisis in Spain is still severe. The country's unemployment rate is the highest in the EU: 25.6 percent in February, after Greece's 27.5 percent.

In 2013, the government of right-wing Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy approved a National Action Plan for Social Inclusion 2013-2016, which includes the aim of reducing child poverty.

Caritas Europa reports that at least one and a half million households in Spain are suffering from severe social inclusion - 70 percent more than in 2007, the year before the global financial crisis broke out.

"Entire families end up on the street because they can't afford to pay rent," Rosa Martínez, the director of the Centro de Acogida Municipal, told IPS during a visit to the municipal shelter. "More people are asking for food. They're even asking for diapers for newborns because they are in such a difficult situation."

Of the nearly 26 percent of the economically active population out of jobs, half are young people, according to the National Statistics Institute, while the gap between rich and poor is growing.

As of late March, 4.8 million people were unemployed, according to official statistics. The figures also show that the proportion of jobless people with no source of income whatsoever has grown to four out of 10.

Social discontent has been fuelled by austerity measures that have entailed cutbacks in health, education and social protection.

A report on the Housing Emergency in the Spanish State, by the Platform for Mortgage Victims (PAH) and the DESC Observatory, estimates that 70 percent of the families who have been, or are about to be, evicted include at least one minor.

"The right to equal opportunities is dead letter if children are ending up on the street," José Cosín, a lawyer and activist with PAH Málaga, told IPS.

Cosín denounced the vulnerable situation of the children who were evicted along with their families from the Buenaventura corrala on Oct. 3, 2013.

Fifteen of the people who were evicted filed a lawsuit demanding respect of the children's basic rights, as outlined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which went into effect in 1990.

The Convention establishes that states parties "shall in case of need provide material assistance and support programmes, particularly with regard to nutrition, clothing and housing."

The number of families in Spain with no source of income at all grew from 300,000 in mid-2007 to nearly 700,000 by late 2013, according to the report Precariedad y Cohesión Social; Análisis y Perspectivas 2014 (Precariousness and Social Cohesion; Analysis and Perspectives 2014), by Cáritas Española and the Fundación Foessa.

And 27 percent of households in Spain are supported by pensioners. Grown-up sons and daughters are moving back into their parents' homes with their families, or retired grandparents are helping support their children and grandchildren, with their often meagre pensions.

"When times get rough, the social fabric is strengthened," said González. She stressed the solidarity of different groups in Málaga who for three months helped her clean up and repair the apartment she is living in now, which is on the tenth floor of a building with no elevator, and was full of garbage and had no door, window panes or piped water.

González complained that government social services are underfunded and inefficient, and said she receives no assistance from them.

Like all young children, her sons ask her for things. But she explains to them that it is more important to spend eight euros on food than on two plastic fishes. It took her several weeks to save up money to buy the toys. Last Christmas she took them to a movie for the first time.

© Inter Press Service (2014) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues