From the Syrian War to Argentina - Or How to Start a New Life

Fares, his father Hatem Badwan, his mother Tereza and his siblings Osama (26), Nansy (19) and Daniyal (12) are six of the nearly 2,000 Syrians who have settled in Argentina since the civil war began, some of them thanks to a programme sponsored by the government, although most came as refugees or through family reunification visas.

Adaptation to life in this South American country, which for many Syrian immigrants has been hard, is going well for this family.

That, at least, is what is perceived by those who visit Al Fares, the Middle Eastern food restaurant on Aráoz Street, in Villa Crespo, a middle-class neighbourhood in Buenos Aires, where the family cooks and serves, receiving constant shows of affection from clients.

"I buy the meat and vegetables here in Buenos Aires. But the spices are brought to me from Syria or Lebanon," said Hatem, the father, when asked about the secrets of the restaurant's dishes. "I taught those who work with me to cook the Arabic dishes. But I always add the spices," he clarifies.

Hatem and his wife have learned Spanish - which he speaks much better than she does - on the go, working in the restaurant, while their younger children have learned it at the school of the local Greek community that they attend, which is affiliated with the religion practiced by a large percentage of the Syrian population, Orthodox, although the family declares themselves Roman Catholic.

The Argentine government launched the Syria Programme in 2014, a humanitarian initiative by which some 390 Syrian citizens have entered the country, explained Federico Agusti, director of International Affairs in the National Immigration Office.

"The integration process is complex, because cultural differences in some cases generate episodes of stress or depression. Not to mention the difficulties of insertion in the labour market or, in the case of children, in school," the official told IPS.

For that reason Argentina offers an intercultural workshop in Beirut to prepare those who are going to emigrate, which provides information on subjects ranging from "how to use public transport in Argentina to the tradition of sharing 'yerba mate' (an infusion) among many people," Agusti added.

Fares al Badwan arrived before the launch of the Syria Programme, when the world was just beginning to hear about the terrible situation in that Middle Eastern country, which in recent years has cost the lives of millions of people and has driven many others from their homes.

"I was working as a waiter at a restaurant in Damascus. One day, at the beginning of the war, a bomb exploded which broke all the glass in the restaurant. After that the business lost many of its customers and everything went downhill," said Fares.

The teenager was already old enough to be called up for military service, so his father convinced him to go to Argentina, where his uncle Samir had been living for years. "If he became an army soldier, probably within a few days they would bring him back to me dead," said Hatem.

That is how Fares came to this country, got a job in a clothing factory with the help of his uncle, and later stopped being an employee and started to run his own textile business, thanks to which he sent money to his family in Syria, who were suffering the harsh effects of a war economy.

Finally, three years ago, when his parents arrived in Argentina with their two youngest children, they all set up a family restaurant in an old house that they rented.

"When we opened, since we did not have enough money, we could not buy enough glasses. But people did not complain and drank beer directly from the bottle," said Fares smiling, recalling the early days of their business.

Now the restaurant has built a reputation among many people and even had the luxury of providing the food served during one of the most popular Argentine television programmes, called "We Can Talk."

Regular diners repeat to IPS the same concepts: that in the restaurant "the food is homemade, delicious, the prices are good and the family is very hospitable".

The Syria Programme, still in force in Argentina, is based on the so-called "callers", who are individuals or institutions that, in solidarity, volunteer to host Syrian immigrants and help them settle in.

"Usually in resettlement, it is the host country that bears the costs of transportation, lodging and food upon arrival. Because it was too expensive, we looked for private sponsors," Agusti told IPS.

One of them is Mariano Winograd, who in 2017 lent his house to a Syrian couple, and founded an organisation called Argentine Humanitarian Shelter, whose mission is to encourage more "callers" to get involved.

"Argentine society has welcomed them well. I have not seen a single episode of discrimination against Syrians," said Winograd.

"Some adapted very well and others not so much. A number of them returned to their country, after complaining about inflation and insecurity in Argentina. It is hard to understand that they prefer to live among the bombs, but that is what they did," he added.

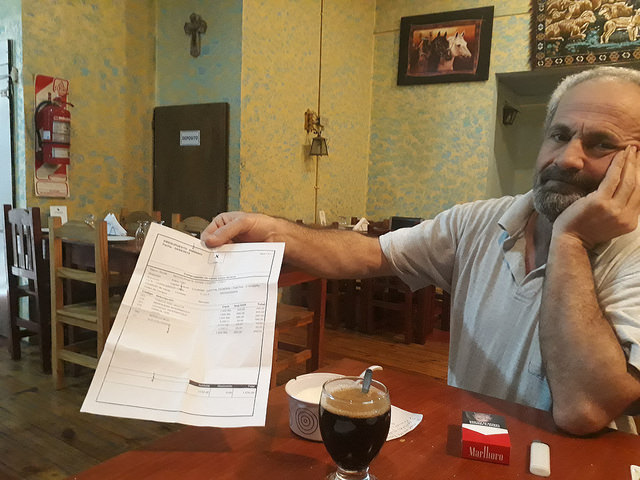

The steady increase in prices is a leading concern shared by local residents in Argentina and by Syrians like Hatem Badwan, who points to the cigarettes he smokes, to illustrate.

"When I had just arrived in Argentina, I used to buy two packets for 14 pesos. Now I pay 68 pesos for one pack. And electricity and natural gas rates have increased by 2,000 percent in the last two years," said Hatem.

His son Fares, on the other hand, does not seem to see much of a problem: "If you need more money you work more and you get it," he said.

The young man told IPS that he is thinking of launching another gastronomic venture in the trendy Buenos Aires neighbourhood of Palermo, which would not only offer Arabic food, but also a chance to smoke "narghile", the traditional pipe smoked in the Middle East and North Africa.

Argentine President Mauricio Macri promised in 2016, in the United Nations, that Argentina would welcome 3,000 immigrants through the Syria Programme. The initiative, however, is moving very slowly.

Sociologist Lelio Mármora, director of the Migration and Asylum Policy Institute of the 'Tres de Febrero' National Universit, underscores, however, that the programme was created during the previous government of Cristina Fernández, and that it has been maintained by the current administration, which is not common in Argentina when the presidents are from rival parties.

"It shows that it is a state policy. And while the number of Syrians that Argentina has received is very small, we must bear in mind that other countries, such as Hungary, have not wanted to receive any," said Mármora.

"Argentina is a country that has traditionally welcomed everybody. No political party here talks about the migration issue, and if someone did, they would lose every election. Our identity is linked to migration," he said.

© Inter Press Service (2018) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues