China Drives Nuclear Expansion in Argentina, but with Strings Attached

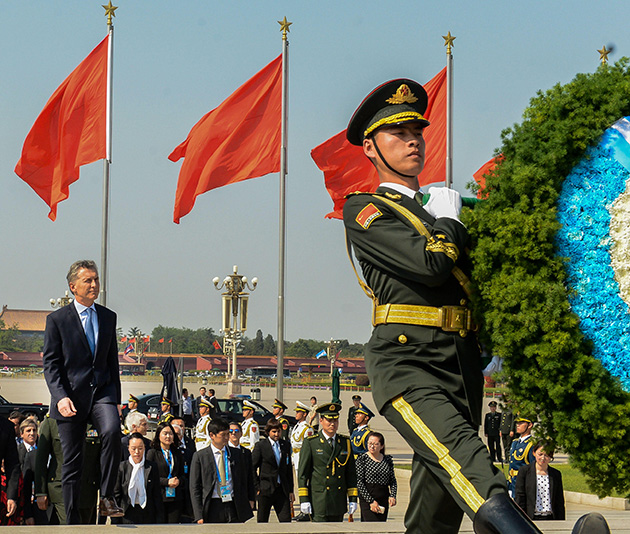

Two new nuclear power plants, to cost 14 billion dollars, will give a new impetus to Argentina's relation with atomic energy, which began over 60 years ago. President Mauricio Macri made the announcement from China, the country that is to finance 85 per cent of the works.

But besides the fact that social movements quickly started to organise against the plants, the project appears to face a major hurdle.

The Chinese government has set a condition: it threatens to pull out of the plans for the nuclear plants and from the rest of its investments in Argentina if the contract signed for the construction of two gigantic hydroelectric power plants in Argentina's southernmost wilderness region, Patagonia, does not move forward. The plans are currently on hold, pending a Supreme Court decision.

Together with Brazil and Mexico, Argentina is one of the three Latin American countries that have developed nuclear energy.

The National Commission for Atomic Energy was founded in 1950 by then president Juan Domingo Perón (1946-1955 and 1973-1974) and the country inaugurated its first nuclear plant, Atucha I, in 1974. The development of nuclear energy was halted after the 1976-1983 military dictatorship, by then-president Raúl Alfonsín (1983-1989), but it was resumed during the administration of Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007).

According to the announcement Macri made during his visit to Beijing in May, construction of Atucha III, with a capacity of 745 MW, is to begin in January 2018, 100 km from the capital, in the town of Lima, within the province of Buenos Aires.

Atucha I and II, two of Argentina's three nuclear power plants, are located in that area, while the third, known as Embalse, is in the central province of Córdoba.

Construction of a fifth nuclear plant, with a capacity of 1,150 MW, would begin in 2020 in an as-yet unannounced spot in the province of Río Negro, north of Patagonia.

Currently, nuclear energy represents four per cent of Argentina's electric power, while thermal plants fired by natural gas and oil account for 64 per cent and hydroelectric power plants represent 30 per cent, according to the Energy Ministry. Other renewable sources only amount to two per cent, although the government is seeking to expand them.

Besides diversifying the energy mix, the projected nuclear and hydroelectric plants are part of an ambitious strategy that Argentina set in motion several years ago: to strengthen economic ties with China, which would buy more food from Argentina and boost investment here.

During his May 14-17 visit to China, Macri was enthusiastic about the role that the Asian giant could play in this South American country.

"China is an absolutely strategic partner. This will be the beginning of a wonderful era between our countries. There must be few countries in the world that complement each other than Argentina and China," said Macri in Beijing, speaking to businesspeople from both countries.

"Argentina produces food for 400 million people and we are aiming at doubling this figure in five to eight years," said Macri, who added that he expects from China investments in "roads, bridges, energy, ports, airports."

Ties between Argentina and China began to grow more than 10 years ago and expanded sharply in 2014, when then president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-2015) received her Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in Buenos Aires, where they signed several agreements.

These ranged from the construction of dams in Patagonia to investments in the upgrading of the Belgrano railway, which transports goods from the north of the country to the western river port of Rosario, where they are shipped to the Atlantic Ocean and overseas.

On Jun. 22, 18 new locomotives from China arrived in Buenos Aires for the Belgrano railroad.

However, relations between China and Argentina are not free of risks for this country, experts warn.

"China has an almost endless capacity for investment and is interested in Argentina as in the rest of Latin America, a region that it wants to secure as a provider of inputs. Of course China has strong bargaining powers and Argentina's aim should be a balance of power," economist Dante Sica, who was secretary of trade and industry in 2002-2003, told IPS.

"They are buyers of food, but they also want to sell their products and they generate tension in Argentina´s industrial structure. In fact, our country for several years now has had a trade deficit with China," he added.

Roberto Adaro, an expert on international relations at the Centre for Studies in State Policies and Society, told IPS that "Argentina can benefit from its relations with China if it is clear with regard to its interests. It must insist on complementarity and not let China flood our local market with their products."

Adaro praised the decision to invest in nuclear energy since it is "important to diversify the energy mix" and because the construction of nuclear plants "also generates investments and jobs in other sectors of the economy."

However, there is a thorn in the side of relations between China and Argentina regarding the nuclear issue: the project of the hydroelectric plants. These two giant plants with a projected capacity of 1,290 MW are to be built at a cost of nearly five billion dollar, on the Santa Cruz River, which emerges in the spectacular Glaciers National Park in the southern region of Patagonia, and flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

In December, when the works seemed about to get underway, the Supreme Court suspended construction of the dams, in response to a lawsuit filed by two environmental organisations.

The three Chinese state banks financing the two projects then said they would invoke a cross-default clause included in the contract for the dams, which said they would cancel the rest of their investments if the dams were not built.

To build the two plants, three Chinese and one Argentine companies formed a consortium, but after winning the tender in 2013, construction has not yet begun.

Under pressure from China, the government released the results of a new environmental impact study on Jun. 15 and now plans to convene a public hearing to discuss it, so that Argentina's highest court will authorise the beginning of the works.

Added to opposition to the dams by environmentalists is their rejection of the nuclear plants. In the last few weeks, activists from Río Negro have held meetings in different parts of the province, demanding a referendum to allow the public to vote on the plant to be installed there.

They have even generated an unusual conflict with the neighbouring province of Chubut, where the regional parliament unanimously approved a statement against the nuclear plants. The governor of Río Negro, Alberto Weretilnek, asked the people of Chubut to "stop meddling."

"Argentina must start a serious debate about what these plants mean, at a time when the world is abandoning this kind of energy. We need to know, among other things, how the uranium that is needed as fuel is going to be obtained," the director of the Environment and Natural Resources Foundation, Andrés Nápòli, told IPS.

Argentina now imports the uranium used in the country's nuclear plants, but environmentalists are worried that local production, which was abandoned more than 20 years ago, will restart.

© Inter Press Service (2017) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues