Community Management, Outmigration Help Nepal Double Forest Area

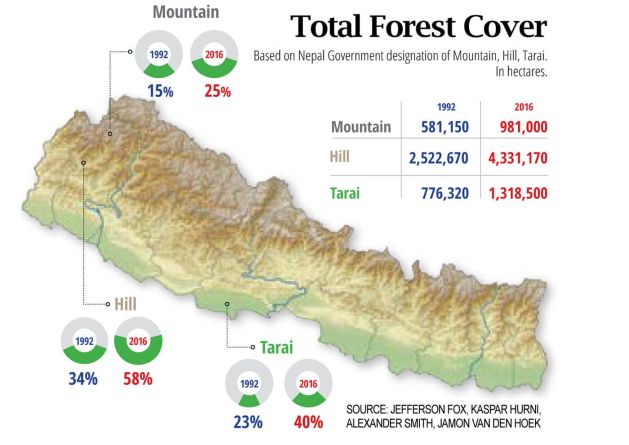

KATHMANDU, Sep 19 (IPS) - New analysis of historical satellite imagery indicates that Nepal's forest area has nearly doubled, from 26% of land area in 1992 to 45% in 2016. The midhills have experienced the strongest resurgence, although forests have also expanded in the Tarai and in the mountains. This makes Nepal an exception to the global trend of deforestation in developing countries.

These findings may come as a surprise to readers who regularly hear about deforestation. Indeed, recent infrastructure expansion projects seem to pit development against nature. Protesters have pushed back against the felling of trees for the Ring Road expansion project in Kathmandu, as well as the plan to cut down 8,000ha of jungle in Bara district for a proposed airport in Nijgad.

But the new research, conducted by a NASA-funded team whose members are based in the US, Switzerland and Nepal, does not indicate that Nepal has been free from deforestation in recent decades. Rather, the data show that on average, more new forests have grown up than have been cut down. As a result, there has been net forest gain.

Jefferson Fox, a geographer at the East-West Center in Honolulu who is the project's principal investigator, thinks it is important to acknowledge Nepal's forest successes, even if localised deforestation remains a problem in parts of the country.

"When I did my dissertation work in the early 1980s, Nepal was all over the international press for deforestation," he says. "Now that Nepal has turned it around, it can't get any attention!"

From 1950 to 1980, Nepal lost much of its forest cover. Deforestation was due in part to a growing rural population that cut trees to harvest timber and convert land to agriculture. Nepal had nationalised all forests in the 1950s, but the government was often ill-equipped to oversee them. Bureaucrats were frequently unaware, or turned a blind eye, when villagers cut trees for household use, and sometimes they colluded with commercial loggers to illegally exploit timber.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the government began handing over what eventually amounted to 1.8 million hectares of national forest land to communities to manage. Unlike government officials, local communities were seen to have a vested interest in preserving forest resources for long-term, sustainable use. They also were better positioned to monitor forests and enforce rules for harvesting forest products.

Fox's research team found that areas with high rates of community forest membership experienced the most forest recovery, implying that decentralised forest management has played a key role in Nepal's reforestation.

Demographic changes have also been important to forest recovery. Although Nepali villagers have migrated to India for seasonal and military work for centuries, migration to Gulf countries, Southeast Asia and beyond has exploded since the 1990s.

Migrants' families often abandon marginal farmland because they lack the manpower to use it, allowing forests to naturally regenerate. Likewise, the families often harvest fewer forest products, like firewood, because they have more money to purchase alternatives, such as LPG. Fox's team found that areas of Nepal where people receive the most remittances have also experienced greatest reforestation.

The data also indicate that Nepal's forest gains have been concentrated in the midhills. This is not surprising, because community forests are widespread in this region and outmigration and agricultural land abandonment are increasingly common. The data also show that forests have expanded in the Tarai, despite greater population growth, fewer community forests and more conflicts over resources there. However, gains in the Tarai — and in the mountains — have been smaller than in the midhills.

Importantly, forest extent is not the same thing as ecological value, which can vary greatly from forest to forest. For example, young, dry, and isolated forests do not provide as good wildlife habitat as old-growth and riverine forests, or forests located along wildlife corridors. Similarly, a forest on a steep slope helps reduce soil erosion, giving it conservation value that a forest in a flat area may not have.

Fox's team is not the first to analyse Nepal's forest cover change using satellite imagery. A group at the University of Maryland (GlobalForestWatch.org) has monitored forest change globally since 2000. In Nepal, its data show there has been forest loss — the opposite of Fox's team's findings. This data has been cited by numerous academic studies and the media, including this newspaper.

Both the old and new data were generated using computer algorithms that look at historical satellite images to determine — based on the colour and shade of pixels in each photograph — what is forest and what is not. Forests are considered to be any area with at least 50% canopy cover — meaning that, looking from the air, at least half of the ground is obscured by trees. (This may not sound like much, but the FAO standard is only 10%.)

While the Maryland team used algorithms designed for application around the world, Fox's team have created algorithms specifically tailored for Nepal. Alex Smith, a member of Fox's team who is also a PhD candidate at Oregon State University and a current Fulbright-Hays scholar in Kathmandu, says that image-analysis algorithms designed for worldwide use can be inaccurate in Nepal because of the mountainous terrain.

By contrast, his team's algorithms use topographic correction techniques to compensate for shade and other visual distortions caused by steep slopes. Furthermore, they ensure their algorithms are accurate by cross-analysing results with other high-resolution photographs of the same areas — a process known as ‘ground truthing'. For these reasons, the results are probably far more accurate for Nepal than the University of Maryland data.

Some would argue that because Nepal nearly doubled its forest area since 1992, it can spare a few thousand hectares here or there for infrastructure projects like Nijgad. But according to Smith, this is not the upshot of his team's research.

"Our study provides a big-picture view about what is happening, but the decision to convert any specific forest should be taken after considering local factors as well," he says.

These might include the potential benefits of the infrastructure project weighed against the value of the forest as wildlife habitat and as a source of resources, cultural values and aesthetics for local people.

Infrastructure aside, some people argue Nepal should allow more timber harvesting, which has hitherto been tightly regulated, as long as it is accompanied by sustainable forest management. Proponents of this approach say that forest-based industries could boost the economy without leading to deforestation, because trees would be replanted once cut.

Sceptics counter that ensuring long-term sustainability would be difficult, given pervasive problems with corruption and short-term thinking among leadership.

The new research by Fox's team does not provide conclusive evidence for one side or the other. Decisions about how much, and where, to harvest will inevitably involve balancing conservation and development objectives.

However, the research does highlight the continued importance of community forestry. "Local communities have put in a huge amount of effort conserving these forests," says Smith. "Whatever happens next, you want to keep people invested."

This story was originally published by The Nepali Times

© Inter Press Service (2019) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues