Women in Peru's Poor Urban Areas Combat the Crisis at the Cost of Their Wellbeing

CALLAO, Peru, Jul 03 (IPS) - At five in the morning, when fog covers the streets and the cold pinches hard, Mercedes Marcahuachi is already on her feet ready to go to work in Pachacútec, the most populated area of the municipality of Ventanilla, in the province of Callao, known for being home to Peru's largest seaport.

"If I don't get up that early, I don't have enough time to get everything done," the 55-year-old woman tells IPS as she shows us the area of her home where she runs a soup kitchen that she opened in 2020 to help feed her community during the COVID pandemic and that she continues to run due to the stiffening of the country's economic crisis.

Emerging as a special low-income housing project in the late 1980s, it was not until 2000 that the population of Pachacútec began to explode when around 7,000 families in extreme poverty who had occupied privately-owned land on the south side of Lima were transferred here by the then government of Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000).

The impoverished neighborhood is mainly inhabited by people from other parts of the country who have come to the capital seeking opportunities. Covering 531 hectares of sandy land, it is home to some 180,000 people, about half of the more than 390,000 people in the district of Ventanilla, and 15 percent of the population of Callao, estimated at 1.2 million in 2022.

Marcahuachi arrived here at the age of 22 with the dream of a roof of her own. She had left her family home in Yurimaguas, in the Amazon rainforest region of Loreto, to work and become independent. And she hasn't stopped working since.

She now has her own home, made of wood, and every piece of wall, ceiling and floor is the result of her hard work. She has two rooms for herself and her 18-year-old son, a bathroom, a living room and a kitchen.

"I'm a single mother, I've worked hard to achieve what we have. Now I would like to be able to save up so that my son can apply to the police force, he can have a job and with that we will make ends meet," she says.

Marcahuachi worked for years as a saleswoman in a clothing store in downtown Lima, adjacent to Callao, and then in Ventanilla until she retired. Three years ago, she created the Emmanuel Soup Kitchen, for which the Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion provides her with non-perishable food.

The community soup kitchen operates at one end of the courtyard that surrounds her house and offers 150 daily food rations at the subsidized price of three soles (80 cents of a dollar), which she uses to buy vegetables, meat and other products used in the meals.

Marcahuachi feels good that she can help the poorest families in her community. "I don't earn a penny from what I do, but I am happy to support my people," she says.

Her daily routine includes running her own home as well as ensuring the 150 daily food rations in the Emmanuel settlement where she lives, one of 143 neighborhoods in Pachacútec.

Various studies, including the World Bank's "Rising Strong: Peru Poverty and Equity Assessment", have found that poverty in Peru is mostly urban, contrary to most Latin American countries, a trend that began in 2013 and was accentuated by the pandemic.

By 2022, although the national economy had rallied, the quality of employment and household income had declined.

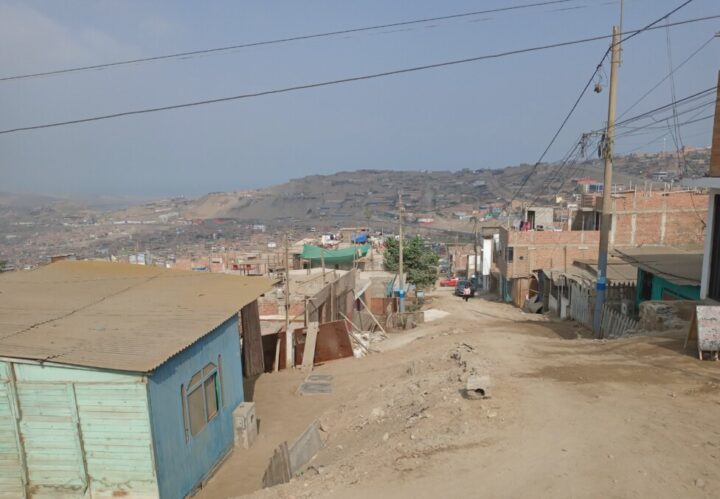

In Pachacútec, in the extreme north of Callao, the hardship is felt on a daily basis.

Only the two main streets are paved, while the countless steep lanes lined with homes are stony or sandy. Cleaning is constant, as dust seeps through the cracks in the wooden walls and corrugated tin-sheet roofs.

In addition, food and other basic goods stores are far away, so it is necessary to take public transportation there and back, which makes daily life more expensive and complicated.

But these are unavoidable responsibilities for women, who because of their stereotypical gender roles are in charge of care work: cleaning, washing, grocery shopping, cooking, and caring for children and adults with disabilities or the elderly.

This is the case of Julia Quispe, who at the age of 72 is responsible for a number of tasks, such as cooking every day for her family, which includes her husband, her daughter who works, and her four grandchildren who go to school.

She tells IPS that she has uterine prolapse, that she is not feeling well, but that she has stopped going to the hospital because for one reason or another they don't actually provide her with the solution she needs.

Despite her health problems, she does the shopping every day at the market, as well as the cooking and cleaning, and she takes care of her grandchildren and her husband, who because of a fall, suffers from a back injury that makes it difficult for him to move around.

"When we came here in 2000 there was no water or sewage, life was very difficult," she says. "My children were young, my women neighbors and I helped each other to get ahead. Now we are doing better luckily, but I can't use the transportation to get to the market; I can't afford the ticket, so I save by walking and on the way back I take the bus because I can't carry everything, it's too heavy."

But when it comes to talking about herself, Quispe says she never worked, that she has only dedicated herself to her home, replicating the view of a large part of society that does not value the role of women in the family: feeding, cleaning the house, raising children and grandchildren, providing a healthy environment, which includes tasks to improve the neighborhood for the entire community.

Moreover, in conditions of poverty and precariousness, such as those of Pachacútec, these tasks are a strenuous responsibility at the expense of their own well-being.

Recognizing women's care work

"Poor urban women have come from other regions and have invested much of their time and work in building their own homes, caring for their children and weaving community, a sense of neighborhood. They have less access to education, they earn low wages and have no social coverage or breaks, so they are also time poor," Rosa Guillén, a sociologist with the non-governmental Gender and Economics Group, tells IPS.

"For years, they have taken care of their families, their communities, they do productive work, but it is a very slow and difficult process for them to pull out of poverty because of inequalities associated with their gender," she says.

She adds that "even so, they plan their families, they invest the little they earn in educating their children, fixing up their homes, buying sheets and mattresses; they are always thinking about saving up money for the children to study during school vacations."

From the focus of the approach of feminist economics, she argues that it is necessary for governments to value the importance of the work involved in caregiving, in taking care of people, families, communities and the environment for the progress of society and to face climate change, investing in education, health, good jobs and real possibilities for retirement.

Ormecinda Mestanza, 57, has lived in Pachacútec for nine years. She bought the land she lives on but does not have the title deed; a constant source of worry, because besides having to work every day just to get by, she has to fit in the time to follow up on the paperwork to keep her property.

"It makes you want to cry, but I have to get over it, because this little that you see is all I have and therefore is the most precious thing to me," she tells IPS inside her wooden shack with a corrugated tin roof.

Everything is clean and tidy, but she knows that this won't last long because of the amount of dust that will soon cover her floor and her belongings, which she will just have to clean over again.

She works in Lima, as a cleaner in a home and as a kitchen helper in a restaurant, on alternate days. She gets to her jobs by taking two or three public transportation buses and subway trains, and it takes her two to three hours to get there, depending on the traffic.

"I get up at five in the morning to get ready and have breakfast and I get to work late and they scold me. 'Why do you come so far to work?' they ask me, but it's because the daily pay in Pachacútec is very low, 30 or 40 soles (10 to 12 dollars a day) and that's not enough for me," she says.

She managed to buy the land with the help of relatives. After working for a family as a domestic for 30 years, her employers moved abroad and she discovered that they had lied to her for decades, claiming to be making the payments towards her retirement pension. "I never thought I would get to this age in these conditions, but I don't want to bother my son, who has his own worries," she says.

According to official figures, in Peru, a country of 33 million inhabitants, 70 percent of people living in poverty were in urban areas in 2022.

And among the parts of the country with a poverty rate above 40 percent is Callao, a small, densely populated territory that is a province but has a special legal status on the central coast, bordered to the north and east by Lima, of which it forms part of its periphery.

The municipality of Ventanilla is known as a "dormitory town" because a large part of the population works in Lima or in the provincial capital, also called Callao. Because of the distance to their jobs, residents spend up to five or six hours a day commuting to and from work, so they basically only sleep in their homes on workdays, and very few hours at that.

Guillén says it is necessary to bring visibility to the workload of women and the fact that it is not valued, especially in poor outlying urban areas like Callao.

"We need a long-term policy immediately that guarantees equal education for girls and boys, and gives a boost to vocations, without gender distinctions, that are typically associated with women because they are focused on care," says the expert.

She adds that if more equality is achieved, democracy and progress will be bolstered. "This way we will be able to take better care of ourselves as families, as society and as nature, which is our big house," she remarks.

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues