In Bali, a Pivotal Moment for Climate Postponed

UNITED NATIONS, Feb 21 (IPS) - Facing a crucial meeting this week in Bali, the board of the U.N.'s Green Climate Fund (GCF) once again postponed drawing out the bulk of policy that will guide the fund as it prepares to open later in 2014.

Facing a yawning funding gap, the 24-member board said it would "aim for" splitting the financing it doles out 50:50 between mitigation and adaptation efforts and to devote at least half of adaptation monies to vulnerable regions. In a minor victory, members also clarified language over a mechanism for countries to seek redress with the fund.3

The GCF, formally established in 2010, is intended to serve as the primary vehicle for industrialised countries to pay for mitigation and adaptation in the developing world. Almost immediately after its creation, though, wealthy countries began backtracking on their original commitments and started pushing for a greater use of private funds to leverage their smaller contributions.

A paucity of pledges in Bali and a statement indicating the board would "maximize engagement with the private sector" bolstered concerns over the potential for a slow unraveling of donor promises and a watering down of what began as a clear-cut way of repaying developing countries for damages caused by carbon emissions.

"The GCF Board urgently needs to decide on the shape of the Fund, but progress is grindingly slow," Oscar Reyes, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, told IPS from Bali. "Most of what was scheduled for decision in Bali has been postponed. Given the inability to decide on matters of substance, the chances of significant breakthroughs at the next Board meeting in May look extremely slim."

That next board meeting will take place May 18-21 in Songdo, South Korea.

Aletter signed by 80 civil society organisations called for ensuring the fund "truly prioritizes and meets the needs of climate-impacted people in developing countries, free of undue business and industry influence."

Credit: http://wattsupwiththat.files.wordpress.com/

Credit: http://wattsupwiththat.files.wordpress.com/

"Climate finance is compensation, reparations paid by those countries most responsible for the climate crisis to those worst impacted," said Sarah-Jayne Clifton, director of Jubilee Debt Campaign, a signee of the letter.

"It must be adequate and predictable and from public sources, and fully accountable to the developing countries who need it, not the profit-driven multinational companies of the rich world and their financial backers."

After an original promise of 100 billion dollars was made at the 2009 U.N. Climate Summit in Copenhagen, climate financing dried up as governments facing austerity budgets at home chose to deprioritise it. The Overseas Development Institute estimates multilateral climate financing pledges fell by 71 percent in 2013.

When delegates met in Warsaw last November for the most recent U.N. Climate Summit, rich countries balked at a decreased 70-billion-dollar pledge.

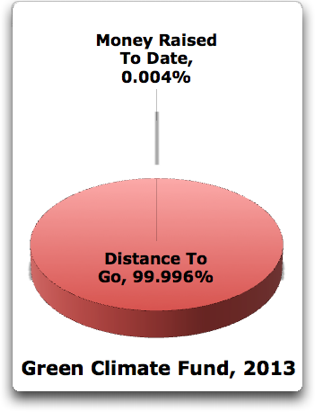

It was hoped that the Feb. 19-21 meeting in Bali would clarify from where and exactly how the fund's coffers will be filled. Prior to the meeting, the GCF had received 34 million dollars from Germany and South Korea, just enough to pay the staff at its Incheon headquarters.

Without clarification and donor guarantees, the U.N.'s 2015 comprehensive global climate conference in Paris could be thrown into disarray.

Attendees said they would have been happy with pledges of 10-20 billion dollars in Bali but donors offered up less than one million, just over a quarter of it in a highly symbolic donation from its host, Indonesia.

Though complete abandonment of the fund is a long way off, the slide towards private funding is causing concern among even the most cynical of observers.

"The vast body of that money should be from developed country's budgets," said Reyes. "It needs to be made political priority."

The fund was initially intended to avoid replicating climate financing schemes already attempted by multilateral lenders and development banks – lenders who expect the return of at least their principal amount. Unlike those institutions, the GCF was meant not merely to achieve economic stabilisation in poorer countries or repair damage after storms. Instead, its genesis included the moral spirit of reparations for historic wrongs.

Yet like many international climate agreements, time has loosened memories and dampened initial euphoria.

"Our concern is that it doesn't become ‘the World Bank for Climate Change' and that it actually focuses on projects that can't be done by private investors alone," Reyes told IPS. "But what we see in particular is the Secretariat is heavily staffed by people from the developed world where there is this tendency of seeing investment only as what can be leveraged from the private sector."

Reyes says the 50:50 funding split should be binding and not aspirational. Money earmarked for mitigation in middle-income countries could potentially end up funding cleaner fossil fuel projects like natural gas installations. There had been hope that the board would emerge from Bali with stronger language limiting how much, if any, of funds could be spent on fossil fuels.

Severe flooding is one of many devastating effects of climate change, as the Caribbean island nation Dominica experienced in 2011. Credit: Desmond Brown/IPS

Severe flooding is one of many devastating effects of climate change, as the Caribbean island nation Dominica experienced in 2011. Credit: Desmond Brown/IPS

Representation

In Bali, civil society groups called into question representation at the meetings, which they say gave the business sector and in particular large corporations too much influence.

Under the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, non-governmental constituencies are split into nine groupings, only one of which is the business community. That the Bali meetings had only two active observers – one from the business community and one from civil society representing the other eight, including trade unions, farmers and indigenous groups – fueled those accusations.

"The corporate capture of the Green Climate Fund is deeply troubling and yet another example of the interests of private finance and multinational corporations being placed above the public interest," Clifton told IPS.

A central unresolved point of contention concerns how much of the fund should be dedicated to grants and how much of it to loans, as well as how generous those loans should be.

"One of the issues that should be decided here are the terms and conditions of concessional lending," said Reyes. "The terms that we were pushing for would be around not contributing to indebtedness –we think adaptation should be grant funding."

In the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan - even as its delegates engaged in a hunger strike at the Warsaw summit – the Philippines government immediately took out one billion dollars in emergency loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Though both institutions provided smaller direct grants, the model troubles groups that have for years campaigned for debt forgiveness in the developing world only to see climate change potentially push those regions towards further loans.

"Climate finance should not be profit-driven, nor forced as loans or other debt-creating instruments on to countries already burdened by both the worst impacts of the unfolding climate crisis and the obligation to service existing unjust, illegitimate debt," said Clifton.

Like moths to a flame, countries with large financial sectors like Switzerland and the UK have reportedly been talking up the benefits of sophisticated currency swaps as ways to safeguard private foreign investment. While such assurances will be required for certain outlays, groups are concerned that money being pledged does not become a pool for Wall Street to play in. In Bali they had hoped to set limits on the private sector's involvement – that did not happen.

But Wall Street may end up footing much of the bill itself. Growing pressure in Europe has seen moves to use income generated by proposed Financial Transaction Taxes – levies on the buying and selling of assets – to fill gaps in climate financing.

© Inter Press Service (2014) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues